According to the World Health Organization (W.H.O.), a team is defined as “Two or more people working interdependently towards a common goal.” The W.H.O. elaborates that “Getting a group of people together does not make a ‘team.’ A team develops products that are the result of the team’s collective effort and involves synergy. Synergy is the property where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts (Salas, Kumar, Sepúlveda & Villanueva, 2007, p. 2).

From the abovementioned we may note key identifying differences between a team and a group. A team is a state of mind, that is a commonality, shared aims among all its members; members of a team do not work dependently or independently, but interdependently, mutually supporting and their interests and risk closely overlapping. A team is rooted in the concept that two or more people collaborating tend to produce or create more than the sum total of their individual efforts.

On-line resources of the Pennsylvania State University (P.S.U.), as citing Katzenbach & Smith (1993) define a team somewhat more managerially as ” … a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they are mutually accountable.”

Couprie (n.d., p. 2, as citing Dyer [1977]) states that “A team is defined as a collection of people who rely on group collaboration such that each of its members experiences an optimum of success level reaching of both personal and team based goals.”

Thus, the importance of the synergy element in the logic of a team is clear by now; Couprie (n.d.) espouses not only that people reach a collective maximum when working together instead of apart, but also that a team member can fulfill their full potential as individuals, better on a team than on their own.

Daren Wride, writer and motivational speaker, makes out four “facets” to a team’s successful characteristics: “diversity, unity through trust, trust due to a challenge” and “attempting something big enough that it calls for … [the team’s] best” (Wride, n.d., para. 3). Wride supports diversity as a team building strategy because ” … while it may be easier working with people like us, they tend to have the same perspectives, weaknesses, and blind spots. The result, like an inbred species, is a weaker organization” (Wride, n.d., para. 5). For example, “A team of purely analytical, task oriented types will forget that we’re all in the people business; a team of relational, unstructured types might be too busy partying to complete the job” (Wride, n.d., para. 6). Wride distinguishes trust as perhaps the most important factor that binds a group of people together to make them in to a team (at least when practically oriented). Wride (n.d., para. 12) concludes by defining a team as ” … a diverse group of people united by trust, and by a challenge that calls for their best.”

Thus we see that a team, unlike a group of people that is traditionally cohesive and peaceable, should deliberately include members whose personalities are very different; not because this encourages dramatics, but because the team is practically oriented (toward the attainment of a goal), and while every team member has strengths and weaknesses, the totality of the team may have a repertoire of strengths that are well distributed, representing a “jack of all trades” personality.

Under Wride’s logic, many groups of people may in fact be described as teams, as they may be very different from one another, yet live or work together trustingly and harmoniously to attain an end that they all believe in. Couprie (n.d., p. 2, citing Dyer [1977]) explains that “They [teams] exist everywhere in society. At work, there may be several different work groups (requirements, quality assurance, testing). Each one is a team. Project teams consist of people from different groups brought together for a specific activity. A worker may be a member of more than one team at work. Even the family is considered a team … Team dynamics run through the family in the same way as at work.” Later on, Couprie (n.d., p. 2) explain that we mistakenly do not think of these groups of people as teams because teams tend to be considered in a more organizational or formalistic sense and because it is assumed that teams must be successful.

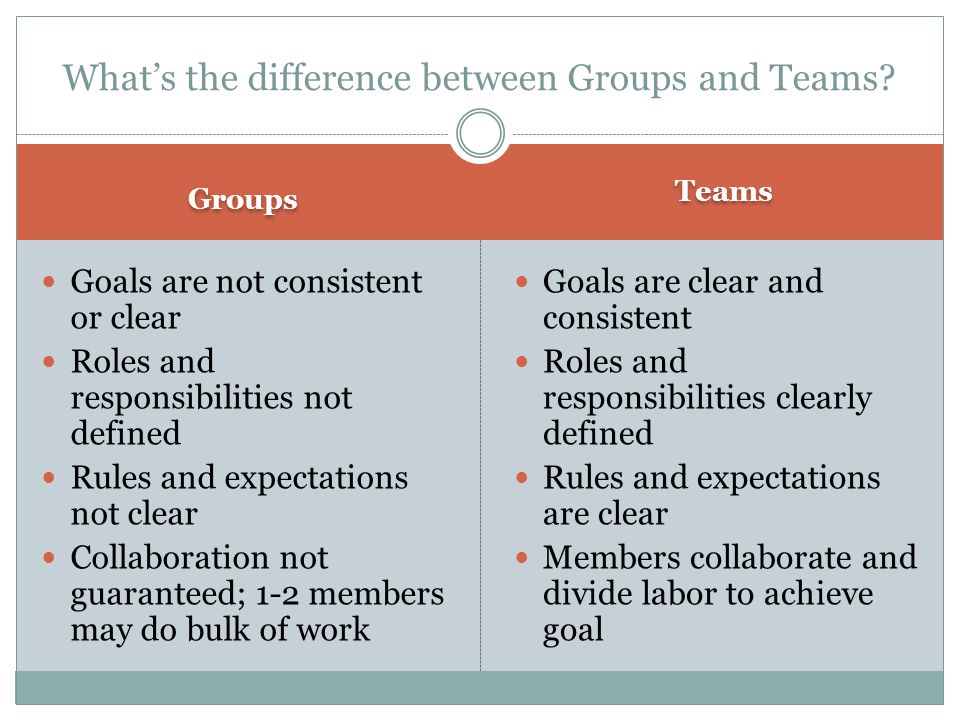

Deborah Mackin, who founded and presides over New Directions Consulting, Inc., and has written books on team management, asks, ” … when does a group become a team? What are the distinguishing characteristics of a team that are different from a group?” (Mackin, n.d., para. 2). She presents a well constructed answer: a team should be manageably small, consisting of no more than a dozen people, or it will become cumbersome and uncoordinated; teams should reflect diversity; teams must be democratically inclined, instead of centralized; team members are united by belief in shared responsibility. She defines a group as ” … a small group of people with complementary skills and abilities who are committed to a leader’s goal and approach and are willing to be held accountable by the leader” (Mackin, n.d., para. 4). In her view, groups are more centralized, instead of delegated like teams; members of a group feel only individually responsible for their shares of the work, rather than collectively responsible for the success of the project; and the view of the leader is what goes, rather than all the views of the members, democratically. She concludes that teams are more effective and efficient than groups, but that they take more time and are harder to put together, so that organizations will use groups to execute small tasks, but will build teams when dealing with important projects.