Abstract

The construction industry significantly contributes to the economic growth of a country. Despite its contributions, it is highly criticized for being a major producer of waste. Construction waste imposes critical threats to the environment including pollution, depletion of natural resources, loss of biological diversity, etc. Therefore, the concept of SCWM has gained a wide momentum in recent years. Although SCWM is thoroughly investigated in the literature, there is a lack of a comprehensive view on the main differences in SCWM of developed and developing countries. Therefore, this research aims to assess the strategies, deficiencies and challenges of SCWM practices implemented in Malaysia and the UK seeking to provide recommendations to enhance future practices. The research is based on qualitative secondary research with a thematic analysis presenting the main themes and sub-themes identified. A comparison between SCWM of both countries is presented and major similarities and differences are identified. Based on such a comparison, the efficiency of both management systems are analysed and recommendations to enhance future performances are presented.

Glossary of Terms

- Building Research Establishment (BRE)

- Construction and demolition (C&D)

- Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB)

- Construction Industry Master Plan (CIMP)

- Construction Industry Transformation Programme (CITP)

- Construction Waste Management (CWM)

- Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR)

- End of Waste status (EoW)

- European Union (EU)

- Ministry of Housing and Local Government (MHLG)

- Municipal Solid Waste (MSW)

- The Solid Management and Public Cleansing Corporation (SWCorp)

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

The construction industry significantly contributes to the economic growth of a country. Its crucial role arises from the fact that it aids governments in enhancing standards of living and quality of life through the development of socio-economic projects such as housing, highways, schools, etc (Reza, Halog, and Ismail, 2017a). Despite its contributions, it is highly criticized for being a major source of pollution due to the massive amounts of waste generated by the industry (ISWA, 2015). The primary sources of waste, generated within the industry, are attributed to the core activities of construction, demolition, and renovation (ISWA, 2015).

Construction waste imposes critical threats upon many countries including developed countries (Raju and P, 2015). Firstly, the disposal of construction waste into landfills results in the emission of toxic gases and major air pollutants; thus, exacerbating the greenhouse effect (Raju and P, 2015). The negative impacts are also extended to affect water quality as well (Enshassi, Kochendoerfer, and Rizq, 2014). Secondly, the improper management of construction waste often leads to the depletion of natural resources (Enshassi, Kochendoerfer, and Rizq, 2014). Other impacts of construction waste include but are not limited to problems associated with poor health, loss of biological diversity, effects on the flora and fauna, noise pollution, and acid rain (Enshassi, Kochendoerfer, and Rizq, 2014).

The concept of waste management has been practised across the globe for a while. Nevertheless, the traditional approach to waste management was severely criticized for not integrating all the processes encompassed within the system (Seadon, 2010). Furthermore, it focused on short-term outcomes by opting for undemanding waste disposal strategies namely, burning, dumping and burying waste (Agarwal, 2016). Also, it targeted solid waste in general without giving particular attention to the needs of the different industries (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017)

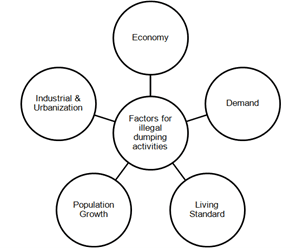

The efficient management of waste imposes several challenges in developing and developed countries (ISWA, 2015). However, such challenges are more severe in developing countries due to the lack of awareness, firm laws and regulations, the incorporation of advanced technologies and collaboration between different stakeholders (Amina, Shafiq and Amira, 2020). Malaysia has been suffering from high rates of waste. The following figure illustrates the main factors for waste generation including the demand for housing and commercial projects (Rahim et al., 2017).

Figure 1.1: Waste generation factors in Malaysia (Rahim et al., 2017).

On the other hand, developed countries struggle to achieve the desired outcomes in terms of the associated financial and environmental costs (ISWA, 2015). In the UK, the gathered data evidence that the largest proportion of the waste generated and disposed into landfills are C&D waste (Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs, 2013). Developed and developing nations, including the UK and Malaysia, have resorted to the enforcement of multiple laws and regulations to govern the waste management practices within their territories (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017).

For managing solid waste in general, Malaysia has launched two federal organisations namely, the National Solid Waste Management Department and the Solid Waste Management and Public Cleansing Corporation (SWCorp Malaysia). Similarly, the UK had adopted the EU Landfill Directive (1999/31/EC), the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC), the Waste and Emission Trading Act (2003), etc for managing its solid waste in general (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017).

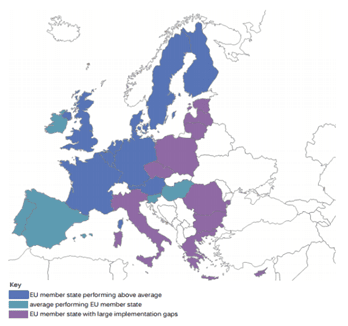

Enforced laws were strictly abided by mostly in developed countries. However, it was evident that many developing countries are reluctant to enforce strict legislation to regulate the disposal of waste (Slowey, 2018). Yet, they were not abided by if enforced (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017). Even when the laws are abided by, waste management practices are yet to be inefficient. The figure below reveals the performance of EU countries, most of which are developed nations, in managing waste. It is apparent that most of the EU countries are rated as average and below average in adopting and implementing effective waste management strategies (ISWA, 2015).

Figure 1.2 – Performance of EU countries with regards to waste management in 2014. Source (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016).

Consequently, the sole enforcement of legislation has proven to be inadequate to attain the desired extent of effectiveness for both developing and developed nations (Aminu, Shafiq and Amira, 2020). As a result, there has been a wide momentum to shift towards sustainable waste management (SWM) practices by both developed and developing nations (Reza, Halog, and Ismail, 2017a). SWM practices mitigate environmental impacts and positively affect the economic status of a country (Jay Aulston, 2010). Primarily, SWM strategies promote the reduction, reuse and recycling of waste (Yeheyis et al., 2012). Most recently, SWM practices focus on the prevention of generated waste from the early stages of design (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016).

1.2 Research Gap

From an extensive review of the literature, it is apparent that SCWM could incorporate distinct strategies and techniques in different countries resulting in varying efficiency rates and challenges encountered. This was particularly vivid while distinguishing between developing and developed countries due to the differences in resources, technologies and awareness levels. Yet, the literature lacks a comprehensive view that sheds light on such strategies and highlights the main differences between developed and developing countries when it comes to C&D waste management.

1.3 Research aims & objectives

Based on the aforementioned, this research aims to assess the strategies, deficiencies and challenges of CWM practices implemented in Malaysia as a developing country and the UK as a developed country seeking to provide recommendations to enhance C&D waste management.

The rationale for choosing the UK is that it is a leading nation towards the implementation of sustainable waste management strategies (ISWA, 2015). On the other hand, the rationale for choosing Malaysia for comparison is that it is a developing country and is among the countries with the highest generations of construction waste annually. Also, Malaysia is well-known for its illegal disposal practices that are adopted by many of its contractors (Nagapan et al., 2012a; Rahim et al., 2017); hence, comparing the practices of Malaysian and UK companies will aid in understanding the various aspects that contribute to effective waste management in both developing and developed nations.

Thus, the research objectives are as follows.

- To compare the adopted waste management strategies in the UK and Malaysia.

- To highlight areas of deficiencies & challenges encountered by both countries.

- To provide critical analysis of the effectiveness of waste management practices of both countries.

- To draw conclusions and recommendations that would enhance C&D waste management.

1.4 Research Significance

This research builds on the existing literature by identifying the strategies, deficiencies and challenges of both developed and developing countries in managing C&D waste. The recommendations presented in this study would aid governments and stakeholders in different countries to have enhanced strategic planning towards SCWM. Through such a comparison, countries could choose the right course of action, mitigate faults and risks, and anticipate the consequences of their action plans to be better acquainted to achieve their desired outcomes.

