In the social sciences, field reports are widely used. In addition, they provide information about the researcher’s observations regarding phenomena, processes, behaviors, and so forth. Sociological research is based upon theoretical reflections and conceptions, so it is impossible to observe without thinking about what is being examined. Nevertheless, theoretical concepts are not sufficient: one needs to prove their existence and even modify them according to their own observations.

In order to write scientific reports, the investigator must blend classroom concepts and assessments with observations and practices outside of the class. Field reports summarize observed persons, locations, or incidents, then analyze the information to find and classify major patterns linked to the study topic (s). The data is usually obtained through notes taken during the observation, although any method of data collection, such as pictures, sketches, and audio recordings, can be employed.

The Purpose of a Field Report

An analysis of observation data in the social sciences identifies and categorizes common themes around a specific research question that underlies the study. A field report describes how people, places, and events are observed. The scientist’s judgment of meaning is represented by data collected during an observation event or through observational procedures.

How do you Start a Field Report?

Field investigations are most typically assigned in practical social science courses. Field reports demonstrate a link between classroom theory and the practice of executing the task. A field report is also prevalent in other science areas [e.g., geology], but it is organized and planned differently than the one mentioned here.

Professors will urge students to submit a field report so that they can increase their grasp of essential theoretical ideas by carefully seeing and reflecting on people, locations, or occurrences in their natural environment. Field studies aid in the development of data gathering skills and the observation of how theories translate to the particular contexts, as well as the creation of data gathering strategies. In addition to providing evidence through observed professional practices that challenge existing theories or provide new insight, field reports provide an opportunity to gather evidence.

Everyone studies persons, their relationships, locations, and events; but, while producing a field report, your goal is to conduct studies depending on the evidence you collect through the design of a particular study, purposeful observations, synthesis of major results, and interpretations of their significance.

Observation Recording Techniques

Even though almost any form of data gathering technology may be used, the following are the most common:

Taking Notes

This is the most popular and straightforward way to keep track of your observations. Organize some shorthand symbols ahead of time so that documenting fundamental or recurring acts does not obstruct your capacity to watch, use numerous little paragraphs to indicate changes in activities, who is speaking, and so on. as well as providing room on the page for extra thoughts and ideas about what you’re seeing, any theoretical breakthroughs, and notes to yourself to be saved for later

Photographic Work

With the widespread use of digital phones, it is now feasible to take an almost endless number of high-quality photographs of the products, events, and people encountered while conducting field research. Images may be used to document a noteworthy moment in time and retain details about the environment where your observation takes place. When it comes to retaining the details of a site that might otherwise demand extensive note-writing, taking a photograph can save you time. However, keep in mind that flash photography might make it difficult to observe discreetly, so check the lighting at your observation spot; if it’s too dark, you might have to rely on taking notes.

Furthermore, rejecting the concept that pictures serve as a “window into the world” is preferable, as this assumption puts you at risk of misinterpreting what they depict. As with any data-gathering product, you, not the item, are the exclusive tool of assessment and meaning-making.

Recordings (both video and audio)

Recording your observations on video or audio has the advantage of providing you with an unfiltered record of the observation event. It also makes it easier to go through your observations again and again. This is especially useful when you obtain more information or gain new ideas during your investigation.

On the other hand, these tactics have the negative impact of making you more intrusive as an observer and will frequently be impractical or even illegal in some situations [e.g., a doctor-patient contact] and organizational contexts [e.g., a courtroom].

Drawings/Illustrations

This is not an aesthetic endeavor, but instead a practical need, such as making a map of the observation site or displaying items related to people’s actions. This could also take the form of scrawled spreadsheets, graphs, or diagrams displaying the size and number of actions seen. You may present this in a more understandable way while writing your field report. To save time, create a table on a separate page before such observations if you know you’ll be inputting data this way.

