Experiments are vital because they help us determine the relationship between various factors. They can be simple or complex depending on the number of variables you have. An example is determining the correlation between coffee or caffeine and sleep. When you want to undertake an experiment, planning is something you cannot afford to overlook. It would help if you considered several factors like ethics, measures of success, the variables. You need not worry because you are in the right hands. By the end of the guide, you will know how to design a great experiment.

What is an Experiment?

An experiment refers to the step-by-step procedure you take to investigate a particular hypothesis, prove an existing fact, or discover something. Most experiments happen in a laboratory because it is a controlled environment. However, do not limit yourself if you do not have access to one. The main types of experiments include:

-

Field experiment

The experiment can be a controlled or natural one and takes place outside a lab in the real world. An example would be observing the behavior of a lion in its natural habitat. In this kind of experiment, you sacrifice control. The results obtained are general, and it is common to combine a field experiment with a controlled experiment.

-

Natural experiment

In this experiment, you obtain data about your subject through observation. You have no control over the variables. A natural experiment is applicable where carrying out a controlled experiment is unethical or impractical, for example, weather occurrences. The experiment is mainly used in social science, epidemiology, psychology, and political science.

-

Controlled experiment

In most cases, it takes place in a laboratory. The important factors to consider here are control and manipulation. You make comparisons between a control group and an experimental group.

Assuming your hypothesis aims to prove that plants require water for germination, you put five similar seeds each in two containers. Then you place the containers in the same location. You proceed to water one container at a particular time every day for the set time. The container that is watered daily receives water treatment and is therefore known as the experimental group. The other container does not get any treatment and is therefore known as the control group.

Now that you know what an experiment is and the main types in existence, let us dive into the procedure of designing one.

Define your variables

Research questions are vital for an experiment and, most especially, for complex ones. That is because they make it easier to break down the big experiment into smaller manageable tasks. They also make it easier to stay focused on the end goal. Therefore come up with a few. They will make it easier to write down the variables for your investigation.

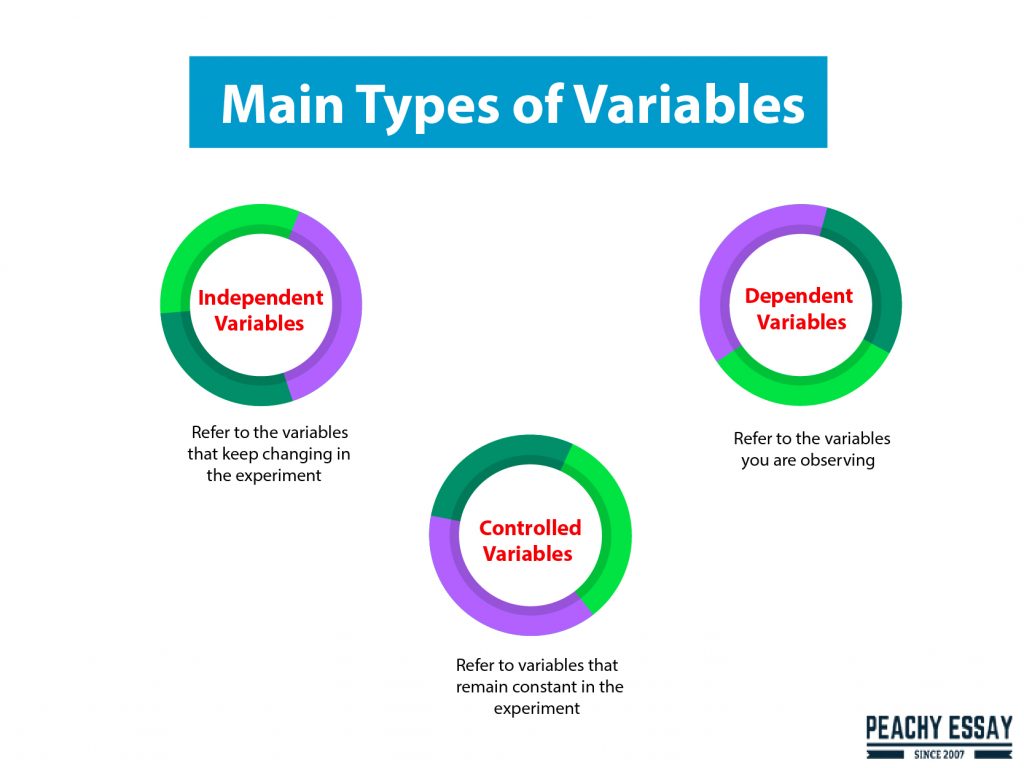

A variable, as the name suggests, is something that can change from time to time. It is vital to note that for an activity to count as an experiment, you must first come up with a prediction and then follow through with a specified procedure. There are three main types of variables: independent variables, dependent variables, and controlled variables.

Independent variables refer to the variables that keep changing in the experiment. It is the variable you control on purpose. You aim to see how manipulating it affects the dependent variable. The best practice is to have one such variable at a time. The more independent variables you have, the more complex your experiment becomes. In our germination example, water is our independent variable.

Dependent variables refer to the variables you are observing. Altering or manipulating independent variables is what helps you to observe their behavior. In the plant germination example, our dependent variable could be the time it takes for the seeds to germinate.

Controlled variables refer to variables that remain constant in the experiment. In the plant example mentioned above, the temperature, amount of sunlight, and the two containers that have the same size and contain the same amount of soil are controlled variables.

We also have extraneous variables. They are variables that you are not currently looking into but could interfere with the outcome of your experiment. They lead to inaccurate results where they are left uncontrolled. For our plant example, humidity is an example of an extraneous variable. A controlled environment will help you obtain more accurate results, especially where many external factors can affect your investigation.