1.5 Research Methodology

This research utilises secondary data for achieving its aim and objectives. Therefore, the research heavily depends on desk research of qualitative data from online governmental reports, organisational websites and peer-reviewed journals to gather data about SCWM in the UK and Malaysia. Thus in conducting this, three research phases were conducted namely, identification of research gap, development of a database and the analysis. After the literature review, a systematic mapping approach was adopted for the development of the database. The third phase entailed a thematic analysis of the gathered database where data are identified and aggregated based on main themes and sub-themes. Hence, a descriptive analysis was conducted followed by the comparative and exploratory analysis. Subsequently, insights on the efficiency of each SCWM system along with conclusions and recommendations are withdrawn.

1.6 Research Outline

This research is divided into 6 main chapters and follows the following outline. Chapter 1 presents an introduction to the topic along with the main aims and objectives. Chapter 2 is an extensive review of the literature; Chapter 3 provides an overview of the methodology used; chapter 4 discusses the results obtained with regards to the aforementioned objectives. Finally, chapter 5 presents a discussion of the findings followed by chapter 6 which outlines the main conclusions and recommendations.

1.7 Chapter summary

The construction industry is associated with the generation of massive amounts of waste. The waste management strategies within the industry have evolved over the years and are different in different countries. This research aims to identify and compare the SCWM practices adopted by the UK and Malaysia to fill the existing gap in the literature and provide a baseline for governments and practitioners within other countries.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

The generation of massive amounts of waste due to industrialisation, population and economic growth has been an issue that raised multiple concerns throughout the past few decades (Jay Aulston, 2010). Since then, many initiatives have been undertaken to effectively manage waste and mitigate the negative impacts associated with inefficient waste disposal practices giving rise to the waste management concept (Amasuomo and Baird, 2016). Waste management practices have undergone several evolutions to enhance the outcomes of the process. Most recently, there has been a shift and increasing momentum towards sustainable waste management strategies. Therefore, this chapter highlights the concepts of waste and waste management in general and in the construction industry.

2.2 Waste- Types & Sources

2.2.1 Waste- Definition & History

Waste, as described by the EU’s Directive 2008/98/EC Article 3(1), is any substance or object that is discarded. The increase in the amount of waste generated is due to the increase in urbanisation and industrialisation rates (Amasuomo and Baird, 2016; Jay Aulston, 2010). The five major sources with the greatest contribution to waste generation, nowadays, are Commercial Waste, Municipal Solid Waste (MSW), Industrial Waste, Agricultural Solid Waste and Construction Waste (Amasuomo and Baird, 2016).

2.2.2 Waste in the Construction industry

Waste generated within the construction industry is often referred to as C&D waste (Raju and P, 2015). C&D waste is defined as “waste produced by demolition and building activities, including road and rail construction and maintenance and excavation of land associated with construction activities (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 201, p.3). C&D waste is generated in every phase of any project (Raju and P, 2015); It consists of reinforced and non-reinforced concrete, bricks, masonry with cement and mortar, metals, bituminous substances, timber, glass, plastic, paper (Raju and P, 2015), ceramic, cardboard, gypsum, asphalt, shingles (Slowey, 2018), soil, sand, fines, rock and excavated stone, asbestos, etc (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011).

2.2.3 C&D Waste Statistics

A report published by the International Solid Waste Association (ISWA) in partnership with the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) revealed that the global waste generated from the construction industry amounts to 36%, on average, of all wastes produced annually.

Figure 2.1- Data for global waste generation by industry. Source (ISWA, 2015).

In the US, almost 29% of the waste disposed of in landfills every year is from construction and building activities (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017). In other countries such as Brazil and Canada, the annual C&D production percentages are, on average, 40%, and 27% respectively (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017). In Australia, 44% of the annual waste generation is from C&D activities (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011). In the European Union (EU), approximately, 25%-30% of all the waste generated annually is from C&D (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011). In 2018, the total amount of C&D waste generated in Europe was 336.73 million tonnes. Germany, France and the UK were responsible for the generation of the largest amounts of C&D waste with the generation of 90.97, 72.11 and 55.42 million tonnes of C&D waste respectively (Eurostat, 2018).

2.3 Waste management

The concept of waste management emerged several decades ago with the advancement in technology and the dawn of industrialisation (Amasuomo and Baird, 2016). With such an increase, the negative impacts of waste had been recognized widely creating an urge for the efficient management of waste.

2.3.1 Flaws of the traditional waste management systems

The traditional processes of waste management incorporated the handling, storage, transportation, treatment and disposal of waste to eliminate the negative consequences on public health and the environment. The early approach to managing waste was based on the three main aspects namely, waste generation, collection and disposal (Seadon, 2010; Jay Aulston, 2010). The waste disposal techniques were primarily focused on disposals through burning, storing or burying the generated waste (Agarwal, 2016).

2.3.1.1 The focus on the physical components of the system

The traditional waste management approaches were rigorously criticised for the following reasons. Firstly, traditional waste management strategies lacked a comprehensive planning approach as they treated each of the three aforementioned phases independently (Seadon, 2010). Nevertheless, it was soon apparent that waste is generated within a system that includes several interdependent units working simultaneously to achieve the desired outcome (Seadon, 2010); therefore, the separation of the physical components of the system from the conceptual components such as the society and the environment in waste management had proved to be ineffective (Seadon, 2010).

2.3.1.2 Solutions that focused on short-term outcomes

Secondly, the analysis of the gathered data was targeting the development of solutions that did not focus on solving the root cause of the issue but rather, focused on short-term outcomes without giving regards to the associated impacts in the long run (Seadon, 2010). Burning waste was the easiest and most rapid approach to managing waste; however, the procedure was associated with several negative impacts (Agarwal, 2016). With regards to storing waste, the first approach was the disposal of waste into dumps and impoundments which were later replaced by sanitary landfills (Seadon, 2010; Agarwal, 2016).

The developed countries have resorted to landfills in the 1970s (Seadon, 2010; Agarwal, 2016).

Apart from the negative impacts of landfills on the environment, the dependency on landfills created severe shortages as the majority were soon over-capacitated in many countries (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016). Subsequently, such countries were unable to cope with the increasing rates of waste (Seadon, 2010; Agarwal, 2016). Although landfills are widely used to date, many countries have resorted to incineration which is a process that utilises advanced technologies to recover energy from the burned material (Agarwal, 2016). However, incineration plants are often criticised for being capital intensive with low rates of return on investments (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016).

2.3.1.3 The targeting of all types of waste by early legislation

Due to these flaws, there was a shift towards the enforcement of legislation and regulatory measures to govern the waste management approaches (Jay Aulston, 2010). However, early legislation and regulations have focused on managing all types of waste without considering particular industries (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017). To illustrate, the EU had introduced the Landfill Directive (1999/31/EC) with the objectives of having percentages of non-biodegradable solid waste generated from all industries for 2010, 2013, and 2020 as 75%, 50%, and 35% respectively (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017). Moreover, another Directive was the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC) which developed the principle of polluter-pays. The principle is based on the idea that polluters or waste holders, regardless of the industry, are liable for all the costs associated with the pollution attributed to their practices and disposals (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017).

Regarding the Landfill Directive (1999/31/EC), it was adopted by the UK subsequent to the introduction of the Waste and Emission Trading Act (2003) and in England following the introduction of the waste strategy of 2007 (Ajayi & Oyedele, 2017). In Malaysia, early legislation had the same issue of targeting all industries simultaneously. The Local Government Act that was developed in 1976 has introduced legislation prohibiting the disposal of wastes in any stream, channel, river, or drain. It had assigned specific dumping areas for waste as one of the initiatives for waste management (Abu Eusuf, Ibrahim and Islam, 2012).

