For as long as the medium of film has been around, it has been used to push stereotypes about vulnerable and underprivileged groups for the purposes of fostering racial hatred and solidifying societal control. Anyone who’s ever watched a “classic” film or a TV series like I Love Lucy can see, for example, how women were depicted as simpletons and dolts who needed to be controlled by their domineering, abusive husbands in order to be happy. Similarly, film and TV have helped perpetuate harmful stereotypes about African-American, Latino and Asian people from The Birth of a Nation to the present day. These stereotypical images of minorities are not only offensive, they have helped entrench white supremacy and structural racism in our society by reinforcing negative attitudes towards these minorities.

While it may seem like racism and prejudice have been wiped away in modern Hollywood, the reality is that racial stereotypes and norms are now being enforced in a different way. The “coon caricatures” of the 1930’s and 1940’s have given way to a new cliché: the “magical negro,” an impossibly perfect figure whose role is to provide guidance and support for privileged white people. The magical negro figure, while seemingly benign, is its own form of violence against African-Americans, because it creates an unrealistic ideal for them to live up to and also continues to subordinate their wants and desires to those of white people. By analyzing the history of racial stereotypes in film, we can better understand why the magical negro stereotype exists and why it needs to be extirpated if our society hopes to rid itself of the stain of white supremacy.

The magical negro term was coined by film director Spike Lee in 2001 as a criticism of why Hollywood directors continued to use the archetype in their films (Seitz 2010). A magical negro is defined as a character with no backstory and no relevance to a film’s plot aside from their role in aiding the white protagonist. Films such as The Green Mile, The Shawshank Redemption and Th Matrix have hinged upon magical negro characters who lack fully-defined personalities and character arcs, who essentially serve as living props upon which the white protagonist can rely at critical moments. Lucius Fox, Morgan Freeman’s character in Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, is one of the most notable examples of a magical negro in recent film. Fox has no personality beyond serving as a mentor figure to Bruce Wayne, offering him advice and assistance whenever he is in a jam, and lacks any personality characteristics beyond these qualities. Freeman in particular is known for taking on magical negro roles in many films, such as the aforementioned Shawshank Redemption.

The reason why the magical negro character is so damaging to African-Americans is because it denies them any agency. Magical negroes have no unique qualities beyond wisdom and no role other than to help the white protagonist. In effect, they exist merely as window dressing in a white person’s story, with no flavor and distinctiveness of their own. This is a rather depressing reflection of America’s white supremacist culture in general, where African-Americans are expected to take a backseat to white concerns and white interests, and are never allowed to have a voice of their own. Both right-wingers and liberals seek to deny African-Americans a voice whenever they decry racism, on the basis that we are supposedly a color-blind and free society now.

This ignores the incredible poverty that African-American communities continue to suffer from as well as the violence being visited on black bodies every day through corrupt, racist police forces and the military. Even in films in a supposedly post-Jim Crow era, African-Americans are not allowed to control their own destinies, but are expected to sit patiently and wait for white masters to give them a bone. Whatever positive role a magical negro may play in the story of a film is negated by the fact that they exist solely to benefit a white person. In effect, the magical negro is a slave, like African-Americans were enslaved by whites throughout the first part of America’s society. The magical negro’s slavery is not literal, but his or her existence is enmeshed with and enslaved to that of a white protagonist, and it is only that protagonist’s story that matters. The magical negro is never given a moment to shine on his or her own, freed from the shackles of the story they are cast in. They are allowed to speak when whites allow them to speak, must fade into the background when whites get bored of them, and are punished or killed if they step out of line. This is an inadvertent parallel to how African-Americans are treated in the real world and an example of why the stereotype is so harmful.

The other major problem with the magical negro stereotype is that it denies African-Americans the ability to be flawed (Andrews 2013). Human beings naturally have flaws and defects because no one is perfect and people invariably have their quirks. Indeed, it is the exploitation and abuse of character flaws that often makes for interesting fiction; for example, Shakespeare’s play Othello is driven by the paranoia of its titular protagonist. However, magical negro characters have no flaws whatsoever; they are depicted as shining beacons of light that white protagonists can look to when their lives get too dark. Part of this is because magical negroes are not allowed to have characters and personalities by definition, because giving them actual personas would intrude upon the oh-so-wonderful story of the white protagonist. However, even when magical negroes are given a decent amount of screen time, they are depicted as having no flaws in their characters.

The aforementioned example of Lucius Fox in the Batman movies is a perfect example: he has no real character flaws, makes no mistakes, and actually serves as Bruce Wayne’s conscience over the course of the movies. This conceit is almost certainly a product of white guilt; in a bizarre attempt to atone for all the violence and harm they’ve inflicted on black bodies throughout the centuries, white people think that depicting blacks as being flawless in fiction will make up for the very real crimes against humanity they’ve committed. Beyond the incredible arrogance of this notion, the magical negro’s lack of flaws directly hurts African-Americans by giving them a standard that is impossible to live up to. As mentioned above, human beings inherently have flaws; there is simply no way around this fact. It’s also self-evident that people in general look to films and TV shows for role models for their behavior.

