Do you know how many different sorts of characters there are in literature? If you enjoy reading fiction, especially short stories, and novels, or if you want to be a fiction writer, you should be familiar with certain fundamental character types.

A fascinating diversity of character types is at the heart of all great narratives. The primary characters should be three-dimensional and engaging; they should be the type of dynamic people with whom readers and watchers can spend days without becoming bored. Supporting characters, such as sidekicks, love interests, parental figures, villains, and anti-heroes, are just as essential.

What is a Character in Literature?

There are some qualities or components that must be included in every story. Any piece of literature would cease to make sense or serve a purpose without these qualities. Stories, for example, must have a storyline or events that occur. The character is also an important part of the tale. Any human, animal, or creature depicted in a literary work is referred to as a character. In literature, there are many different sorts of characters, each with its own growth and role.

Character Development

The level of growth and complexity of a character is referred to as character development. Some characters are well-developed from the outset. For example, knowing how a character moves and talks, what she thinks, who she hangs out with, and what sort of secrets she has makes her more complicated and developed.

Other characters change during the course of a tale, beginning one way and ending another due to what occurs to them. Alternatively, you may only see one aspect of a character for a long before discovering another, demonstrating the character’s complexity.

Character Types

Character types can be classified in three ways. One way is to use archetypes, general descriptions of the many sorts of characters that appear in human stories. Another method is to classify characters according to the role they perform throughout the tale. The third technique is to categorize characters according to their qualities, describing how they evolve or remain the same throughout a story.

Characters Based on Their Roles in Stories

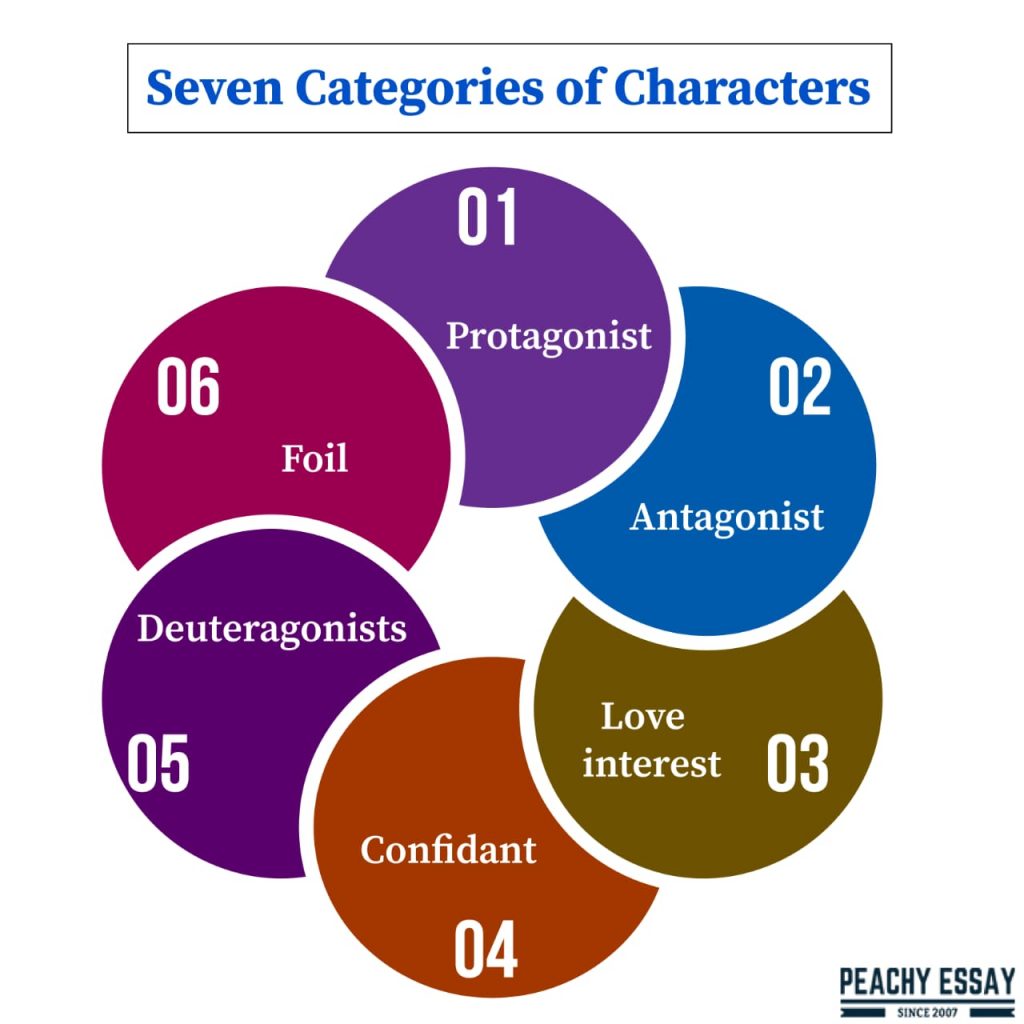

The protagonist, antagonist, love interest, confidant, deuteragonists, tertiary characters, and foil are the seven different categories of characters classified based on their function in a story.