2.3.2 The shift towards sustainable waste management practices

The early regulative measures have proven to be inefficient; theus, there is an increasing demand for developing SWM systems and SCWM plans (ISWA, 2015). The shift to SWM approaches gained recognition in 2014 when the European Commission had declared advocacy for promoting resource efficiency and waste minimisation programs (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016). The figure below shows the main targets of the EU Commission to be achieved by 2030 (ISWA, 2015).

Figure 2.2- Targets of the EU commission for sustainable waste management. Source (ISWA, 2015).

2.3.3 The 3R approach

The three main pillars of SWM are “Reduce”, “Reuse” and “Recycle” which are also referred to as the “3R approach” (Rexa, Halog, and Ismail, 2017a). The 3R principles are derived from the hierarchy of minimising waste to ensure that waste, including construction waste, is effectively managed (Reza, Halog, and Ismail, 2017a). The figure below reveals the hierarchy of the prioritisation of waste management practices.

Figure 2.3: Waste Management Hierarchy. Source (Reza, Halog, and Ismail, 2017a).

Among the three main components of SWM, recycling has gained considerable attention due to its benefits (ISWA, 2015). These include but are not limited to reductions in the amount of waste disposed of into landfills, saving energy, conserving natural resources, and reducing green gas emissions (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016). In addition, recycling is associated with economic benefits (ISWA, 2015). To illustrate, the recycling of C&D waste had become a business opportunity for the private sector (Jay Aulston, 2010). The following table represents a few of the materials that could be recycled from C&D waste (Jay Aulston, 2010).

Table 2.1- Materials that could be recycled from C&D waste. Source (Jay Aulston, 2010).

2.3.4 Characteristics of SCWM systems

A report published by Transparency Market Research (2018) reveals that the forecasted generation of C&D waste will increase up to 2.2 billion tonnes in 2025 (Slowey, 2018) creating an urge for effective SWM systems. As stated by Halkos and Natalia Petrou (2016), “Sustainable waste management requires the combination of skills and knowledge of physical sciences and engineering together with economics, ecology, human behaviour, entrepreneurship and good governance” (p.1). SWM practices should interact and adapt according to the changes in their external and internal environment (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016). Hence, it should be function-oriented rather than product-oriented to account for the fact that products change; thus, their recycling and reusing strategies will change as well (Seadon, 2010).

An SCWM system should be characterized by being flexible; it should incorporate a futuristic approach that embeds long term thinking (Seadon, 2010). Moreover, SWM should seek perfection through the incorporation of feedback from stakeholders to take corrective actions that would assist in achieving the desired goals (Seadon, 2010). The most recent approach for SWM further builds on the 3R approach by prioritising the prevention of waste generation in the first place. This could be achieved in the early stages of a project through re-thinking and re-designing approaches (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016).

Figure 2.4- Sustainable waste management hierarchy. Source (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016).

2.4 Background & History of Construction Waste Management

2.4.1 Europe’s legislation to C&D waste management

Construction waste management (CWD), as a concept, emerged after World War II in Germany when waste generated due to the high demolition rates were managed (Jay Aulston, 2010). Subsequently, many developed countries have encouraged the development of C&D waste management plans (Yeheyis et al., 2012). On the other hand, developing countries are reluctant to enforce such legislation due to many reasons including economic, technical, financial, and logistics constraints (Nagapan et al., 2012a; Rahim et al., 2017). Initially, the major approach adopted by developing countries was the discouragement of disposals into landfills. This was regulated by imposing high taxes and penalties (Yeheyis et al., 2012).

On a country level, Germany had introduced “The Commercial Wastes Ordinance” and “The Waste Wood Ordinance” Acts which were enacted in 2003 in an attempt to regulate the segregation, recycling and reusing of C&D waste as a source of energy (Jay Aulston, 2010). New Zealand enacted the Waste Minimisation Act in 2008 with an aim to reduce the amount of waste generated and disposed of (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011). In Denmark, the Dutch government had imposed taxes on the disposal of C&D waste in landfills since 1988 which were seven times higher in 2010 (Jay Aulston, 2010). France, Sweden and Denmark enforced aggregate levy on the use of aggregate from virgin quarries within their territories (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011). In the Netherlands, “The Chain Oriented Waste” Policy was enacted by the government within its National waste management plan set for 2009-2021 with C&D waste as its primary focus. The policy governs the procurements, grants and incentives in the area of C&D waste management, taxes imposed on disposals, and the polluter-pays instruments (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011).

Besides the enforcement of legislation, several guidelines were published by many countries to aid practitioners in managing C&D waste (Jay Aulston, 2010). To illustrate, Austria had established a guideline that sets the concentration limits of any pollutants in the recycled materials (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011). In Belgium, the government had published a tool that illustrates the environmental performance of all materials used within the construction industry to promote certain building materials with better environmental performances to clients (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011). The UK has a wider set of guidelines and specifications that aid in promoting the efficient management of C&D waste. These include “The specifications for highway works” and the “Design manual for roads and bridges” (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011).

2.4.2 Construction Waste management in the UK

The UK has been encountering challenges in managing its construction waste for several decades (Building Research Establishment, 2003). The roots of effective management of construction waste date back to the late 1990s. Landfill taxes were introduced in 1996 to discourage firms from using the landfill and promote recycling (DETR, 2000). Initially, the tax rates set were significantly low but they subsequently increased to be more effective in reducing the amounts of waste generated by the industry. The UK further imposed a levy in 2002 on the use of virgin quarries to obtain aggregates that are used within the construction industry (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011).

The “Strategy for Sustainable Construction” was developed in June 2008 and it involved both the government and the construction industry with a key goal of promoting the practice of sustainable construction. One of the main objectives of the strategy was to reduce the waste to landfill by 50% in 2012 compared to that generated in 2008 (Oyedele et al., 2013). Besides, it pressured the construction industry to develop its resource-efficiency programs to achieve zero disposals from construction waste into landfills by 2020 (Osmani, 2012).

Site Waste Management Plans (SWMPs) have been the main driver for reducing C&D waste to landfill in England since their introduction in 2008. They were voluntary in Wales, Scotland, and Ireland (Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd, 2011). The aim of the SWMP is to ensure that building materials are managed efficiently, waste is disposed of legally, and material recycling, reuse and recovery is maximised. Local authorities and the UK Environment Agency (EA) have the power to enforce the application of SWMPs through penalties or prosecution.

2.4.3 Construction Waste Management in Malaysia

The severity of C&D waste became more apparent in Malaysia recently with the increase in construction projects. The Construction Industry Master Plan (2006-2015) was launched in 2006 to improve the practices of the construction industry. It aimed to enhance the quality of health, safety, and environmental and work practices of the industry. In addition, several actions were also taken by the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) to further aid in achieving the plan’s targets. For instance, it developed guidelines for Construction Waste management. However, the CIDB outcome had not yet been translated into formal legal enforcements (Saadi, Ismail, and Alias, 2016). As a result, initiatives implemented by the government are not practised leading to contractors applying their own initiatives regarding construction waste management (Kafi et al., 2014).

Based on a study conducted by Jalil (2010), the gap between the governmental and practised initiatives was due to a lack of strict enforcing strategies, poor implementation techniques, and uncertainties regarding the role and responsibilities of the authorities in charge. Although landfilling is the most popular way of managing waste, it is considered the least favourable as Malaysia’s landfill areas are reaching their design capacity due to an increase in waste generation. Besides, providing new landfills was not a feasible option (Rahim et al., 2017). As a result, several entities have resorted to illegal dumping in Malaysia.

2.4.4 Chapter Summary

This chapter highlighted the waste and the waste management concepts along with the evolution patterns that took place within the construction industry up to the shift to SCWM strategies. In doing so, several strategies and legislations that were enforced by the EU are highlighted. Subsequently, the chapter gives an overview of the early CWM practices adopted by the UK and Malaysia.