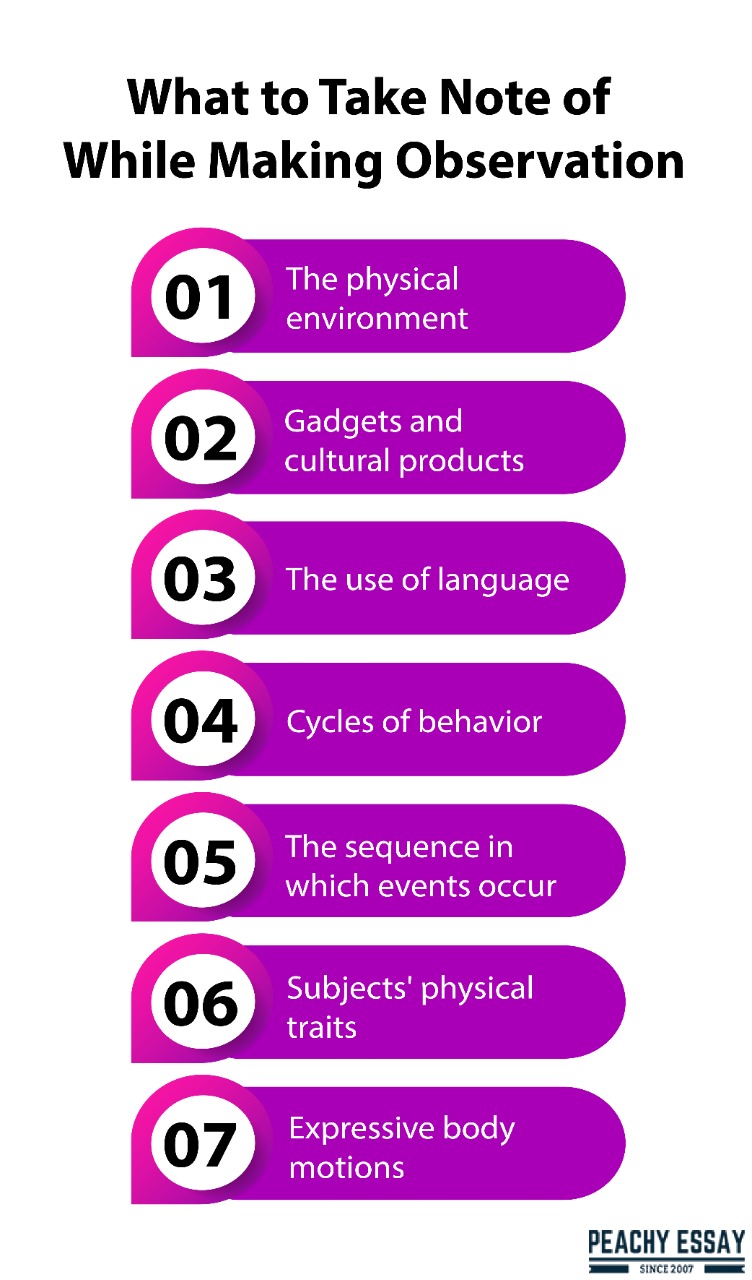

What to Take Note of While Viewing

Here are what to take note of while making the observation.

The physical environment

It entails the features of an inhabited area and how people utilize the location where the observation(s) are taking place.

Gadgets and cultural products

The presence, positioning, and arrangement of things that influence individuals’ behavior or activities are referred to as material culture. If available, describe the cultural artifacts that symbolize the persons you are observing’s views [i.e., their values, ideas, attitudes, and assumptions] [e.g., choosing specific styles of clothes during family reunions on culturally specific holidays].

The use of language

Listen to what is being said, how it is being stated, and the tone of dialogues among participants, not simply observe.

Cycles of behavior

This relates to keeping track of when and who performs whatever behaviors or tasks and how frequently they occur. Keep track of when this activity occurs in the context of the environment.

The sequence in which events occur

Take note of the order in which behaviors occur or the precise moment when actions or events occur, as well as their importance. Also, stay alert for occasions when these sequential patterns of behavior or acts deviate.

Subjects’ physical traits

Make a note of any personal features of the people you see if they’re relevant. Note that you should only focus on features that can be plainly viewed [e.g., clothes, physical appearance such as tall or short] unless this data can be validated in interviews or through documentary proof.

