Nuovo Cinema Paradiso film review by Giuseppe Tornatore: an Analysis of the Film’s Themes and its International Reception

Introduction

Nuovo Cinema Paradiso (also known as Cinema Paradiso) is a 1988 film, directed by Giuseppe Tornatore, which charts the life of Salvatore Di Vita, known as Toto, and his love of cinema. It was first released in 1988 in Italy at 155-minutes in length—after a poor box office performance in Italy, it was later cut down to 124 minutes and distributed internationally. There are multiple versions of the film—the two initial versions as well as a special 173-minute director’s cut. This paper will describe the plot of the film, followed by some of the main themes—which ultimately led to the film’s initial failure in Italy and subsequent success abroad. The reception of the film (both domestically

and overseas) will be discussed, along with details of its international distribution deals and awards.

In 2002, Tornatore released a director’s cut of the film (with additional scenes which had been cut to make the film more appealing)—this will also be discussed in relation to editorial choices and why the shorter version performed better internationally.

Background and Themes

Cinema Paradiso portrays Toto Di Vita’s life in a Sicilian village (Giancaldo)—he is obsessed with movies and makes efforts to befriend Alfredo, the local projectionist. Alfredo also serves as a father figure and mentor for Toto. When the village theatre burns down, Alfredo is blinded and Toto takes over his job in a new version of the Cinema Paradiso venue. As a teenager, Toto falls in love with Elena but when she is sent to Palermo, Alfredo convinces Toto to leave Giancaldo forever to reach his full potential in Rome. The film begins in present-day Rome—Toto’s mother calls and asks him to return for Alfredo’s funeral. The story unfolds through Toto’s flashbacks to his youth. Cinema Paradiso explores many universal themes such as nostalgia, youth, dreams, loss and reflections on the past.

Tornatore made Nuovo Cinema Paradiso in Giancaldo (the Sicilian village where he grew up) and like Toto, he was inspired by the movies he watched as a child. At the time when Cinema Paradiso was released, the movie industry was undergoing changes with many viewers choosing to watch videos rather attend cinema screenings. Nuovo Cinema Paradiso explores these changes in cinema history from the times when an entire village would delight about the projection of any film to the modern era where the rise of television and video eclipsed the movie theatre. The film portrays the decline of societal collectiveness through the changes in how films were consumed (Hope, 2005).

Through long sequences portraying movie-theatre screenings, Tornatore focuses on the simple pleasures of watching movies with other people. He portrays the character who recites all of the lines, a priest secretly indulging in infectious music and a sleeping viewer—along with those who playfully try to wake him up. The old movie segments which punctuate Cinema Paradiso are significant as they inspired Tornatore in his own childhood and because they brought entire villages together in the theatre which became a place of worship and fraternising Cardullo, 1990). Some critics described these classic-film references as arbitrary but it can be argued that his method served as a mimesis of the way in which locals in Giancaldo experienced movies (Marcus, 2002). Tornatore may also have been playing with emotional contagion—audiences tend to connect and react strongly to characters when the camera lingers on their facial expressions for longer than needed to express information (Hope, 2005). As such, these theatre scenes show how deeply-immersed Italian audiences were with movies in the 1940s and 1950s and this in turn is a clever way to engage viewers of Nuovo Cinema Paradiso. Towards the end of the film, Toto and locals from Giancaldo (who seem to have hardly aged) witness the demolition of the Cinema Paradiso building—this is a melodramatic statement about the death of collectiveness in the Italian cinema world.

Nostalgia is one of the primary themes of the film—Tornatore examines how holding on to the past can prevent a person from moving on (particularly in Toto’s love life). Toto’s present-day existence in Rome is portrayed as cold—he lacks true love and does not seem to have a sense of community.

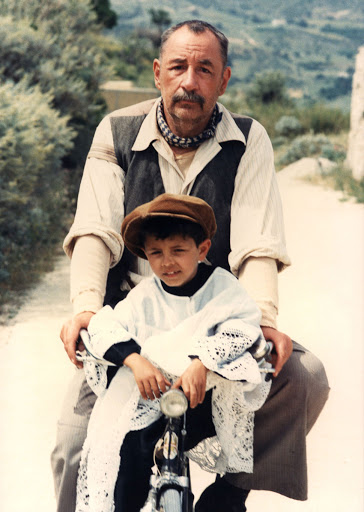

In contrast to this, Toto’s flashbacks of warm memories are presented much like idealised movies scenes. The cinematographer captures his youth in soft, hazy summer lighting, particularly in the scene where Alfredo carries Toto in his bicycle basket (Hope, 2005). When teenage Toto films Elena on the streets, she is portrayed in diffused light and almost appears angelic. Apart from the aesthetics, the treatment of certain scenes is light-hearted—even harsh moments such as a teacher beating a fellow-student are treated (and remembered) with a comic and nostalgic tone.

Romance, memory and storytelling are prominent in the film—when young Toto is missing Elena, he asks for a thunderstorm and his wish is granted. Elena suddenly appears—the couple then kiss in the rain in a scene which mimics the melodramatic style of romantic movies (Hope, 2005). This can be read as sentimental or a playful imitation of the love scenes which the local priest had censored. The film explores the ways in which we tell stories—when Toto wants to win Elena’s love, Alfredo advises him by recounting a story about a soldier who woos a princess. When Toto asks what happened at the end—Alfredo says that there is no ending and he has no idea what the story means.

Alfredo’s story lacks a conclusion and this is prophetic of Toto’s unfulfilled and unresolved love with Elena (Cardullo, 1990).

