Abstract

Public policy should aim at maximizing public benefit and this cannot be achieved with aids to the survival of any airline or the aviation sector but with the preservation of connectivity. Public policy should preserve connectivity. The decision to nationalize Alitalia spurs disbelief in the company’s ability to become lucrative, discontentment at the use of public funds to support it, and objections to the possible competition distortion it may cause. This article analyses the effect of the state aid to Alitalia from the standpoint of international long-haul connectivity. It also discusses the difficulties of assessing distortions in competition derived from this measure alone in the highly subsidized European aviation sector.

Keywords: public policy, airline, competition, connectivity, state aid

Connectivity and Public Policy – State Aid to Alitalia

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a severe economic crisis in the entire world. To prevent contagion, States imposed border closures, lockdown, and social distance measures that impaired proper economy functioning and led to a global recession. These measures caused aviation capacity to drop sharply and rapidly. With few exceptions, airlines had no liquidity to face the capacity restrictions and had indebtedness levels too high to have access to non-state funds.

Italy (2020) decided to nationalize Alitalia and this decision caused fear of perpetuating the company’s long-history of continuous losses and state support, and that the measure would distort competition of other carriers. There is also a generalized perception that Alitalia’s demise would not jeopardize air service that would continue to be served by other carriers. This article discusses the proposed nationalization of Alitalia from the standpoint of air connectivity.

Theoretical Framework: State Aid to Airlines

No previous aviation crisis is comparable to the COVID-19 pandemic in speed, breadth, and intensity. Nonetheless, the exam of the Air Transportation Safety and System Stabilization Act (ATSSSA) sheds light on the rationale of granting state aid to airlines during crises. Following the terrorist attacks of September 9, 2001, the USA transferred USD$18 billion to airlines under the ATSSSA.

Lewinsohn (2005) argues that ATSSSA did not aim to guarantee the survival of any airline or to rehabilitate the commercial aviation industry, but rather to serve as a public relations measure to reestablish the airlines’ position before the attack because the instrument of attack was an aircraft. He reasons that the symbolism of airlines’ mass bankruptcy was the moral justification for the aid and that bankruptcy proceedings would force the courts to analyze each companies’ particular predicament and make more concessions a normalized market would demand.

de Rugy and Leff (2020) believe the aviation sector should not receive any specific aid to face the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. They argue that the decision of a state to aid a sector or company should be objectively linked to (i) the systemic risk of the sector or company’s collapse affect the economy as a whole, or (ii) the possible spillover effect to other sectors or companies causing relevant damage to the economy as a whole. Furthermore, they argue that the collapse of many airlines does not cause systemic risk to the economy and that any spillover effect to sectors that depend on them may be dealt with by the bankruptcy proceedings in the USA.

It should be noted that their analysis is limited to the USA market and furthermore systemic risk and spillover effects differ according to how an economy is organized and the quantity and importance of economic activities that depend on aviation.

COVID-19 Effect on Connectivity

Aviation, and particularly international aviation, has a relevant contribution to Italy’s economy. A country’s economy is measurably impacted by aviation connectivity. Perovic (2013) reports that “a 10 percent increase in global connectivity (relative to GDP) would see a 0.07 percent increase in long-run GDP per annum”.

(Table 2)

“Air connectivity can be broadly defined as ability and ease with which passengers and freight can reach destinations by air” (OECD/ITF, 2018). Methodologies of calculation of connectivity indexes differ substantially. Regardless of the index used, however, Italy has low connectivity.

(Table 3)

COVID-19 changed the profile of international air connectivity, both in nature and in frequency. Suffice to say that London-New York dropped from number 8 to 18 in the rank of city pairs by passenger jet seats flown in the 38th week of 2019 (Cirium, 2020).

(Table 4)

Many countries adopted tax and expenditure measures addressed both at the economy as a whole and specific economic sectors or companies more intensely affected by the pandemic. Broadly, the rationale for such measures was to allow continuity of economy activity until movement restrictions were lifted. Such measures were devised to be temporary, and in most cases, they expire before the end of 2020.