3 Methodology

3.1 Introduction

The chapter highlights the methodology adopted by this research to attain its desired objectives. Hence, the chapter initially gives an insight into the existing research, data and data-analysis types. Subsequently, the adopted research methodology in terms of each of the aforementioned aspects will be stated along with the rationale for making the stated choice.

3.2 Research Types

3.2.1 Primary Research

Primary data is first-hand data that is gathered and owned by the researcher (Victor Ajayi, 2017). These are original real-time data that are collected to answer specific research questions at hand such as studying specific theoretical or scientific problems (Hox and Boeije, 2005). Such data is gathered through surveys, questionnaires, interviews, observations, focus groups and experiments (Victor Ajayi, 2017).

3.2.2 Secondary Research

Secondary data, on the other hand, is data that has been collected by others in the past. It is often gathered by researchers who are not part of the main study and is used to build on primary data through analysis and interpretations (Victor Ajayi, 2017).

3.2.3 Chosen Research Type

The research type opted for in this study is secondary research. The rationale for choosing this research type is the ability to obtain high quality data. This is because secondary research maintains a certain level of expert know-how and professionalism as compared to the data that would have been gathered by the researcher given the scope and the time limitations of the research. This is due to the fact that a wide set of data gathered by professionals and experts with extensive knowledge and expertise in the area will be collected. Also, it saves time and cost that is otherwise used for the analysis of the gathered data. Furthermore, due to the lack of standardisation in the CWMS, secondary research would facilitate having a comprehensive perspective on the mentality of the government and the industry as a whole rather than focusing on the practices and perspectives of certain companies or practitioners from whom the primary data would have been collected. Thus, allowing the researcher to have an enhanced judgment on the overall practices. Hence, data for this research are collected through a desk research of online sources. This research focused on online governmental reports, organisational websites and peer-reviewed journal papers only.

3.3 Data Types

3.3.1 Quantitative Data

Quantitative research is based on the positivist philosophy that argues that knowledge and truth are objective in nature (Ryan, 2018). Hence, it is based on reality that could either be proven or disproven and is obtained through measurements and observation. The philosophy also argues that knowledge should be value-free and should not be subject to any forms of bias from the researcher (Ryan, 2018).

3.3.2 Qualitative Data

Unlike quantitative data, qualitative data is based on the interpretivism philosophy which argues that knowledge and truth are subjective in nature (Ryan, 2018). Thus, a researcher using this approach is never far distanced from the results as his knowledge, understanding, rationale and intuition will be used to interpret the findings (Ryan, 2018). Subsequently, allowing the researcher to understand and have a grasp on the deeper meaning of the data analysed.

3.3.3 Chosen Data Type

The aim of this research is to review the CWMS in both countries namely the UK and Malaysia. Since there is no primary method or technique for managing C&D waste, this research utilises qualitative data to give a comprehensive overview of the C&D waste management practices in both countries to present factual information related to SCWM. Furthermore, the qualitative data describes the different attributes of the WMS of both countries such as the leadership styles, strategies implemented and perceptions of the industry with regards to sustainable CWM in both countries.

3.4 Research approach

The aim of this research is to identify and compare the SCWM strategies implemented in Malaysia and the UK along with the deficiencies of each system and the challenges encountered. The research is divided into three phases which are discussed here under.

3.4.1 Literature review

The first phase entailed a review of the literature to investigate the current state of SWM in the construction industry. The figure below illustrates the steps conducted in this phase.

Figure 3.1- Review of the current status of the literature & the research gap

3.4.2 Database

The second phase of the research included the identification of papers that would aid in bridging the existing gap in the literature. The research approach implemented is a systematic mapping to have a comprehensive overview while eliminating bias in the selection process. This mapping process included the screening, data extraction and data synthesis procedures (James et al., 2016). The phase started with the identification of papers based on the selected keywords which were chosen based on the primary review of the literature besides the aims and objectives of the research.

To identify the most effective keywords, a wide range of keywords were tested for their accuracy, relevancy and preciseness on ScienceDirect. The tested keywords included terms such as “sustainable C&D waste management” and “strategies of C&D waste management”. Thus, a filtering process was conducted to include the most relevant keywords. Papers were explored by typing the keywords “UK/United Kingdom/Malaysia” OR “construction” AND “demolition” AND “waste management” OR “recycling” OR “Construction waste” OR “C&D waste”. Research was done in four main databases which are ScienceDirect, Google scholar, EBSCO host and Wiley Online library. Besides, the relevant governmental websites of both countries were visited to gather governmental reports. The period of the past five years was chosen based on the primary review of the literature that indicated that the strong initiatives towards the shift to SCWM in both countries were apparent during this period. Upon conducting the literature survey, 714 papers were identified for both countries from all four databases. The following figure shows an example of the searching process. The same procedure has been applied to all other databases.

Figure 3.2:- Search process using the identified keywords.

3.4.2.1 Data screening

The screening process was conducted manually at two stages. The former stage entailed screening the titles, abstracts and introductions of the identified papers looking for keywords, aims & objectives of the papers and their findings to identify relevant papers. At this stage, the exclusion criteria excluded sources with publication year out of the past five years, with languages other than English, and non peer-reviewed papers. Also, the titles were screened and any duplications were detected and eliminated.

The results of the first screening process yielded 128 documents including those obtained from governmental archives. Consequently, the identified sources were manually screened to validate their applicability to this research by reviewing the full text. Papers that were addressing aspects that are not related to the strategies, deficiencies, challenges of SCWM sources are were not general to all countries within the UK were excluded. Hence, a database of 22 sources related to C&D waste management practices from the year 2015 to 2020 was developed.

Table 3.1: List of sources used in this research

3.4.2.2 Data extraction & synthesis

In this research, a thematic analysis was conducted. Thematic analysis is a technique that is widely used for the analysis of raw qualitative data to identify the necessary information and trends (Smith, 2020). Four major steps namely, data gathering, transformation, arrangement and analysis were done. The first step done was familiarisation where the investigator went over the gathered data to have an overall grisp of the basic themes. Thus, preliminary notes were taken and source prioritisation and organisation was done. The second step entailed categorisation of the identified sources. Analysis could be done through two methods which are the inductive and deductive methods. In the former method, the nature of the gathered data dictates the results of the research while in the latter includes having a predefined hypothesis against which the data is evaluated (Smith, 2020). In this research, data synthesis was conducted using the inductive method to identify the underlying themes of SCWM in both countries. Thus, data were aggregated under the following main themes and sub-themes before data analysis was conducted. It should be noted that themes overlapped between papers.

Figure 3.3: Main themes & sub-themes developed for the research

Figure 3.4- Development of research’s database.

3.5 Data Analysis

3.5.1 Descriptive Analysis

Descriptive analysis is an analysis technique that is used to describe and summarise the data gathered so that they end up making sensible patterns (Neo, 2020). It uses data aggregation and mining to describe data that is related to the past (Bachar, 2018) and answers questions related to “what happened” (Gibson, 2016).

3.5.2 Exploratory Analysis

The main goal of the exploratory analysis is to explore the gathered data by conducting a thorough analysis to identify relationships and connections among variables (Neo, 2020). Such type of analysis is used to formulate hypotheses and seek to verify their validity (Bachar, 2018). Therefore, this analysis technique entails the identification of patterns and anomalies (Neo, 2020).

3.5.3 Comparative Analysis

A comparative analysis is a form of analysis that explains differences and similarities between the aspects under investigation. Thus, comparative analysis involves the identification, examination, analysis, assessment, reflection, and criticism of a phenomenon to explain and offer a better understanding of all interrelated elements (Adiyia and Ashton, 2017).

3.5.4 Chosen Analysis Technique

This research utilises a combination of descriptive, exploratory and comparative analysis in examining the CWM practices of both the UK and Malaysia. Hence, the analysis of the data started with a descriptive analysis where the findings are outlined. Subsequently, a comparative analysis was conducted to compare the SCWM practices between both countries. Following the comparative analysis, an exploratory analysis was conducted to explore the reasons behind the identified strengths and weaknesses. Finally, based on the withdrawn conclusions, recommendations are provided to provide insights on areas that require further modifications and improvements.

