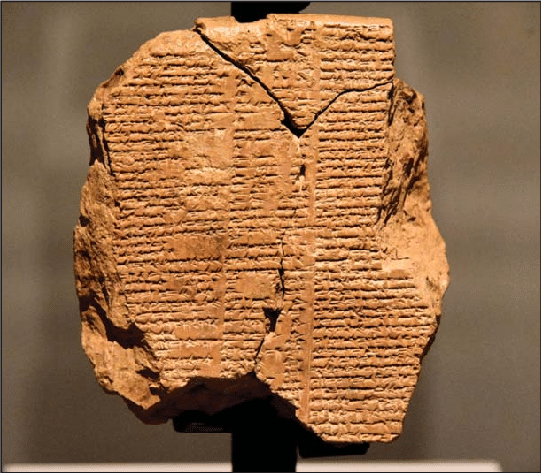

Dreams in Epic of Gilgamesh and Genesis

In much of human history, dreams are seen as portent, signs, and omens relaying reliable information about current or future happenings. When analyzing the religious texts of the Torah and the Epic of Gilgamesh, literary experts have concluded that the two sacred texts have interconnected themes, such as mortality, sin, and divine intervention (Ceil, 2016). The essay will compare dreams in the Epic of Gilgamesh to dreams in the Book of Genesis.

In Genesis 41, Joseph interprets two dreams for the Egyptian King, Pharaoh, while imprisoned. Since the King dreamt and as an outcome of the dream interpretation by Joseph, the King prepared his land for the coming seven years of famine following seven years of plenty. The king believed the dreams to be an accurate indication of what was going to happen. In Gilgamesh, a similar attitude is shown when Gilgamesh has three dreams, and his wise mother interprets the dream for Gilgamesh. Anytime Gilgamesh has a dream, he immediately infers his mother for interpretation, as he believed that the dreams were an accurate portent of what was happening or going to occur.

Despite having significantly varying plots, the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Genesis relay similar symbolic meanings in how they utilize dreams. The Epic of Gilgamesh, for instance, is linked with Noah’s ark, while Gilgamesh looks like Adam in the book of Genesis, beaten by a snake. In the book of Genesis, Jacob has a dream in which he wrestles with Gods Angel, asking for a blessing. The same is in the Epic of Gilgamesh; Gilgamesh, the tale’s protagonist, wrestles with a divine creature to affirm his hero’s identity and right to triumph over others.

Dreams in both the Bible and the Epic of Gilgamesh suggest that the only way a man can live virtuously is by adhering to God’s demands and making moral decisions. Another fundamental similarity between the two literary texts is their literary context. In both the Epic of Gilgamesh and the book of genesis, dreams are employed to predict future occurrences, establish a link between the supernatural and human beings, and help them accept the supernatural as the ultimate destiny.

One significant difference between the book of Genesis and the Epic of Gilgamesh lies in the identity of the dream interpreter, as relayed by the Quick, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, the symbolism of dreams in most cases interpreted by women. Females with the innate ability to explain the symbolic meaning of dreams belonged to a particular social class, šā’ilta. The women in the šā’ilta social class were chosen by an assembly of gods to relay their messages and wishes to the ordinary folks (Holloway, 2018). In the book of Genesis, dreams, in most cases, are used among the male prophets. For example, when Jacob dreams of a staircase stretching to heaven, he appreciates the connection between human beings and God (The Holy Bible, NIV, and Genesis. 28. 12-15). By sending Jacob the dream, God also gives him the ability to comprehend its meaning: in the days to come, Jacob will have many descendants and later blessed in the Lord’s chosen nation. Another example from the Book of Genesis refers to Jacob’s son Joseph, who has the God-given ability to explain dreams (Holloway, 2018). Joseph had a vision of binding sheaves of grain leaning towards him. Joseph is proclaiming his authority over his older brothers (Genesis. 37. 7). Only Joseph understands that he will be the leader among his family and over God’s chosen nation. Like his father, Jacob Joseph does not call on other people to interpret his vision but patiently waits on God to reveal its meaning to him.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the initial encounter of dreams is relayed at the end of the first tablet when Gilgamesh dreams of a significantly giant meteorite, that he cannot lift or turn. The meteorite falls on earth. Gilgamesh states that people marvel at the meteorite while he values it as much as a wife or a friend. Ironically, his mother calls on him to challenge the great meteorite. Oddly, Gilgamesh gets a second dream similar to the first dream. In the second dream, the meteorite is replaced by an ax, and the ax appears on Gilgamesh’s doorstep. Gilgamesh requests his mother, a goddess, for the interpretation. She states that the two dreams show that a great person with mighty will come to the city shortly, and just like a wife, the protagonist will embrace him, and the individual will be a basis of success to Gilgamesh and the city. Just as foretold, Enkidu, a mighty man, arrives in Uruk, and after a battle, they become best friends and confidants. Gilgamesh and Uruk go on to attain immense success.

In the bible, Abraham has a vision. Abraham’s vision is equally complicated as Gilgamesh’s dream. Abraham is shown an infinite number of stars, and God reveals that the stars indicate the significant number of descendants he will have. The similarity between the two visions is that they both foretell greatness. Gilgamesh’s vision foretells of coming of a mighty man that will become his close friend (Lambert & Tigay, 2015). Abraham’s dream foretells of having a significant number of descendants through his son Isaac. Coincidentally the occurrence of the two events will result in greatness. In his escapades with Enkidu, Gilgamesh achieved a lot, and through his son Isaac, Abraham had many descendants and built a great nation. Like Enkidu and Gilgamesh first had a duel before becoming friends, God tests Abraham by calling on him to sacrifice his son.

How dreams are revealed to Gilgamesh in the Epic is remarkably similar to Genesis’s visions. In the fourth tablet of the Epic, the dreams of Gilgamesh are induced spiritually. On their way to the cedar forest, Gilgamesh prays to Shamash, who in turn sends Gilgamesh terrifying dreams (Lambert & Tigay, 2015). Gilgamesh finds solace in his friend, who sees the scary dreams as a sign of good things to come. In the book of Genesis, Abraham and other characters pray and fast to seek visions and direction from the Almighty. Gilgamesh’s friend Enkidu has visions, but Enkidu’s dreams are not spiritual as they are brought about by fever.

Noah and Utnapishtim’s dreams and visions are remarkably similar. Utnapishtim relays details of his dream while narrating to Gilgamesh the troubles he had to endure to attain immortality. The flood is Utnapishtim due to the counsel of God’s anger just as it is with Noah’s surge in the Book of Genesis. The council of God’s decision to destroy the world is revealed to Utnapishtim in a dream. Just as revealed in Noah’s vision, the floods were all caused by man’s evil ways. In both the narratives, both the protagonists are virtuous individuals.

The similarities in the visions are remarkable. Just like Noah, Utnapishtim in the vision was also called upon to build a boat. While Noah’s boat had fewer compartments, both the boats were compartmentalized to house many creatures the protagonists intended to bring aboard. While the shape of the boats differs, Utnapishtim was square while the boat in Genesis is rectangular higher powers, in all cases ordered the boats to have at least a single window.

Conclusion

The use of dreams is one of the most distinctive traits of ancient literature, with clear examples in the Hebrew Bible and the Epic tale of Gilgamesh. Despite the differences in the religious texts, purpose, and outlay, the visions and dreams of the protagonists carry the same principal messages dealing with the themes of mortality, sin, and the role of divine power. However, for Mesopotamians, women usually give the meaning of dreams, while n the Hebrew bible, the power of interpreting dreams and visions is solely by God, who only gives it to those meant to get the message.