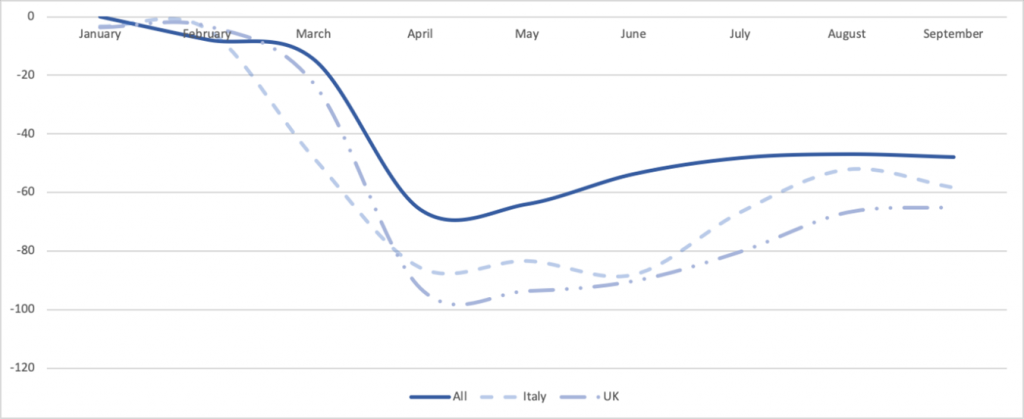

In April 2020, there was an implicit expectation that by September 2020, the pandemic would be reasonably controlled so that restrictions on people’s movement could be lifted. Demand would return, albeit to lower levels than those pre-pandemics. As we write this article in September 2020, neither restrictions on people’s movement have been lifted, nor demand shows signs of recovery (Figure 1). There are many possible explanations to this situation.

The feasibility of aviation depends on consistently free international movement. Countries across the globe have adopted unilateral and uncoordinated approaches to border closures and restrictions.

Passengers’ confidence in the sanitary safety of air transport has not yet been restored. Recent studies suggest that seat proximity is strongly associated with infection risk and that transmission occurs even between passengers in the business class where seats are widely spaced (Khanh et al., 2020).

Passengers also lack confidence in the reliability of schedules frequently changed by short-notice cancellations. Passengers risk being left with a voucher if flights are canceled due to last-minute changes on border restrictions.

The LCC business model is suffering because of the various measures imposed by the states or adopted by competitors to guarantee sanitary safety in air transportation. Such rules result in higher turnarounds to sanitize the aircraft, constraints on aircraft capacity utilization to comply with social distance guidelines, and higher ticket sale costs from passenger health tracking.

The sharp decline in business travel harms profitability of the international long-haul flight segment. In 2019, revenue from premium cabins (business and first class) represented 31.2% of all international revenue (IATA, 2020). Most businesses were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and are cutting costs. Videoconferencing has largely replaced business meetings. Even if business travel recovers, a big portion of it will be permanently lost. In an effort to lure demand, carriers are waiving change fees and reducing ticket prices, blurring the difference between business and coach advantages. Border restrictions and closures impact may extend the stay of key executives in foreign countries. FSCs whose revenue is predominantly from international flights, such as European and Middle Eastern airlines, will be more affected.

Even if border restrictions were lifted and passenger confidence was restored, the recovery of demand to levels comparable to those pre-pandemic would probably depend on lower airfares. The global economy has plunged into an unprecedented recession. As of June 9, 2020, the projected worldwide industry net post-tax loss was US$84.3 billion, more than three times the US$25.9 billion net post-tax profits in 2019 (IATA Economics, 2020).

Lower airfares are typically offered by LCCs with superb cost management and revenue maximization practices. However, requirements of social distancing inside aircraft imposed by some countries, such as Italy (Dragoni, 2020), are likely incompatible with this model.

The scenario is dire not only because of the sharp decline in capacity but because there are not minimum conditions for aviation to operate as a business aimed at making a profit (i.e. international conventions on sanitary measures on air transportation, coordinated border restrictions).

Public policy should aim at maximizing public benefit. This is not achieved with the survival of any airline or the aviation sector but with the preservation of connectivity. Public policy should preserve connectivity.

The COVID-19 pandemic critically jeopardizes air connectivity reducing its breadth and frequency. Public policies need to address this in line with their countries’ priorities. Even in a scenario where there are minimum business feasibility conditions, connectivity cannot be achieved without public policy. Airlines will plan routes and set fares according to their profitability or expansion goals, which may or may not coincide with the state’s needs (House of Commons Transport Committee, 2013). Furthermore, state aid focused on connectivity would result in more public benefit and less distortion in competition.

EU Rules on State Aid

Italy (2020) has decided to nationalize Alitalia with initial funding of €3 billion. The implementation of the decision should have occurred in June, but to this date, the European Commission has not approved it.