After describing your variables, you need to come up with a hypothesis. The research questions are what will guide you in writing it. A hypothesis refers to a statement that describes a predicted result. Ensure that it is something testable.

Internal & external validity

They both show whether you can trust the conclusions of your experiment. In most cases, one comes at the expense of the other. You, however, want to ensure that they are both equally high. To do that, you can first experiment in a controlled environment to find out the causal connection and then, later on, carry out a field experiment to figure out if the previous results apply in the world.

Internal validity refers to the degree to which an experiment demonstrates a truthful cause and effect association between the outcome and treatment. It revolves around how you can conduct a study or research effectively. That means that you do not have differing explanations in regards to your findings.

A good example is if you provide therapy to a group of people, how certain are you that their improved performance results from the therapy?

Internal validity increases where there are fewer factors that can alter the outcome of the experiment. That also happens when you lack alternative conclusions of the research. That is, you do not have multiple explanations of the findings.

External validity depicts how relevant your results are in the real world. That is, can you apply your findings to other situations? How generalizable are your results? You can conduct a field experiment, conduct several experiments using varying samples, and apply calibration to improve external validity. Note that manipulating your independent variables influences external validity. Therefore be careful how you vary them.

The lack of external validity shows that the findings of the experiment only apply to the test subjects. For example, suppose you were working on designing the interface of a product. Therefore, the lack of external validity means that the interface does not apply to other people besides those in the experiment.

On the other hand, a lack of internal validity means that your results are invalid and that external validity is irrelevant.

Experimental & control conditions

You need to figure out the population of your study. Having many subjects means that you obtain more data. You then get statistical power through that.

At this stage, you divide the experiment into experimental groups and control groups. Control group refers to the group that does not receive any treatment. If you are testing the effect of less sleep on employees’ productivity in a company, the control group would consist of a group of people who sleep the recommended number of hours.

Experimental, on the other hand, is the group that receives treatment. In the illustration above, the experimental group would consist of employees who sleep fewer hours. The treatment in that scenario is the less number of hours the employees get.

Between- or within-subjects design

There are other groups that you have to classify your test subjects into:

Within-subjects versus between-subjects

In the between-subjects group, you apply a single level of treatment to the subjects. It is also known as classic ANOVA or independent measures design. The group has shorter sessions. That is because if they are too long, they become too boring or tiring to the participants. Setting up the experiment is also easier when you use this design.

For the within-subjects design, you ensure that you apply all the treatments to the subjects, although not simultaneously. You then measure all the responses. You apply the treatments at random instead of in a specific order to ensure that the order does not affect the expected results. The design includes fewer participants and is, therefore, less expensive.

Assuming we had two phone interfaces and we ensure that all participants interact with both phone interfaces, then that is an example of within-subjects. However, if we only allow the participants to interact only with one of the interfaces, that becomes between-subjects. Note that there has to be a participant for each interface.

Randomized block design versus completely randomized design

When it comes to the randomized block design, you first categorize all your subjects into blocks according to their characteristics. Then you assign treatments within the groups at random.

In the completely randomized design, you ensure that you randomly assign every one of your subjects to a treatment group.

Plan your measures

Measure refers to an item in the experiment that a participant responds to, such as interviews and a survey. Ensure that your questions are brief and easy to comprehend. Avoid ambiguous questions to ensure you obtain more information from the participants. Avoid using jargon from your field of study to ensure that even a layperson can respond easily to the questions.

Where you have two similar questions, ensure that you put them separately. That is because the participant may answer one and fail to respond to the other. That then leads to an inconsistent report. Avoid generalizing the questions.

Record the details of the experiment. For our plant germination example, you can measure a variable such as a temperature using a thermometer. Ensure the instruments you use are functioning adequately. That will ensure the accuracy of your records.

The final step involves analyzing your data.

Ethical considerations

When experimenting, especially one that involves other human beings playing the role of participants, there are some ethical factors to consider:

Consent

Ensure that you inform the participants of what you intend on doing. That means that you inform them of the risks or problems that may arise. Honesty here is mandatory. The participants, therefore, know what they agree to do. It is important to have written documentation.

Voluntary participation from the participants

Avoid using treachery or coercion to encourage people to participate in your experiments. Take only the participants who willingly want to participate. Note that the individual can choose to withdraw from the experiment at any time.

Potential of harm

That is practical in a field such as medicine. You have to ensure that there are minimal possibilities of harm befalling the participant. Ensure that the benefits outweigh the risk. For example, if your experiment involves asking participants to lift heavy things, ensure that you measure their strength and weight. That will ensure the participants do not sustain a physical injury.

The right to service

Some experiments do not warrant a control group. That mostly happens in the field of medicine. For example, if you want to observe a particular disease and how it affects the participants, you develop a treatment in between. It is your responsibility to provide the individual with the medicine. Otherwise, letting that person keep suffering for the sake of research is unethical.

Confidentiality

Most people prefer that the information they provide remain confidential and their identity anonymous. As the researcher, you need to avoid sharing the data you obtain with outside entities. In most cases, researchers usually do not know the identities of the participants.

Privacy

The participant determines when they are okay sharing data and to what extent. An invasion happens when you disclose information with third parties without consulting the participant. That is why the researcher must first inform the participant what the experiment entails before they begin.

Another form of invasion is when you study individuals without informing them what you are doing. That is a sensitive subject because it can affect relationships or associations once you disclose the data.

In conclusion, it is always wise to have a basic understanding of the test subject. For example, for the plant’s illustration above, have a rough idea of what germination is and what it entails. Otherwise, it becomes difficult to determine some factors, such as your independent and dependent variables.

Remember to be considerate and ethical.