Expressive body motions

Body posture and facial expressions are examples of this. It’s also worth considering if expressive body motions complement or contradict the conversational language [e.g., identifying cynicism].

Techniques for Sampling

The technique of selecting a subset of the population for the study is referred to as “sampling.” In qualitative research, which includes observation as one method of data collecting, non-probability and planned sampling is utilized instead of the probability or random techniques utilized in quantitative studies. Sampling is flexible in participant observation, and it typically continues until no new themes emerge from the data; this is known as data saturation.

Every sample choice is done with the explicit intention of obtaining the most comprehensive source of data possible in order to meet the study goals.

Before you begin the study, you should decide what you’d like to examine, what actions must be documented, and what study question you want to answer. These questions will decide the sampling methodology you should use, so ensure you’ve answered them all before choosing one.

When doing an observation, there are several ways to sample:

- Ad Libitum is a Latin phrase that means “on the spot Sampling is similar to what individuals do in the zoo, for example, when they observe whatever appears to be fascinating at the time. There is no systematic way to keep track of your observations; you jot down whatever comes to mind at the moment. This strategy has the benefit of allowing you to see somewhat infrequent or odd actions that might otherwise be overlooked by more carefully planned sample approaches. This strategy may also be utilized to collect preliminary observations for use in developing your final field research. The likelihood of inherent bias toward visible behaviors or persons, resulting in the missed of boring or recurring patterns of behavior, and the likelihood of missing brief encounters in social contexts are all issues with this technique.

- Behavior Sampling is monitoring the complete group of subjects and noting each occurrence of certain behavior of interest, as well as the names of the people involved. The approach is frequently used in conjunction with focus or scan approaches [see below] to record unusual behaviors overlooked by other sampling methods. However, sampling might be skewed towards certain behaviors that stand out.

- Continuous Recording keeps a detailed record of behavior, including frequency, duration, and latencies [the time between a stimulus and a reaction]. This is a difficult strategy to utilize because you’re trying to record everything that happens in the environment, and so evaluating dependability may suffer as a result. Furthermore, durations and latencies may only be trusted if subjects are present during the data gathering process. On the other hand, this approach allows for the analysis of behavior sequences and assures the collection of a wealth of information about the observation location and the individuals that inhabit there—this sort of sampling benefits from the usage of audio or video recording.

- Focal Sampling is studying a single person for a set period of time and capturing all occurrences of that person’s behavior. Typically, you keep track of the length of a set of specified categories or sorts of behaviors you are interested in watching [e.g., when a teacher travels around the classroom]. This method is less likely to favor one faction over another and gives a lot of information on a person’s conduct. However, you’ll probably need to run many focused samples with this approach before you have a solid picture of how group members interact. Sometimes it can be difficult to maintain one person in sight for the duration of observation without becoming invasive in some situations.

- Instantaneous Sampling is a method of dividing observation periods into small intervals separated by sample points. The observer notes whether or not specified behaviors of interest occur at each sample point. This approach is ineffective for collecting short-duration discrete events, and observers will commonly desire to capture unusual behaviors that occur just before or after the sample point, resulting in a sampling mistake. This approach, though not accurate, gives you a notion of durations and is pretty simple to use. It’s also useful for capturing behavioral traits such as movement or body postures that occur simultaneously.

- One-Zero Sampling is akin to an instant sample in that the investigator records whether the characteristics of concern occurred at any time during the time rather than only at the selection moment. The strategy is excellent for obtaining data on patterns of behavior that just start and end often and abruptly but only endure a short time. Because you get a dimensionless score for the whole recording session using this technique, you only get one set of data for each recording session.

- Scan sampling entails conducting a survey of the whole observed unit and documenting what each member does at the moment. This is crucial for acquiring group statistical information because it guarantees that data is dispersed fairly among persons and time periods. On the other hand, this method may favor more visible activities, and you could miss a lot of what’s going on in between observations, especially unusual or distinctive acts. It’s also difficult to photograph a group of more than a few individuals without losing track of what each individual is doing at any given time [for example, youngsters seated at a table during lunch]. This sort of sampling benefits from the usage of audio or video recording.