3.6 Chapter summary

This study is based on secondary research where qualitative data was gathered on the SCWM practices of the UK and Malaysia. A total of 22 documents are identified from online sources after undergoing the screening process. Subsequently, a database was formed where data was aggregated and categorised based on a thematic analysis before they were analysed using a mix of descriptive, comparative, and exploratory analysis.

4 Results & Analysis

4.1 Introduction

There are several reasons for the continuous increase in the generation of construction waste. The following paragraphs present the results obtained with regards to the SCWM strategies of the UK and Malaysia along with the drawbacks and challenges associated with them.

4.2 Sustainable C&D Waste Management approaches.

4.2.1 Organisations involved in the SCWM

Within the SCWM of the UK, several organisations advocate and promote resource efficiency. These include the Green Construction Board, Construction Products Association, UK Contractors Group and Constructing Excellence, to name a few (Deloitte SA., 2016). While in Malaysia, the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) is the main organisation responsible for the general regulation of sustainability practices within the industry (Saadi, Ismail and Alias, 2016). Malaysia had also introduced the Centre of Excellence (CoE) to shift the construction industry into a sustainable industry and promote sustainable practices (CIDB, 2015a).

4.2.2 Main strategies

The UK had shifted towards the Circular Economy (CE) approach in compliance with the EU Circular Economy Action Plan (EEA, 2020). The CE approach is defined as follows “a reflection of introducing closed-loop systems in which integrating the maximum resources utilization in a way that put an extra premium on protecting the environment as well as shifting the mindsets towards turning the waste into wealth (Reza, Halog and Rigamonti, 2017a, p.220). The aim of such an approach is to achieve Zero Avoidable Waste (ZAW) in the construction industry. The figure below illustrates the UK’s transition to CE.

Similar to the UK, the 3R principles were adopted by the Malaysian government several years ago in an attempt to reduce, reuse and recycle C&D waste (Saadi, Ismail and Alias, 2016). However, this approach has not changed much to date as research has proven that Malaysia is still implementing the linear economy approach which consists of four main practices namely, Extract-Produce-Consume-Dispose (Reza, Halog and Rigamonti, 2017b).

4.3 Initiatives towards sustainable C&D Waste Management

In both the UK and Malaysia, the government combined several strategies, voluntary agreements, guidelines and new legislation to achieve the SCWM objectives.

4.3.1 Plans & Programmes

The UK government had launched several programmes besides the existing EU strategies such as The Waste Prevention Programme (GCB, 2020). To start with, the Resources & Waste strategy (2018), 25 Year Environment Plan, Making things last, and the Environment strategy are a few examples of strategies developed with the aim of eliminating avoidable waste from all industries by 2050. They endorse enhancing resource productivity, eliminating the generation of waste, encouraging and advancing resource management and recovery and also assisting different stakeholders in taking responsible actions towards waste management in general (GCB, 2020).

On the other hand, In 2015, a new programme called the Construction Industry Transformation Programme (CITP) was established in Malaysia as an extension to the CIMP (CIDB, 2015a). The CITP (2016-2020) was launched to ensure the persistence and consistency of the national agenda in meeting the 11 Malaysian Plan thrusts. Within the plan, the CITP developed Strategic Thrust No.2 (Environmental sustainability) to be able to attain a sustainable infrastructure which include facilitating the adoption of sustainable performance and reducing construction waste (CIDB, 2015b).

4.3.2 Construction methods & techniques

It is evident that the UK advocated for partnering and the incorporation of new procurement models in an attempt to enhance the performance of the industry along with eliminating the generation of waste (Sarhan, 2018). Also, there has been a strong momentum towards adopting the lean construction philosophy to enhance value and reduce waste (Sarhan, 2018). Besides, the UK had also launched the Construction Sector Deal, a form of partnership between the government and the construction industry, to enhance the status quo of technology used within the industry. Thus, it promotes innovating novel technologies to enhance off-site manufacturing and whole life performance of construction projects (GCB, 2020).

Malaysia, on the other hand, had introduced the Modular Coordination (MC) concept in 2003 and is still effective to date. Such a concept aids in standardising the designing and the choice of building components which assists in minimising C&D waste (Rahim et al., 2017). Also, Malaysia promotes the utilisation of the Industrialised Building System (IBS), a concept similar to the use of precast structural elements. It had set targets to achieve 70% and 50% IBS in the public and private sectors respectively by 2020 (CIDB, 2015b).

4.3.3 Guidelines

Concerning the voluntary agreements, the UK had developed several guidelines to be used by practitioners within the industry (Adjei, 2016). Waste management plans are an example of such voluntary guidelines and are developed through collaborations between the governmental entities of all member nations (Deloitte SA., 2016). Furthermore, voluntary Quality Protocol frameworks (QPF) were developed to provide guidelines on how waste could be processed to meet the requirements End of Waste (EoW) status (Deloitte SA., 2016). The Uk government has also developed 13 End-of-Waste Frameworks to guide different stakeholders on how to effectively manage C&D waste (GCB, 2020).

In Malaysia, the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) had launched the Guidelines on Construction Waste Management in 2008 to complement the master plan. Besides aiming to reduce the awareness of integrated waste management and waste minimisation, it also assists clients, contractors, and consultants in identifying means through which waste could be reduced. Thus, its objectives are to provide guidance, set roles and responsibilities, and list the legislative requirements to establish proper C&D waste management in Malaysia (CIDB, 2008).

4.3.4 Legislation

Legislation, in the UK, is enforced through the environmental protection entities and local councils of each member nation (Adjei, 2016). In line with its CE approach, the UK had introduced several amendments to the existing primary and secondary legislation under the name The Waste (Circular Economy) (Amendment) Regulations 2020. The amendments also include Part 2 which is Matters which must be included in waste management plans such as waste prevention measures, reuse and recycling policies, incentives, etc (Waste (Circular Economy) (Amendment) Regulations 2020).

Whereas, multiple legislation has been enacted in Malaysia to govern the management and disposal of solid waste. More specifically, The Pembinaan Malaysia Act 1994 (PMA) is governed by the CIDB of Malaysia. Although governed by a board that relates to the construction industry, the main focus of the Act is to reduce environmental pollution due to the deposition of waste. It also includes a Site Clearance Article that mandates the clearance of waste from the site location (Rahim et al., 2017). Another legislation is the Standard Specifications for Buildings Works (SBW) (2005) which is governed by the Ministry of Works (JRK, 2005). They outline the general duties of a contractor when it comes to major construction phases such as piling, excavation, concrete, and steelworks.

4.3.5 Assessment tools

The UK government is among the first countries to develop assessment tools. The BREEM scheme encourages designers, contractors and designers to meet the desired national targets of sustainability (Deloitte SA., 2016). However, no assessment tools were specifically developed for measuring the effectiveness of the implemented practices within the CE approach.

Similarly, Malaysia had introduced the Green Building Index (GBI) in 2009. The rating tool evaluates six main criteria namely, energy efficiency, management practices, material & resources, planning, indoor quality and water efficiency and innovation (CIDB, 2021). To aid in achieving the objectives of the CITP plan, The Ministry of Works through the Public Works Department (JKR) introduced the Malaysian Carbon Reduction and Environmental Sustainability Tool (MyCREST). This tool evaluates the sustainability rating of building projects using 11 assessment criteria that include Demolitions & Disposal Factors (DP) and Waste Management & Reduction (WM) (CIDB, 2015b).

Figure 4.2:- Assessment criteria of the (MyCREST) tool. Source (CIDB, 2015b).