Reception in Italy and abroad: Distribution and Awards

As mentioned above, the film was shortened to 124 minutes due to its lack of success upon initial release in Italy. Cinema Paradiso presents Italy’s decreasing interest in going to the cinema—similarly, the film failed to attract a large audience in Tornatore’s home country. Harvey Weinstein stepped in (working with Miramax) and reduced the director’s 155-minute version to 124 minutes.

Miramax held the US and worldwide distribution rights and Palace handled the UK market. The success of the film following the release of the shorter version somehow justifies the editorial cuts made by Miramax (Patterson, 2013). Cinema Paradiso was received well internationally as a celebration of the power of cinema and many other relatable coming-of-age themes. It won the Special Jury Prize at the 1989 Cannes Film festival and went on to win an Oscar in 1990 for the Best Foreign Film.

Nuovo Cinema Paradiso was received with mixed feelings in Italy—critics who did not care much for the film said that it played up to American stereotypes of provincial characters in an antiquated version of Italy (Ferrero Regis, 2009). Nostalgia as a theme was at the root of the film’s failure and subsequent success—for many Italians, this sentimentality was trite and primitive; however, international audiences found the movie charming and emotional. Audiences in Italy were more interested in watching American movies—Tornatore said that Cinema Paradiso was removed a few days after its initial release to make room for Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Haberman, 1990). Literary critic Fredric Jameson pointed out that Nuovo Cinema Paradiso featured ‘nostalgic post-modernism’—where the idealised use of images from the past are used to compensate for modernism’s lack of history (Degli-Esposti, C, 1998). This focus on provincial Italy was outdated and did not appeal to Italian audiences who had a thirst for modern themes.

Speaking about the film’s initial reception in Italy, Tornatore said that critics there dismissed him as too young to represent the 1940s and 1950s—furthermore, they were cynical about the sentimentality of the film, scorning the fact that audiences were left in tears (Haberman, 1990). The film first received recognition at Cannes—perhaps it took a foreign audience to appreciate the sentimentality of the film without criticising its authenticity. Foreign audiences do not have the same reactions to films as locals as they are less concerned with the way national identity is portrayed. The French film Amélie received similar criticism in France—many French viewers found it too nostalgic, oldfashioned, romantic, and clichéd (Durham, 2008). Once Nuovo Cinema Paradiso was re-released in Italy (and after it received awards from abroad) it performed much better in the box office. Tornatore highlighted that this is common in Italy—films such as Fellini’s The White Sheikh and Rossellini’s Open City underperformed in Italy until they received recognition abroad (ibid.). After winning awards in many prominent European and American festivals, Italians began to appreciate Cinema Paradiso as a celebration of cinema. Furthermore, it triggered the revival of Italian cinema and provided potential for future collaborations with international distributors (Ferrero Regis, 2009).

The changes made by Weinstein and Miramax were carried out to increase the profitability and success of the film. Furthermore, Miramax spent a lot of money on marketing to make the film an international success and it had better connections with the Oscars committee (MacDonald, 2009). As such, it may not have been the case that Italians rejected Cinema Paradiso—they just did not put such resources towards marketing a film by a young director. In a 1990 article in the New York Times, Tornatore recalled that the combination of lukewarm reviews with a weak marketing campaign hampered the film’s initial box-office success: “we don’t do very well in advertising our movies, except for the two or three that feature beloved Italian comics” (Haberman, 1990).

Cinema Paradiso: the New Version

To redress the butchered version of Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, Tornatore released a 173-minute director’s cut of the film in 2002. The longer cut of the film includes a chance encounter between Toto and Elena, 30 years after their last meeting. This version provides a sense of closure to their story.

Fans of the film were excited to watch these additional scenes; however, film critics such as Roger Ebert said it was excessively long (Patterson, 2013). Had the film not been reduced in length by Miramax, it would not have had such a fan base to celebrate the director’s extended cut. Tornatore could see value in both versions—in an interview translated from Italian, he said: “I think that the long version, with all of its ingenious editing, has more the form of an epic romance, which, behind its playful and melancholy feel, cannot hide its tragic heart. The 125-minute version is closer to a novel, is more reassuring and manages to make the finale more strongly cathartic” (Desowitz, 2002). Alfredo is more of a multi-layered character in the longer version—in one scene, he advises Elena to forget about Toto—to allow him to realise his full potential. While Alfredo encourages Toto, he also obstructs his biggest love. In a sense, the shorter version appeals more to American sensibilities as Alfredo is portrayed as pure, kind and well-meaning—and the audience can feel reassured that Toto became a success. However, European cinema has a tendency to be more multidimensional and ambivalent. Some of Tornatone’s subsequent films were not as well-received in America as audiences there came to expect bittersweet and nostalgic themes (Bullaro, 2010).

Conclusion

Sometimes it takes an outsider’s vision to really allow a film reach its creative potential – Miramax understood that audiences would be more engaged if the film was shorter. The shorter cut also managed to convey Toto’s relationships with Elena and Toto in a satisfying way – the modern-day -reunion scenes were superfluous as the audience can easily imagine what became of Elena. Furthermore, international audiences love to see Alfredo in a purely positive light. Although it initially underperformed in Italy, Nuovo Cinema Paradiso was received well internationally as a celebration of the power of cinema. As Hope (2005, p.76) put it, “Nuovo Cinema Paradiso encourages a global awareness of cinema as a shared cultural patrimony that continues to enrich the present”.

Peachy Essay essay services provides a wide range of writing help including book and film reviews.