What we see on the big and small screens influences our behavior and sets the tone for society to follow, which is why it was a big deal when, say, Will and Grace openly depicted gay couples on mainstream, network TV. The magical negro harms African-Americans by providing them with black characters that they cannot relate to and cannot ever hope to emulate. Because they are expected to live up to a standard that no human being of any race could ever possibly meet, this internalizes failure and depression in the black mind, reminding them that they can’t measure up and succeed in society. In effect, the magical negro helps reinforce white supremacy by telling African-Americans that they will never be good enough to make it in a white man’s world. Jim Crow and legalized racism used to accomplish this goal through government-enforced segregation and extralegal justice in the form of the Ku Klux Klan, sunset towns and random lynchings; now Hollywood helps enforce it by creating unrealistically positive African-American characters that no actual African-American can ever hope to imitate.

In a very mild defense of the whites who perpetuate the magical negro myth, their continued insistence on using the archetype likely stems from a desire to distance Hollywood from its more openly racist past. During the first few decades of its existence, mainstream American films promoted openly bigoted stereotypes of African-Americans, depicting them as slow-witted, cowardly, and overly servile to whites. Even when film depictions of African-Americans weren’t overtly hostile, they only showed African-Americans in servant roles to white people, never having central roles of their own. For example, Stepin Fetchit was a notable African-American actor who became famous for portrayed characters who were dumb, lazy, and mindlessly obedient to white masters. Additionally, many films simply didn’t feature black characters at all, with many “classic” films of the 1930’s through the 1950’s deliberately having all-white casts. In this context, at least on the surface, the magical negro is a step-up in regards to stereotyping, because it at least tries to be positive instead of being wholly negative.

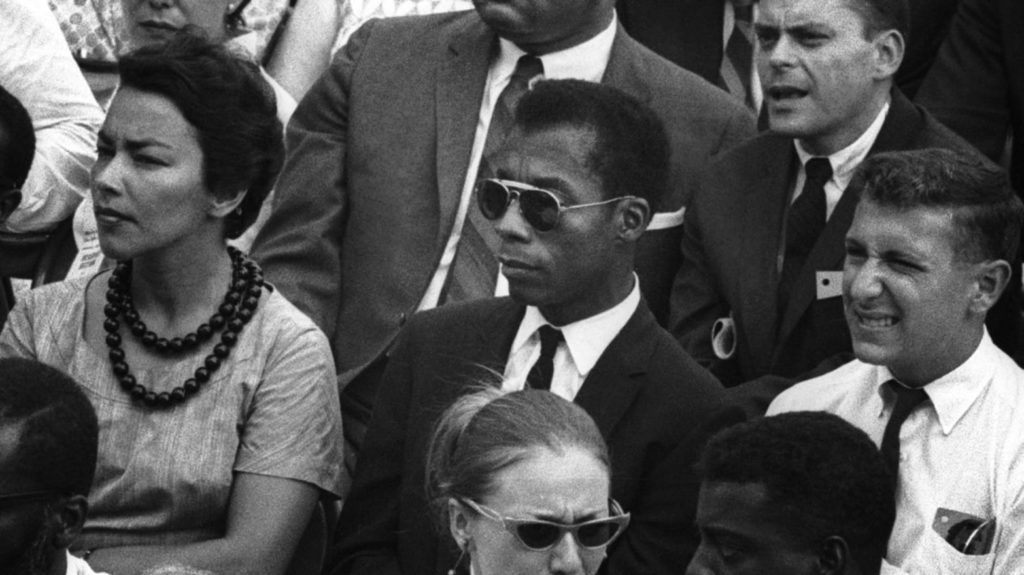

The 1960’s saw the initial birth and popularity of the magical negro stereotype. Responding to the Civil Rights’ Movement and changing cultural mores, Hollywood began making films and TV series that depicted blacks in a more positive light. Unfortunately, they didn’t even attempt to depict the nuances and complexities of African-American life, resulting in one-dimensional characters that represented a switch of extremes: from wholly negative and mean-spirited to wholly positive and patronizing.

One of the most prominent examples of a magical negro character from this era is Sidney Poitier’s role in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. This film is typically considered a groundbreaking achievement in American cinema, as it positively depicted a black man having a romantic relationship with a white woman. However, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner inadvertently helps reinforce white supremacy through its characterization and plotting. John Prentice, Poitier’s character, is depicted as impossibly flawless and respectable—indeed, director Stanley Kramer specifically designed the character to be unrealistically wise and accomplished—and is someone who could not exist in real life.