Regulating and restricting state aid is essential to the EU because (i) political cycles are shorter than financial cycles and politicians may be tempted to guarantee a successful political cycle with state aids; and (ii) Member-States do not operate under a strict budgetary restriction, and fiscal indiscipline is transferred to other jurisdictions through currency devaluation (Heimler & Jenny, 2012).

Article 107 of the TFEU states that any aid granted by a Member State or through State resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favoring certain undertakings shall, in so far as it affects trade between Member States, be incompatible with the internal market. However, item 2 (b) states that aid to make good the damage caused by natural disasters or exceptional occurrences shall be compatible with the internal market.

The Temporary Framework sets out the criteria under EU State aid rules based on which Member States may provide public support in the form of equity or hybrid capital instruments to undertakings facing financial difficulties due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The purpose of the recapitalization is to restore the capital structure of the beneficiary predating the outbreak. The beneficiary of public support shall not be an undertaking that was already in difficulty on December 31, 2019, within the meaning of the GBER.

Alitalia was under extraordinary administration on December 31, 2019 and thus would be ineligible to the support. The interpretation of “undertaking in difficulty” should reckon with the rationale of the rule and take into consideration that Alitalia was literally about to end its voluntary administration. There was a market solution frustrated precisely by the COVID-19 crisis.

On March 6, 2019, Amministrazione Straordinaria di Alitalia (2020) called for expression of interest in the acquisition of the companies’ assets and received offers. The call was suspended due to the COVID-19 crisis (Camera dei Deputati, 2020).

Furthermore, “the Commission has approved national aid to rescue companies on the verge of collapse and whose viability was questionable long before December 2019” such as the loan to Transportes Aéreos Portugueses (TAP) (Ferri, 2020)

The European Commission is demanding there is economic discontinuity between Alitalia and the entity that will absorb part of its assets and activities as a condition to the approval of the nationalization (ANSA, 2020). The rationale is that not only Alitalia is a business in distress, but that it has been in distress for decades. It has received millions in state aid it has not repaid. Nor has it improved its operational performance. Keeping an unfeasible business artificially afloat with state resources will negatively impact Italy’s economy and, consequently, the EU economy. New aids should be conditioned to repayment of previous ones or to such a clean break between the entities that it stands clear that the new entity is not benefiting from previous subsidies.

While the nationalization’s approval is not obtained, Alitalia will rely on a €199.45 million grant approved by the European Commission on September 4, 2020 for damages from March 1 2020 to June 15 2020 resulting from the travel restrictions (European Commission 2020).

Despite any objections to this measure, the state aid to Alitalia preserves Italy’s international long-haul connectivity. As Alitalia (2020b) points out, “the Italian aviation market is very contestable and characterized by 3 important elements: 1. a high penetration of LCCs in the domestic market (the highest in Europe) and intra-EU, also due to the recognized incentives of the airport managers; 2. Long-haul operated by other countries’ carriers that feed on their hubs; 3. Presence of many territorial and touristic excellences that favored the development of a network of many medium-sized airports.”

Alitalia and Ryanair share the leadership by carried passengers in domestic flights. Ryanair holds a dominant position by carried passengers on international flights. This number is skewed because ENAC computes as international all European traffic (intra-EU and extra-EU). Ryanair and EasyJet do not serve long-distance international flights to the Americas, Asia, and Africa. In 2018, the fifty biggest LCC routes in Italy by passengers carried were intra-EU (ENAC, 2018).

(Table 5)

(Table 6)

Ryanair’s and other LCCs’ business models are not suitable for serving long-haul international routes. LCCs operate dense, short-distance, and point-to-point routes with high load factors, maximum aircraft utilization, and short turnarounds. Ryanair does offer virtual connections in Rome (FCO), Milano Bergamo (BGY), and Porto (OPO). However, the operation of actual connections in long-haul flights requires a significantly more complex and, consequently, more costly infrastructure. More than one airline unsuccessfully tried to offer the LCC business model in long-distance routes, the most recent example being that of Norwegian Airlines.

The international long-haul market is very segmented. Assuming all international non-European traffic is long-haul, in 2019, (Alitalia 2020a)’s 2,849,025 carried passengers in this segment represented only 13,73% of the total (ENAC 2020). Comparatively, Air China alone carried 17.29% of all Asian Pacific international traffic to Italy in 2019 (ENAC, 2020).

On one side, Ryanair and the LCCs do not serve Italian long-haul international flights. On the other, FSCs may resize capacity offer to the segment according to the reduction in demand and profitability. Interruption or deficiency in the service of long-haul international routes has a direct effect in the country’s economy. And one that cannot be replaced by competitors in the short or medium term.