4.4 Flaws & Deficiencies of the existing system

The following points highlight some of the flaws and deficiencies to the SCWM of both countries. It is worth noting that many of the UK’s challenges are also encountered by all the European countries due to the novelty of the CE approach.

4.4.1 Managerial issues

- In the UK, conflicts, due to the existence of multiple guidelines, arise due to the differences that exist within each guideline such as the definition of terms, and the classification of waste (GCB, 2020). The UK further lacks a clear strategy through which hazardous materials could be treated and recycled in the circular economy approach (EEA, 2020).

- Malaysia focuses on managing the generated waste instead of emphasising the prevention of C&D waste at the early stages of projects (Rahim et al., 2017). There is also a lack of decisive strategy and an overall policy that outlines the vision of the government and the industry when it comes to SCWM (Vasudevan, 2015; Yin, 2018). Malaysia has no proper allocation of resources for the planning of SCWM (Mei and Fujiwara, 2016).

4.4.2 Administrative issues

- The process of obtaining the required environmental permits is laborious in the UK. Although it has been revised to facilitate the process, medium-sized waste management facilities are still struggling to obtain such permits especially with aspects that are related to on-site recycling (Deloitte SA., 2016; Martos et al., 2019).

- Malaysia lacks compulsory enforcement of standards (CIDB, 2021; Aminu Umar, Shafiq and Amira Ahmad, 2020). Moreover, the SCWM practices are being implemented at a very slow pace from both the government and the industry (Vasudevan, 2015).

4.4.3 Technical/financial issues

- The UK currently lacks an effective standardisation technique that involves a wide range of materials, processes and products recycled by different recycling plants (EEA, 2020). Also, there is no construction-specific lists of waste along with the appropriate procedures to handle each (Sarhan, 2018)

- In Malaysia, there is a lack of key performance indicators (KPIs) against which the performance of contractors could be evaluated (Vasudevan, 2015). The system lacks an efficient data gathering and reporting strategy with regards to solid waste management in general; more specifically, data with regards to C&D waste is very limited (Reza, Halog and Rigamonti, 2017b). There is also a lack of some fundamental instruments, such as economic and legal instruments, that would aid the construction industry in reducing C&D waste generation and disposal (Aminu, Shafiq and Amira, 2020).

4.4.4 Infrastructural issues

- The UK has no appropriate infrastructure that facilitates the collection, segregation and recycling of C&D waste (Martos et al., 2019; GCB, 2020). The recycling industry, with relation to C&D waste, is still considered as immature and could not sustain the tremendous amount of waste generated from the industry (Osmani, 2015). Currently, there is a lack of waste infrastructure in many rural areas which in return leads to a surge in transportation costs to the recycling facilities in urban areas or across borders (Deloitte SA., 2016). In addition, there are not enough off-site manufacturers who could meet a wide range of demands for different construction projects (GCB, 2020).

- Malaysia lacks the required infrastructure and technologies that aid in the proper conduction of all the waste management processes starting from collection upto recycling/reusing C&D waste (Rahim et al., 2017). Existing landfills in Malaysia lack proper standards and no suitable treatment facilities to the dumped waste (Nagapan et al., 2012b; Reza, Halog and Rigamonti, 2017a)

4.5 Challenges to sustainable C&D waste management

The main obstacles to SCWM encountered by the governments, contractors, and waste management facilities are listed below.

4.5.1 Technical/financial challenges

- The UK is encountering challenges to identify the sources of waste that are avoidable. Moreover, there are difficulties encountered in the classification of some C&D waste as hazardous or non-hazardous waste which restricts the recycling process (GCB, 2020). Besides, several technological developments, that are capital and resource-intensive, are required within all sectors of the industry to implement the CE approach. Also, efficient data gathering, recording and communication systems should be developed where C&D waste is tracked (GCB, 2020).

- On the other hand, major challenges arise from the lack of experience, technical knowledge, and the required finances with regards to SCWM in Malaysia (CIDB, 2021). The private sector encounters several financial constraints which are the main barriers to the adoption of SCWM practices (CIDB, 2015b).

4.5.2 Managerial challenges

- The consequences of the CE approach is associated with several uncertainties. There is a high possibility that by reducing waste, more severe environmental impacts could be encountered; thus presenting a managerial challenge due to the extensive monitoring required (GCB, 2020). The government should search for the right incentives to promote the shift towards CE (Osmani, 2015).

- Malaysia needs to adopt effective and efficient planning of its construction projects (Ikau, Joseph and Tawie, 2016). The government’s initiatives are met by low levels of enthusiasm from contractors, clients, consultants and developers. A major cause for such reluctance is the lack of awareness (CIDB, 2015b) and the lack of financial incentives which might act as a critical barriers to the adoption of SCWM practices (Yin, 2018).

4.5.3 Implementation challenges

- The exhaustive segregation of C&D waste in the UK is challenging due to time, resources and space constraints on site (Osmani, 2015; Martos et al., 2019; GCB, 2020). Also, the poor quality of material streams generated from C&D waste makes it not suitable for reusing/recycling (EEA, 2020). It is anticipated that the commercialisation of secondary sources will impose more challenges within the UK (Martos et al., 2019) as there is an increasing concern about the prices of the recycled materials in comparison to their virgin alternatives (Osmani, 2015; EEA, 2020).

- In Malaysia, one of the main implementation challenges is that the benefits are assessed based on construction costs rather than life-cycle costs preventing the shift of the industry into more SCWM practices (CIDB, 2015a). Practitioners within the industry have reported other challenges including the low quality of waste generated, and the difficulty in managing time for recycling and reusing (Aminu, Shafiq and Amira, 2020).

Figure 4.3- Perspectives of Malaysian respondents on the challenges encountered during the recycling/reuse of C&D waste. Source (Aminu, Shafiq and Amira, 2020).

4.6 Comparison & analysis

4.6.1 General strategic approach

The results of this research revealed that the UK and Malaysia have entirely different strategic approaches when it comes to SCWM. From the definition presented by GCB (2020), it is also evident that the UK’s perspective values the generated waste as a resource that could be utilised. It is evident that the UK had undertaken a fundamental system re-design to prepare its construction industry for a radical change (Sarhan, 2018). Thus, the UK had bypassed the sustainability phase, what is also known as moving beyond sustainability (Wahl, 2018).

On the other hand, similar to other developing countries, Malaysia still follows a linear economy approach (Reza, Halog and Rigamonti, 2017a; Yin, 2018). Research on the mentality of the industry revealed that the extensive tendency to follow the linear approach emerges from the false notion of the abundance of resources where the purchase of raw materials at low costs is preferred as compared to investing time, finances, resources and effort on developing means to reuse and recycle waste (Reza, Halog and Rigamonti, 2017a). However, with the increase in the level of awareness, the globe is witnessing a wide momentum to shift beyond merely being sustainable (Wahl, 2018). Thus, it is vivid that Malaysia lags behind by not doing more than emphasising legislation to just reduce harm to the environment

4.6.2 Tools & Techniques

While both countries address two different approaches, the research revealed that the implemented tools and techniques to achieve the desired objects are quite similar. Both countries have relied on the development of strategies, guidelines, legislations and assessment tools towards an SCWM practice. The reliance on organisations to promote the notion was also evident in both countries.

However, the UK utilises such an approach to optimise the waste management process (Tam and Lu, 2016). This is done by putting a strong emphasis on the design, choice of materials, quality of waste produced and the elimination of the end-of-life of products (GCB, 2020). Nevertheless, it has been reported that designers have an insignificant role when it comes to managing waste in the UK as compared to contractors (Osmani, 2015). On the contrary, Malaysia focuses on managing the generated waste with little to no attention to how much waste could be prevented. This is evident from multiple studies that revealed that the recycling rate is 15%, which is much lower as compared to other countries such as EU countries (Reza, Halog and Rigamonti, 2017b).