Writing Style and Structure

The research issue, the theoretical framework that guides your analysis, the observations you make, and/or special rules specified by your professor all influence how you construct your field report. Because field reports don’t have a set format, it’s a good idea to talk to your professor about the best structure and organization before you start writing. It’s important to keep in mind that field reports should be written in the past tense. With this in mind, most social science field reports include the following elements:

A brief introduction

The research challenge, particular research objectives, and essential ideas or concepts supporting your field study should be described in the introduction. The introduction should define the structure of the organization or context in which you perform the observation, the kind of observations you have made, the focus of your observations, when you observed, and the data collection techniques you utilized. This descriptive material should be taken together to support why you choose the observation place and the persons or activities that occur there.

You should also review relevant literature relevant to the research subject, especially if previous studies employed comparable approaches. Finish your introduction with a remark regarding the structure of the body of the article.

Activities Description

Because they were no witnesses to the circumstance, persons, or events you are writing about, your readers’ sole information and comprehension of what happened will come from the descriptive part of your report. Given this, you must offer enough information to contextualize the analysis that follows properly; don’t make the mistake of offering a description without context. A field report’s description part is akin to a well-written piece of journalism. As a result, answering the “Five W’s of Investigative Reporting” is a valuable method for carefully explaining the many components of an observed scenario. These are, as Dubbels points out [p. 19]:

- What you saw — explain what you saw. Take note of the chronological, physical, and social constraints you set to restrict your observations. What were your initial thoughts about the situation you were witnessing? For example, as a student teacher, how do you feel about using iPads as a learning tool in a history lesson; as a cultural anthropologist, how do you feel about women participating in Native American ceremonial rituals?

- Where — offer context for your observation by providing background information about the location and, if required, noting relevant material things that assist contextualize the observation [e.g., computer layout concerning student involvement with the teacher].

- When — keep track of the day’s events, including each observation’s start and finish times. It’s also worth noting that you might need to provide background information or crucial events that influence the scenario you’re witnessing [for example, evaluating instructors’ ability to re-engage kids after returning from an unscheduled fire drill].

- Who — make a note of the persons being observed’s the background and demographic information, such as age, gender, race, and/or any other data relevant to your research]. Keep track of who is doing and saying what and who is not doing or saying anything. If applicable, make a note of who was absent from the observation.

- Why – Why were you doing this in the first place? Describe why you chose to observe certain occurrences in particular. Take note of why anything occurred. Keep in mind why you could have included or removed particular details.

Analysis and Interpretation

Always position your field observations’ analyses and interpretations in the context of the theoretical assumptions and concerns you discussed in the introduction. While studying the data, part of your job is to figure out which observations are worth commenting on and interpreting and which ones are more generic. These judgments are made possible by your theoretical framework. You must show the reader that you are performing field research through the eyes of a knowledgeable observer and a casual observer.

Recommendations and Conclusion

The conclusion should include a concise summary of the whole study, as well as a reiteration of the value or relevance of your findings. Any new knowledge should be avoided. You should also provide any recommendations you might have based on your findings. Make a note of any unexpected issues you experienced, as well as the study’s limits. There should be no more than two or three paragraphs in the end.

This is where you would include non-essential material that supports your analysis [particularly repetitious or long material], confirms your conclusions, or contextualizes a related issue that helps the reader grasp the full report. Figures/tables/charts/graphs showing findings, statistics, photos, maps, sketches, or, if relevant, transcripts of interviews are all examples of information that might be included in an appendix.

There are no restrictions on what can be included in the appendix or how information is presented [e.g., a DVD recording of the observation location]. It is related to the study’s goal and is mentioned in the report. If there are many appendices [“appendices”), the order in which they are grouped is determined by the order in which they were first mentioned in the report’s text.

Bibliography

List all of the sources you used to research and gather information for your field report. It’s worth noting that most field reports don’t contain further readings or a lengthy bibliography. However, speak with your professor about what sources should be included in your list, and make sure to write them in the citation style that your discipline or your professor prefers [i.e., APA, Chicago, MLA, etc.].