Concerns About the State Aid to Alitalia

Air connectivity is an important matter of public policy, but many other factors play a part in a decision to nationalize a company. And, in the case of Alitalia, even though connectivity is one factor to be taken into account, other important concerns should be addressed by the government and the future managers of the business.

It is reasonable to expect a low chance of success for Alitalia’s restructuring given its track record of failures. It is understandable to be frustrated by the amount of additional public funds Italy intends to invest in the company, particularly in a period of economic hardship. It has to be noted, however, that the extraordinary administration regime under which Alitalia was since 2017 had many flaws and was never suitable to restructure businesses but to sell companies (Belhocine, Garcia-Macia, & Garrido 2018). Due to the nature and constraints of the Marzano law regime, it is debatable if Alitalia was being managed with the purpose of reorganizing its business to a feasible profitable model or just organizing its assets and accounts to be sold.

It is also natural to be wary of the form chosen to the state aid: nationalization as opposed to the many other financial instruments available to support the company. In the past, the government’s actions suggested national pride plays a part in the decisions concerning the company. In 2008, even though an Air France proposal was deemed better by the experts, Alitalia was sold to Compagnia Aerea Italiana (CAI) supposedly to maintain Italian ownership (La Rocca, Fasano, & Napoli, 2019).

Lastly, having any government as a majority shareholder of an airline business is disquieting. Alitalia, however, is a daunting challenge to any manager. It did not record profits in this decade. It was privatized in 2008 in great part because of the limitations on state aid imposed by the European Commission in 2006. On the brink of another financial distress, had 49% of its shareholding sold to Ethiad, who brought much needed cash but failed to implement restructuring measures. Entered into extraordinary administration in 2017, during which period it received two loans totaling €1,300 million. Its market position continuously declined over the years and its financial situation remains precarious.

It remains to be seen if the government will be able to act as an experienced restructuring professional and make the hard changes needed to restore Alitalia’s feasibility.

The State as a Shareholder and Competition

A nefarious consequence of state aid is that it may distort competition. The state aid incompatible with the EU internal market distorts or threatens to distort competition. Distorts competition the aid that improves the beneficiary’s position compared to other undertakings with which it competes (Akritidou, 2018). This assessment should be made in terms of the effects the state aid produces and not in terms of the objective it pursues (Heimler & Jenny, 2012).

In a usual scenario these effects could be more objectively assessed. But this is not the usual scenario. The European Sky is unified, but the fiscal policy is very much segmented. States have granted aids in various forms (loans, subsidies, direct grants) to their businesses and to their airlines. In Europe, the major FSCs have all received state aid. The grants were given pursuant to the resource availability of each state and not to the importance of the carriers in the European market. Even Ryanair has drawn funds made available by the Bank of England through the COVID Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF).

It is not possible to assess the distortion in competition that the state aid to Alitalia would cause in this scenario of highly subsidized players.

Any assessment of the impact in competition of the state aid to Alitalia should take into consideration the segment it operates in. It should start by defining what market is really being contested. The Italian market is shared by Ryanair and Alitalia, but each operates in distinct segments with distinct offers.

Another concerning consequence of state aid is the de-liberalization of the market. States will be pressured to protect the national carriers in which they invested. It requires much discipline to let the market operate freely when the state is so much invested in one particular player.

General Considerations

Public policy should aim at maximizing public benefit and this cannot be achieved with aids to the survival of any airline or the aviation sector but with the preservation of connectivity. Public policy should preserve connectivity.

The decision to nationalize Alitalia spurs disbelief in the company’s ability to become lucrative, discontentment at the use of public funds to support it, and objections to the possible competition distortion it may cause.

Despite the many reasonable concerns against the measure, the state aid to Alitalia does mitigate the loss of connectivity in the long-haul international segment Italy is facing and may continue to face as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. And the loss of connectivity impacts negatively the Italian economy.

Figures

Note: Week compared with the equivalent week in the previous year, i.e., Monday, January 6, 2020, vs. Monday, January 7, 2019.