Moreover, Prentice essentially exists as a blank slate and a means by which there can be conflict between the other (white) main characters. Prentice is never given agency and he is not allowed to be a complete human being; he merely exists as a prop that Spencer Tracy’s, Katharine Hepburn’s and Katharine Houghton’s characters can punt around in their interactions. He could be replaced by any other black man and it wouldn’t have made a difference. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner is merely a mirror reflection of the “coon caricature” films that Stepin Fetchit starred in three decades prior, in that it paints a world in which only white people have agency, only what white people want and need matters, and African-Americans are expected to act as handmaidens and footstools on the path to white glory. The real absurdity is that this deeply reactionary and racist film was considered “progressive” in any way, shape, or form.

Another example of early tokenism in the form of the magical negro stereotype was Nichelle Nichols’ character of Lieutenant Uhura on the original Star Trek series. Star Trek itself is an example of white supremacy masquerading as white progressivism and anti-racism, in that Gene Roddenberry specifically created a multiracial, multinational crew for the starship Enterprise, on the basis that racial prejudice would cease to exist in the far future and people from different ethnic backgrounds would work in harmony (Golumbia 1995). However, Roddenberry didn’t bother to depict this transition in any meaningful way by giving his ethnic minority characters—Uhura and Lieutenant Sulu—unique personalities or characters. The only distinguishing feature that Uhura had was that she was black, while Sulu was only distinguished by being Asian; virtually all screen time was given to the white protagonists Captain Kirk, Spock and Leonard McCoy.

To illustrate how little thought the creators of Star Trek gave to Uhura, her character didn’t even have a first name until the J.J. Abrams-directed reboot movie in 2009, nearly two decades after Roddenberry’s death. Sulu fared a little better; he finally got a first name in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, the final film starring the entirety of the original series’ cast. Both in the original TV show and in the movies that were filmed in the 1970’s, 1980’s and 1990’s, Uhura was given no unique character traits and effectively functioned as a secretary, despite the idea that her role was groundbreaking by the standards of television at the time. Nichols’ character was given no significant depth or flaws and merely existed as a source of advice for Captain Kirk and the other senior Enterprise officers.

Because she was female, in addition to typical magical negro characteristics, Uhura was also made into a sexual foil for William Shatner’s character, which was formalized when they kissed during the episode “Plato’s Stepchildren,” one of the earliest instances of an interracial romance being depicted on a TV show. Given the history of white men forcing themselves on black women sexually during both the era of slavery and after, this adds an uncomfortable element of sexual predation to the already heavy magical negro aspects of Uhura’s characters. It is not enough for whites to cast African-Americans in roles as menial advice-givers with no unique personality of their own; they must also colonize black bodies and use them for their sexual games.

Amusingly, Star Trek’s producers never learned their lesson from the case of Uhura, and in fact repeated it when Star Trek: The Next Generation debuted in the 1980’s. This show featured Whoopi Goldberg in the role of Guinan, a magical negro character whose sole purpose was to give friendly advice to Captain Jean-Luc Picard. While later episodes of Next Generation gave Goldberg’s character marginally more depth, it was ultimately impossible for the series’ creators to escape the magical negro they had created.

It’s clear from the continued use of the magical negro stereotype in film and TV that Hollywood is still in the throes of white supremacy. Instead of enforcing racism through the depiction of African-Americans as cowardly simpletons, they reinforce it by depicting them as saints to be idolized, saints whose sole purpose is to aid white people on the road to paradise. The magical negro stereotype does not represent Hollywood cleansing itself of its history of white supremacy, but merely cloaking it in different clothing, and the harm that their stereotypes continue to inflict on black minds and black bodies is palpable. It is incumbent on us to point out these harmful stereotypes wherever they rear their ugly heads, explain why they are so harmful to African-Americans, and combat them as viciously and as uncompromisingly as we can. This is the only way we can break the chains of white racism and ensure a more just world.

Works Cited

Andrews, Helena. “‘The Butler’ Versus ‘The Help’: Gender Matters.” The Root. 23 Aug. 2013. Web. 07 May 2017.

Bernardi, Daniel. “”Star Trek” in the 1960s: Liberal-Humanism and the Production of Race.” Science Fiction Studies (1997): 209-225.

Glenn, Cerise L., and Landra J. Cunningham. “The power of black magic: The magical negro and white salvation in film.” Journal of Black Studies 40.2 (2009): 135-152.

Golumbia, David. “Black and White World: Race, Ideology, and Utopia in” Triton” and” Star Trek”.” Cultural Critique 32 (1995): 75-95.

Harris, Glen Anthony, and Robert Brent Toplin. “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?: A Clash of Interpretations Regarding Stanley Kramer’s Film on the Subject of Interracial Marriage.” The Journal of Popular Culture 40.4 (2007): 700-713.

Hughey, Matthew W. “Cinethetic racism: White redemption and black stereotypes in” magical Negro” films.” Social Problems 56.3 (2009): 543-577.

Scott, Anna Beatrice. “Superpower vs supernatural: black superheroes and the quest for a mutant reality.” Journal of Visual Culture 5.3 (2006): 295-314.

Seitz, Matt Zoller. “The offensive movie cliche that won’t die.” Salon. 14 Sept. 2010. Web. 07 May 2017.