4.6.3 Flaws & deficiencies

It is also evident that both countries lack the needed infrastructure to successfully implement their strategies (Aminu, Shafiq and Amira, 2020; GCB, 2020; Deloitte SA., 2016; Reza, Halog and Rigamonti, 2017b). Nagapan et al., (2012a) revealed that such lack mostly affected logistics aspects in Malaysia while the results of Aminu Umar, Shafiq and Amira Ahmad (2020) showed that such lack creates difficulty in sorting and transforming C&D waste. Similar to Malaysia, the UK practitioners highlighted that the major set back to recycling is logistics with the lack of suitable infrastructure and the high transportation costs (Ghaffar, Burman and Braimah, 2019).

It has also been reported that strict quality control measures limit the productivity of many small recycling businesses within the UK such as obtaining permits (Tam and Lu, 2016). As stated by an expert within the industry “The legislation in place has driven the industry towards better practice but the processes involved are sometimes overly bureaucratic to operate” (Ghaffar, Burman and Braimah, 2019, p.5). The following figure illustrates the major setbacks to recycling in the UK.

Figure 4.4: Major setbacks to recycling/ reuse in the construction industry within the UK. Source (Ghaffar, Burman and Braimah, 2019)

Malaysia also lacks firm planning, management, data recording and auditing of construction projects (Mei and Fujiwara, 2016; Yin, 2018). Appropriate planning is essential for the effective storage, transportation and procurement of resources which leads to a reduction in waste generation (Mei and Fujiwara, 2016). Thus, Malaysia’s weak management is the main reason for the increase in the waste generation (Kelishadi, 2012). A study conducted by Ikau, Joseph and Tawie, (2016) demonstrated that 37.6% and 36.3% of the participants stated that 60-80% of C&D waste is generated due to the inaccurate procurement and design practices within the industry (Ikau, Joseph and Tawie, 2016).

4.6.4 Challenges

With regards to the challenges, a major challenge ahead of Malaysia is the extreme lack of awareness of the importance of adopting SCWM practices. A crucial finding of a study by Reza, Halog and Rigamonti, (2017a) revealed that the majority of the respondents (59.9%), who were mainly practitioners within the industry, are unaware of the CE concept. Another study conducted by Aminu Umar, Shafiq and Amira Ahmad (2020), including 89 stakeholders, revealed that the majority of the respondents (44%) believed that only 10-20% of C&D waste could be recycled/reused.

Figure 4.5- Perspectives of Malaysian respondents on the percentages of C&D waste that could be recycled/reused. Source (Aminu, Shafiq and Amira, 2020).

In the UK, while it is apparent that stakeholders are aware of the significance of adopting SCWM practices (Adjei, 2016), there is a challenge to change the mind-set of stakeholders to accept CE practices (Sarhan, 2018). A study reported by Osmani (2015) revealed that the majority of the respondents, including contractors and architects, viewed that waste generation as inevitable. Furthermore, the challenge arises from the low market-readiness to adopt such practices due to technical and financial constraints (Ghaffar, Burman and Braimah, 2019). Besides the need to create innovative technologies, another challenge reported by the UK practitioners in the appropriate sharing and dissemination of the know-how (Adjei, 2016). Unfortunately, in reality, this might not be easily conducted as companies will tend to preserve their competitive advantage (Ghaffar, Burman and Braimah, 2019).

4.7 Chapter Summary

To summarise, the results revealed that the UK has shifted beyond sustainability by adopting the CE approach. On the other hand, Malaysia seems to be still struggling, despite its intensive initiatives, in enforcing an SCWM strategy. Both countries have several deficiencies and challenges ahead. Even though some of such deficiencies and challenges could appear similar, their extent and severity vary due to the different applications. The following table summarises the C&D waste management strategies of both countries.

Table 4.1:- Comparison of SCWM practices in the UK & Malaysia

5 Discussion

5.1 Introduction

After analysing the two SCWM systems and understanding the underpinning factors for successes and failures, a discussion of the efficiency of both management systems along with areas for improvement are presented in this chapter.

5.2 Efficiency of SCWM of both countries

From an extensive review, it was apparent that SCWM practices are efficient in the UK due to the effective leadership styles implemented by the government (Adjei, 2016). Effective auditing, reporting and gathering of reliable data and information are conducted precisely (Tam and Lu, 2016). Besides, the UK’s 40 different legislation are strictly enforced and abided by leading to significantly high resource recycling rates (up to 90%). However, the remaining 10% is currently being landfilled (Lou, Lee, Welfle and Abdullahi, 2021).

The preliminary evaluations of the CE approach indicated that it is an efficient system if accurately implemented. Firstly, the approach meets all the characteristics of an SCWM system that were identified in the literature. Thus, it embeds a futuristic vision (Seadon, 2010), combines sciences, engineering, entrepreneurship and good governance (Halkos and Natalia Petrou, 2016), and is flexible enough to adapt to changes (Slowey, 2018).

Meanwhile, SCWM is not yet efficient in Malaysia (Mei and Fujiwara, 2016; Yin, 2018). A study conducted by Reza, Halog and Rigamonti (2017a) revealed that the majority of the respondents (41.3%) rated C&D waste management as poor in Malaysia. To overcome financial constraints, there are several steps and initiatives that could be done with minimal costs as compared to the need of technological developments. To illustrate, to prevent the generation of waste, designers should be aware of the construction process to attempt to modify their designs (Nagapan et al., 2012b).

The case is quite similar when it comes to the efficacy of the enforced legislation in Malaysia. The CIDB acknowledges the fact as it aimed to heighten enforcement of the law in the latest strategy (CIDB, 2021). However, it is declared that Malaysia’s legislation is ineffective (Saadi, Ismail, and Alias, 2016; Yin, 2018). To illustrate, the SBW (2005) is silent regarding sustainable waste management practices such as recycling and reusing. Article 28.1.m of the SBW (2005) states that a contractor shall prepare “proper provision for the disposal of waste and refuse” (JRK, 2005, p. A/9); while Article 46.3 states “Garbage or construction waste shall be disposed of in a locally available landfill or hauled to disposal sites approved” (JRK, 2005, p. A15). No amendments to such regulations were conducted up to date.

5.3 Areas of Improvement

Regardless of the degree of efficacy of the implemented strategies, both the UK and Malaysia have several areas that require improvement. It is apparent that both countries do not provide enough incentives to encourage and motivate SWM practices. Within a study conducted by Ghaffar, Burman and Braimah (2019), a technical director in the UK reported “There should be a greater reward for recycling, in demolition, it is key to a successful project and we typically recycle 90þ% of all the waste we generate” (p.4). In Malaysia, the lack of incentives is apparent from the low levels of recycling reported within the industry (Aminu Umar, Shafiq and Amira Ahmad, 2020).

Another crucial aspect that both countries need to adopt is the incorporation of such practices into contract clauses which is crucial to set the projects’ overall targets with regards to recycled & reused materials. While conducting interviews with experts within the UK, Ghaffar, Burman and Braimah (2019) reported that 85% of the respondents claimed that SCWM practices should be included in construction contracts where contractors are held liable for fulfilling these obligations. One of the interviewees claimed the following “Contracts could be used to re-enforce legislation and also set out own company targets. There should also be a requirement for contractors to provide evidence of compliance” (p.4). Another interviewee stated that several benefits would arise out of such inclusion as contractors would be enforced to innovate and invest in novel recycling techniques (Ghaffar, Burman and Braimah, 2019)

The integration of all stakeholders is also necessary to achieve the desired objectives. In the UK, most of the strategies are developed through strong collaborations between the government and the industry (Deloitte SA., 2016). According to the literature, such collaboration is crucial as it ensures obtaining constant feedback to take corrective actions to the existing systems (Seadon, 2010). However, other forms of collaborations between different stakeholders is necessary. Although such collaboration has been prompted in the UK since two decades after the release of the Latham and Egan reports, it is yet not practiced to its fullest potential (Martos et al., 2019). However, this was not evident in Malaysia. A study by Vasudevan (2015) revealed that there is an average consensus among stakeholders within the industry in Malaysia on the significance of incorporating developers, architects and engineers in the SCWM system.