Source: Adapted from (OAG 2020)

Figure 1. Global Scheduled Flights Change year-over-year

Tables

Liquidity Equivalent Days of the Leading European Airline Groups

| Group | Liquidity Days | Date of Liquidity

Balance

|

| Wizz Air | 176 | 31/12/2019 |

| Ryanair | 170 | 12/03/2020 |

| Finnair | 133 | 31/12/2019 |

| IAG | 132 | 12/03/2020 |

| Easyjet | 113 | 12/03/2020 |

| Air France-KLM | 81 | 12/03/2020 |

| Turkish Airlines | 68 | 31/12/2019 |

| Lufthansa Group | 51 | 13/03/2020 |

| SAS | 51 | 31/01/2020 |

| Norwegian | 26 | 31/12/2019 |

Source: Adapted from (CAPA Centre for Aviation 2020)

Indicators of Importance of Tourism to Italy

| Variable | Italy |

| Jobs | 714,000 |

| GDP supported by air transported and by foreign tourists arriving by air | 2.7% |

| Contribution to GDP (US$ billion) | 51 |

| Foreign Direct Investment (US$ billion) | 413 |

| Exports (US$ billion) | 606 |

| Foreign Tourist Expenditure (US$ billion) | 44 |

| City pairs direct service in the top 10 countries by passenger numbers | 717 |

| International Destinations Served | 317 |

| Landing and Takeoffs (million) | 1.3 |

Source: (ATAG 2018) (IATA 2019a) and (IATA 2019b).

Connectivity Indexes for Italy

| Index | Italy | First European | Source |

| OAG | FCO – 34th | LHR – 1st | (OAG 2019) |

| ICAO Air Transport Bureau 2016 | 12 | Spain – 1 | (ATAG 2018) |

| IATA airport connectivity indicator | 4 (616.58k) | UK (901.36k) | (IATA 2018) |

Source: (OAG 2019)

Top 20 International City Pairs by Passenger Jet Seats Flown

| Week 38 2020 | Week 38 2019 | ||

| # | City Pair | # | City Pair |

| 1 | Antalya TR – Moscou RU | 1 | Hong Kong HK – Taipei TW |

| 2 | Faro PT – London GB | 2 | Seoul KR – Tokyo JP |

| 3 | Istanbul TR – London GB | 3 | Dublin IE – London GB |

| 4 | Istanbul TR – Moscou RU | 4 | Jakarta ID – Singapore SG |

| 5 | London GB – Milan IT | 5 | Kuala Lumpur MY – Singapore SG |

| 6 | Doha QA – London GB | 6 | Amsterdan NL – London GB |

| 7 | Athens GR – London GB | 7 | Bangkok TH – Hongkong HK |

| 8 | Dublin IE – London GB | 8 | Taipei TW – Tokyo JP |

| 9 | Lisbon PT – London GB | 9 | Bangkok TH – Hong Kong HK |

| 10 | Hong Kong HK – Taipei TW | 10 | London GB – New York US |

| 11 | Chicago US – Tokyo JP | 11 | Hong Kong HK – Tokyo JP |

| 12 | Dubai AE – London GB | 12 | Hong Kong HK – Shanghai CN |

| 13 | London GB – Malaga ES | 13 | Dubai AE – London GB |

| 14 | Lisbon PT – Paris FR | 14 | Bangkok TH – Tokyo JP |

| 15 | Amsterdam NL – London GB | 15 | Shanghai CN – Tokyo JP |

| 16 | Bangkok TH – Hong Kong HK | 16 | Barcelona ES – London GB |

| 17 | London GB – New York US | 17 | Jakarta ID – Kuala Lumpur MY |

| 18 | Antalya TR – Kiev UA | 18 | Bangkok TH – Kuala Lumpur MY |

| 19 | Paris FR – Porto PT | 19 | Osaka JP – Seoul KR |

| 20 | Shangai CN – Taipei TW | 20 | Bangkok TH Seoul KR |

Source: Adapted from (Cirium 2020)

Five Largest Airlines in Italy by Carried Passengers in Domestic Flights 2019

| Airline | Passengers

(millions) |

| Alitalia | 11.9 |

| Ryanair | 11.2 |

| EasyJet Europe | 2.6 |

| Volotea | 2.4 |

| Air Italy | 1.5 |

Source: (ENAC 2020)

Five Largest Airlines in Italy by Carried Passengers in International Flights 2019

| Airline | Passengers

(millions) |

| Ryanair | 28.6 |

| Alitalia | 9.9 |

| EasyJet Europe | 9.0 |

| Vueling Airlines | 5.9 |

| EasyJet UK | 5.7 |

Source: (ENAC 2020)

We are known for our strong political science writing help team. Check out some of our services:

– Political Science Assignment Writing Services

– Political Science Essay Writing Services

– Political Science Dissertation Writing Services