Protagonist:

For most of us, the protagonist is a very recognizable concept: this is the main character, the big cheese, the show’s star. Most of the action revolves around them, and we’re supposed to care about them the most.

The protagonist is typically, but not always, the narrator in stories written in the first-person perspective.

The protagonist is the story’s primary character. They should have a logical backstory, personal motivation, and a character arc that follows them throughout the story. The protagonist is the figure with whom the audience has the strongest emotional attachment.

Antagonist:

If you’re an antagonist, you’re going to antagonize. You undercut, hinder, fight, or otherwise oppose one individual in particular: the protagonist.

The protagonist is almost always virtuous, whereas the antagonist is almost always wicked, and this is the cause of their struggle. This isn’t always the case, especially if the protagonist is an anti-hero with noble qualities and the adversary is an anti-villain with noble qualities. Even yet, the protagonist is usually the hero, and the adversary is the villain.

Love interest:

The protagonist’s love interest is the object of his or her desire. A fascinating and three-dimensional love interest is essential. In some form or another, romance appears in almost every narrative. There has to be some love interest involved, whether it’s the primary storyline, a subplot, or simply a blip on the narrative radar. This love interest is usually, but not always, a deuteragonist (hence why this separate category).

A love interest can be identified by the protagonist’s emotional reaction; however, this reaction can be varied. Some love interests make the protagonist swoon, while others make the protagonist sneer.

Confidant:

This character is the protagonist’s best buddy or sidekick, and the protagonist’s goal is typically achieved through the confidant—though not every narrative requires one.

A confidant is more difficult to find, especially because many novels center on the MC’s love affair to exclude other connections. On the other hand, the confidant may be one of the most important connections a protagonist has in a novel.

Confidants are frequently close friends, but they may also be prospective lovers or mentors. Even when the protagonist is hesitant to express their ideas and emotions with others, they do so with this individual.

On the other hand, the confidant may be someone the MC goes to not because they want to, but because they don’t have any other options.

Deuteragonists:

These personalities frequently cross paths with confidants. A deuteragonist is a character who is close to the protagonist but whose character development does not exactly match the story’s primary narrative.

A major protagonist and a secondary deuteragonist are common in most tales (or groups of deuteragonists). This is the figure that isn’t quite in the spotlight but is getting there.

The sidekick would be the deuteragonist’s comic book equivalent. They’re frequently seen with the protagonist, offering guidance, conspiring against their foes, and generally assisting them.

Their presence and close relationship with the protagonist provide warmth and heart to the tale, making it about more than simply the hero’s journey but also the friends they make along the way. Of course, not all secondary characters are pals — some are arch-enemies — but even the unfriendly deuteragonists add to the story’s richness.

Tertiary characters:

Tertiary characters occupy the story’s universe but aren’t always connected to the primary plot. These small characters can fulfill a variety of roles and have various levels of personal energy.

They appear in only one or two scenes throughout the novel, flitting in and out of the MC’s life.

A well-rounded narrative, however, still requires a few tertiaries. After all, we all have them in real life — the barista you only see once a week, the strange man in class — and any realistic fictional narrative should contain them as well.

Foil:

The purpose of a foil character is to bring the protagonist’s traits into greater perspective. This is because the foil is the polar opposite of the protagonist.

A foil is a character whose attitude and ideals are opposed to those of the protagonists. This conflict brings out the MC’s distinguishing characteristics, giving us a clearer image of who they are.

Even though they typically have an adversarial connection, the foil is seldom the main adversary. The MC and their foil may initially quarrel, but they gradually overcome their differences to become friends… or maybe more.

Character Types in Fiction

Examining how characters evolve (or don’t change) over the course of a tale is one method to categorize them. Character types include the dynamic character, the round character, the static character, the stock character, and the symbolic character, which are all categorized by character development.

Dynamic character:

A dynamic character evolves throughout the narrative. As a result, the finest protagonist is a dynamic figure. The protagonist of your tale and the majority of the deuteragonists should always be dynamic. To get your audience to notice the changes, you don’t have to make them very visible. These changes should occur organically and discreetly along your story’s journey.

Round character:

A round character, like a dynamic character, is a prominent figure that exhibits fluidity and the ability to shift from the time we meet them. On the other hand, some dynamic protagonists do not change until the events of the tale force them to.

A round character is comparable to a dynamic one in that they both evolve throughout the course of their story. The important distinction is that, even before any big changes, we as readers may deduce that the round character is complex and includes a wide range of emotions.

Static character:

Over the course of a tale, a static character does not alter much. Characters that perform tertiary roles in a story are sometimes referred to as flat characters. Many villains are also unchanging: they were bad yesterday, they’ll be bad today, and they’ll be bad tomorrow.

Stock character:

An archetypal figure having a fixed set of personality features is known as a stock character. Stock characters aren’t always flat, but you have to be careful while using them. Stock characters, like archetypes, are those well-known personalities who occur in stories repeatedly: the chosen one, the joker, the mentor. You don’t want to use them too often, but they may help flesh out your ensemble and make readers feel “at home” in your narrative.

