Medically Assisted Death

Part 1: Introduction

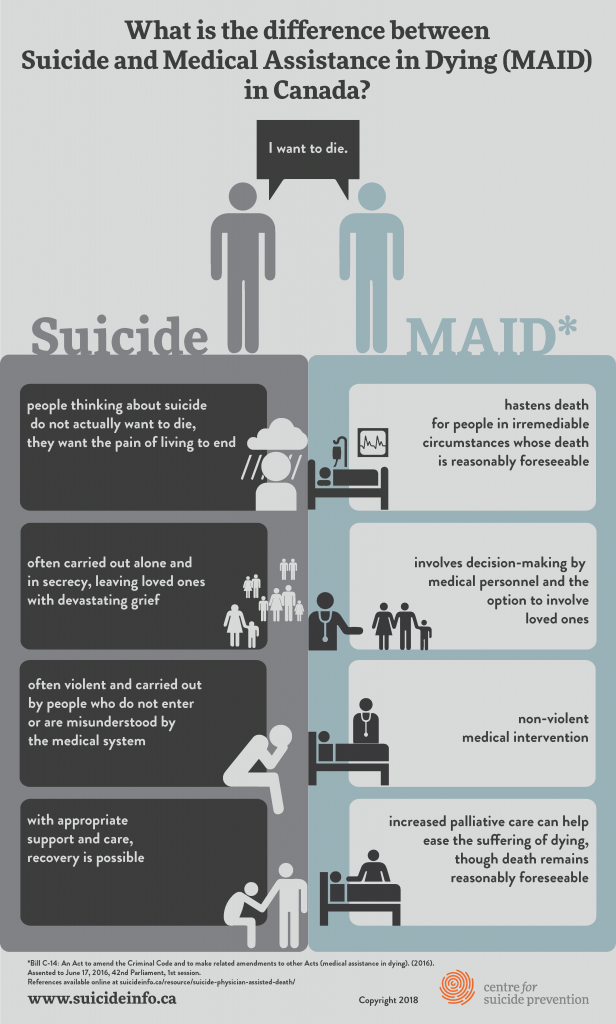

Medically assisted death legislation was introduced in Canada on 10th December 2015 and became legal in June 2016. Between then and 31st October 2018, there were 6,749 assisted deaths reported (Health Canada, 2019). It includes using medication by nurse practitioners or physicians to directly cause the death of a patient and second, provision of medication by a physician or a nurse practitioner that a patient can use to end his or her life (Health Canada, 2020). The Trudeau government has proposed several changes that are meant to update the MAiD law, which is extending the services to patients who are facing reasonably foreseeable natural death. This means that the criteria for accessing the MAiD services will be expanded to the people who are facing irremediable and grievous medical conditions and will bring new safeguards for the process with it. This paper will look into the current legislation and the requirements for MAiD in Canada and will argue own stance on the issue based on an ethical rationale and within the provincial and national standards with regards to MAiD.

Part 2: Understanding MAiD; Current and Proposed Changes

At the beginning of this year, the Canadian government consulted people on the MAiD law, where people filled a survey. They also consulted stakeholders and experts between January and February 2020. Assisted dying happens when a doctor or a physician or a nurse, at the request of the patient, causes the person’s death or getting medication from a physician or a nurse practitioner at the request and using the medication to cause own death. The MAiD law has conditions that one must meet in order to be considered for the services and safeguards in that law to ensure that it is used properly (Silvius, Memon, & Arain, 2019). Before providing MAiD, the health professionals must follow those guidelines, ensure that the person who is requesting it knows what it means, and ensure that their consent is given freely. The issues that were being considered are in line with the issue of people under the age of 18 who are able to understand what they are asking for, the issue of the advance request for patients who do not want the assistance at the moment but later they may want it and the issue of the request for the people who have a mental illness (Council of Canadian Academies. Expert Panel Working Group on Advance Requests for MAID, 2018; CAN, 2017b). The changes are based on the review that is supposed to happen after five years of legislation where the people are given an opportunity to say what they think and changes that should be made.