Also, it was reported that both countries lack workshops to increase awareness and facilitate the share of information and knowledge. UK practitioners had reported that the CE concept lacks enough promotion from the government (Ghaffar, Burman and Braimah, 2019). Also, the majority of the respondents in the study by Osmani (2015) reported that they seek a self-study approach to learn about SCWM practices. Besides, they lack a clear best practice framework that could be followed by the industry. In another study conducted by Osmani (2015), 67% of the respondents claimed that they develop their own inhouse SCWM plan.

5.4 Chapter Summary

From the aforementioned discussion, it was apparent that the UK implements a futuristic approach by adopting the CE concept for managing its waste. On the other hand, Malaysia is still struggling to shift to the SCWM system due to the lack of awareness, weak leadership and policy apathy. Thus, it is still following a linear economy approach. The results also revealed that both countries utilise similar tools to achieve their desired outcomes. However, their effectiveness varies due to several other factors.

6 Conclusion

6.1 Introduction

From the aforementioned discussion, it is evident that every construction phase holds on possibilities for the generation of waste that imposes several threats to the environment. This research aimed to identify and compare the SCWM practices implemented by the UK and Malaysia along with the associated deficiencies and challenges. The following paragraphs will present the main findings of this research to reveal the differences between developing and developed countries with regards to the management of C&D waste.

6.2 Summary of the main findings

Generally, the results of this research revealed that strong leadership, strict enforcement of legislation, planning, and awareness are the most significant factors that impact the success of the adopted SCWM strategies. Therefore, the investigator concluded that the UK’s practices are more effective due to the firm implementation of the aforementioned factors. The following points highlight the major findings of this study.

- The main strategies adopted for the management of C&D waste

The UK has shifted beyond sustainability by adopting the Circular Economy (CE) approach which views waste as resources and emphasises its movement in a closed loop. On the contrary, Malaysia’s primary focus is to manage the generated waste instead of preventing its generation in the first place. Hence, it still follows a linear economy approach.

- The main flaws & deficiencies in the two management approaches

- A major deficiency within the Malaysian approach is its weak enforcement of legislation which renders all aforementioned efforts ineffective. Ironically, the UK’s strict enforcement of legislation also acted as a deficiency due to the overly complicated procedures enforced such as quality control measures and the required permits. Therefore, governmental entities should seek to facilitate the transition to SCWM practices to encourage stakeholders and be able to effectively meet the predetermined objectives.

- Other flaws revealed in the Malaysian system include the lack of the required infrastructure, technology, technical expertise and efficient data gathering and reporting systems that mainly arise out of financial and technical constraints; thus, Malaysia should direct its efforts towards less costly alternatives such as enhancing the design of construction projects.

- While the UK similarly lacks the required technology and infrastructure to achieve the objectives of the CE approach, such issues will not pertain due to the availability of financial capabilities. On the other hand, other flaws that are more significant include the lack of standardisation of recycling secondary resources, the lack of a strategy to manage hazardous waste and the conflicts that arise out of the existence of multiple guidelines. Therefore, the UK should focus on developing a unified guideline that standardizes the outcomes of all processes within the CE approach.

- The main challenges ahead of both countries

With regards to challenges, Malaysia is facing difficulties in promoting SCWM practices due to the lack of awareness; therefore, Malaysia should raise awareness on assessing the benefits based on life-cycle costs rather than short term costs of the construction activities. Conversely, the UK is facing challenges in promoting CE approaches due to low market-readiness levels. Thus, the UK should focus on promoting the benefits that would be realised due to the shift.

6.3 Contribution to knowledge

From the analysis of both management systems, a few areas that were not touched upon in the SCWM strategies of the UK and Malaysia were identified. Through the identification of such aspects, this paper contributes to the existing knowledge by highlighting areas with great potential for improvements; by adopting and rectifying these aspects, the governments and the industry of both countries could shortly notice extensive augmentation to the outcomes of their exerted efforts. These aspects are outlined below.

- Firstly, the results revealed that both systems lack an alluring incentive system to encourage stakeholders to comply with the predetermined objectives. Therefore, authorities should consider providing several means of incentives such as remunerations, tax reductions, recognition and honouring of the exerted efforts.

- Also, the results revealed that the construction industry of both countries does not incorporate SCWM requirements into construction contracts. However, it was evident that such inclusion would enforce contractors to innovate novel technologies to achieve the desired outcomes.

- Furthermore, since C&D waste is a global phenomenon, collaboration forms an integral part of the success of any adopted or implemented strategy. Thus, both countries should promote collaborations on different levels such as between different authorities within different countries, authorities and the industry, among the different stakeholders and through the engagement of the local community.

6.4 Limitations

- The research is purely based on the results of desk research that may not precisely capture the actual perceptions, attitudes and behaviours of the different stakeholders within the construction industry of both countries. However, to avoid this, the research aimed to incorporate the different opinions of stakeholders captured by other researchers through interviews and other means of data collection.

- The research is based on qualitative data illustrating what is being implemented in both countries with regards to SCWM. The lack of the gathering of quantitative data, such as having percentages, quantities or figures, that translates the findings into tangible numerical results is a limitation of this study.

6.5 Recommendations

- This research sheds light on the different techniques employed by both countries. However, it is recommended to conduct an in-depth comparison of other aspects such as the existing practices, and the role of the local community and the society as a whole in SCWM.

- The research focuses on having a comparison between a developing and a developed country across different continents. However, it is recognised such a comparison would be more fair and realistic conclusions if conducted between countries of the same continent or geographical location.

- Also, the investigator recommends repeating the study on a wider scale while including more countries in the comparison to have a comprehensive overview of the different strategies, challenges and deficiencies that exist across the globe.

- The research could be done using a quantitative assessment tool or framework that would provide more tangible and practical results.

8 Appendices

Appendix A- Programme of work

Appendix B- Project Logbook

| Task | Description | Estimated Hours | Due Date | Supervisor’s feedback | Status | Remarks & Questions |

| Topic | Identification of the research topic | 5 | 30th of Nov | 16/11/2020 | Complete | Discuss the choice of Malaysia |

| Interim report | 1st draft of the report | 45 | 30th of Nov | 26/11/2020 | Complete | Discuss the content & structure |

| Interim report | 2nd draft of the report | 12 | 30th of Nov | 29/11/2020 | Complete | Overall review |

| Interim report | Final draft | 5 | 30th of Nov | – | Pending | Get feedback |

| Extensive Literature Review | 1st draft | 30-40 | 1st of Jan | 14/12/2020 | Pending | |

| Extensive Literature Review | 2nd draft | 20 | 1st of Jan | 21/12/2020 | Pending | |

| Extensive Literature Review | Final draft | 3-5 | 1st of Jan | 1/1/2021 | Pending | |

| Comparison | 1st draft | 50-60 | 1st of Feb | 14/1/2021 | Pending | |

| Comparison | 2nd draft | 30 | 1st of Feb | 21/1/2021 | Pending | |

| Comparison | Final draft | 10 | 1st of Feb | 1/1/2021 | Pending | |

| Presentation | Final draft | 10 | 8th of Feb | – | Pending | |

| Results & Analysis | 1st draft | 40-50 | 1st of Mar | 14/2/2021 | Pending | |

| Results & Analysis | 2nd draft | 20-30 | 1st of Mar | 21/2/2021 | Pending | |

| Results & Analysis | Final draft | 10 | 1st of Mar | 1/3/2021 | Pending | |

| Final Report Conclusions, Abstract & formatting | 1st draft | 20-30 | 24th of March | 14/3/2021 | Pending | |

| Final Report | Final draft | 10-20 | 24th of March | – | Pending |