The key to employing this personality type is to not rely solely on their archetypal characteristics. When creating a character, you can start with a standard image, but you’ll need to enhance and add other unique features to give them dimension.

Symbolic character:

A symbolic character is someone who reflects a broader notion or topic than themselves. They may be dynamic, but they also serve to direct an audience’s attention to larger themes discreetly. The majority of the characters are secondary; however, some stories include symbolic heroes.

Character Arche Types

Archetypes are sorts of characters that can be found in a work of literature. The following are some of the most often discussed.

The Lover:

The Lover is a romantic protagonist who is guided by his or her heart. Humanism, enthusiasm, and conviction are among their assets. Naivete and irrationality are two of their flaws.

The Hero:

The protagonist rises to the occasion to overcome adversity and rescues the day. Courage, persistence, and dignity are their strengths. Overconfidence and arrogance are two of their flaws.

The Magician:

A strong individual who has mastered the ways of the cosmos to accomplish their objectives. Omniscience, omnipotence, and discipline are among their strengths, but corruptibility is one of their faults.

The Outlaw:

The outcast refuses to conform to societal expectations. The outlaw may or may not be a terrible man. Independent thinking and skepticism are two of the outlaw’s qualities. Self-involvement and crime may be among their flaws.

The Adventurer:

A character’s inherent desire is to test limits and discover what’s next. Their strengths are that they are inquisitive, determined, and driven by the need to develop themselves. They’re weak because they’re restless, untrustworthy, and never content.

The Sage:

For those who inquire, a wise figure with wisdom. Wisdom, experience, and insight are among the sage’s assets. In terms of flaws, the sage can be too cautious and unwilling to join the action.

The Innocent:

A morally pure character, often a child, who’s only intentions are good. Their strengths range from morality to kindness to sincerity. Their weaknesses start with being vulnerable, naive, and minimally skilled.

The Creator:

During the story, the Creator is a driven visionary who produces art or architecture. Creativity, determination, and conviction are among their assets. Self-involvement, single-mindedness, and a lack of practical abilities are among their flaws.

The Ruler:

A person who has legal or emotional authority over others. Omnipotence, position, and resources are among the ruler’s advantages. Apathy, being despised by others, and continually appearing out of touch are some of their flaws.

The Caregiver:

A character who is always there for others and makes sacrifices for them. Honorable, unselfish, and devoted caretakers are just a few of their qualities. They lack personal drive and leadership, which are two of their flaws. They may even lack self-esteem.

The Everyman:

A likable figure who seems familiar with everyday life. They are grounded, down-to-earth, and relatable when it comes to strengths. In terms of flaws, they usually lack unique abilities and are generally unprepared for what lies ahead.

The Jester:

A purposefully amusing figure that provides not only comedic relief but also has the ability to express significant truths. The capacity to be humorous, disarming and perceptive are among his strengths. The ability to be annoying and shallow is one of her flaws.

A Guide for Using the 4 Main Characters in Literary Devices

The Protagonist:

A good protagonist has a desire for something (the tale objective) and goes out of their way to get it. In this job, we require someone proactive. Your tale will be ruined by a passive character. An excellent protagonist makes choices and takes action. These choices and behaviors have an impact on your story. According to John Gardner, “the single most prevalent mistake in novice fiction is failing to see that the major character must act, not merely be acted upon.”

The Antagonist:

They will face opposition on their way. The antagonist’s activities are generally the cause of this. This is the source of the plot’s conflict. Remember that conflict must have a resolution; therefore, your opponent must be as powerful as, if not more powerful than, your hero. This character must be credible. From their perspective, their motivation should be acceptable. This individual is the protagonist, while your protagonist is the antagonist in their narrative. (For further information, see Very Important Characters.)

The Confidant:

Along the journey, the protagonist will require assistance. Assist them in their journey by providing a confidante or a sidekick. This character is necessary so that your hero does not spend too much time alone contemplating things. The main character’s companion serves as a sounding board. ‘One of the most common mistakes that novice authors make is leaving their characters alone,’ says Chuck Palahniuk. It’s possible that when you’re writing, you’ll be alone. When you’re reading, you could be the only one in the room. Your character, on the other hand, should spend relatively little time alone. Because a lonely character begins to think, worry, or wonder.’

The Love Interest:

You should include a love interest in your protagonist’s life to make them more three-dimensional and complicate their existence. The protagonist’s strengths and, more crucially, flaws are shown through this character. Please keep in mind that the persona we choose for this device does not necessarily have a romantic love interest. It just has to be someone who can cause your hero to act erratically and unreliably. All of us are made idiots by love.

Why Are These Four Main Characters Important?

The primary characters, as literary devices, require us to show rather than tell. The protagonist’s relationship with the other three characters leads to concrete exchanges.

We must converse with and interact with these characters. If our deadliest adversaries are determined to locate us, we will not be able to avoid them. Unless we are willing to risk losing such friendships, we cannot disregard our best friends. If we are human, we cannot forsake the ones we care about the most.