To be eligible for MAiD, the person must be 18 years and older since they can fully understand what they are asking for and the treatment that is being offered to them. The person must of be capable of making their own healthcare decisions; he or she must have an irredeemable or grievous medical condition, which means that; the illness or the condition must be serious and incurable; the patient is in an advanced state of an irreversible decline in their capabilities and is enduring psychological and physical suffering that is caused by the medical condition or that state of decline which is intolerable by the person, and the person natural death is reasonably foreseeable (CNA, 2017b). The patient must also make a voluntary request and provide informed consent to MAiD after he/she is informed of available means to relieve their suffering, which includes palliative care (Council of Canadian Academies. Expert Panel Working Group on Advance Requests for MAID, 2018). To be offered MAiD, there ought to be a witness who is 18 years and older, and two nurse practitioners or independent physicians must confirm that the patients meet the requirements for eligibility. The assistance cannot be provided until ten days after the patient has made a request for it unless a nurse or physician declares it imminent to provide it within a shorter waiting period.

Part 3: Stating and Supporting Stance

MAiD helps reduce the amount and duration of suffering for a patient who would otherwise die a natural death. For this reason, I support MAiD and the expansion of legislation that will allow it to be carried under advanced requests as no one knows when he/she can get too sick to make a decision. This reduces suffering for the family and the person in case that happens. From the utilitarian perspective, murder can be justified when benefits outweigh its cost. It argues that the aggregate welfare which should be maximized and suffering should be minimized. In this case, the end justifies the mean, and it is based on a motivation to do no harm (Mckinnon & Fiala, 2009). MAiD is for a good cause, and in the end, the sufferings of the individuals are reduced, and he pr she is able to die with dignity. Assisted death will also help the patient make some decisions about how he wants to go and when and hence reduce the amount of pressure on the patient and the family. Natural death can be slow and anguishing, and it is more reasonable and humane to want to reduce this pain, and especially when death is inevitable. Nonetheless, when we let incapacitated people and who are in anguish continue to live against their wish until they die naturally, we will do more harm than good. This is because, at the end of the day, the patient will not get better, and living with that knowledge is emotional torture for the client and his family. Secondly, not offering MAiD to the patient who requires a lot of support to live awaiting natural death will also consume more healthcare fund that could be used to treat those who have a hope of recovery. The denial may also make space for the people who may have a chance to live but die because of lack of that hospital space. At the end of the day, MAiD ought to be advanced since it does better than harm in the long run. The CNO ethical standards state that nurses should promote the client’s well-being, which means that their welfare and health should be promoted and by removing or preventing harm, especially when it is impeding, giving clients a choice to end their life will improve their well-being by reducing suffering. The clients also have a choice, and this choice should be informed for them to make a decision whether to refuse or accept care; when the patients refuse care and ask for MAiD, they should be given full information, and if they choose to go through with it, their decision should be respected, and after ten days, where applicable, their choices should be met. Nurses should also respect life, which means that patients’ lives should be treated with consideration, respected, and protected (CNO, 2018a). Life is precious, and one should be allowed to lead a quality life, and when it seizes to be quality, they should be offered a dignified death if that will preserve the dignity of their life (CNO, 2018a).

Part 4: Own Involvement

When a patient loses the ability to make decisions, and an advanced request for MAiD has been made, there is a need for it to be acted upon by the medical practitioners. Under the current legislation, it is a must give the patients an opportunity to withdraw their request and make sure that the client gives an express consent to receive MAiD and those who cannot give express consent or those without a decision-making capacity are not eligible for MAiD. Before granting a patient MAiD, they must meet the eligibility criteria illness (Council of Canadian Academies. Expert Panel Working Group on Advance Requests for MAID, 2018). Based on the prior directive, providing MAiD when patients lack the capacity to consent will make the nurse be in violation of the criminal code. As a nurse, there is a need to review the formal advanced directives made by the patient on their care preference if they are incapacitated and cannot make the decision. The nurse should also be there, offering the information that the patient needs to make a decision about their care and give them clear information that will guide their care. There is also a non-emergency decision making in healthcare when the person does not have the ability to make informed consent under the law (CNA, 2017b). As a nurse, there is a need to have full knowledge of the flow of information and the inquiry to make, and the course of action to take based on if the person had signed an advanced directive. The nurses should also consult the family members before going ahead and making a decision to offer MAiD.

In cases where the patient had been approved for MAiD but became unable to make decisions before the expiry of 10 days to confirm, it is vital to ensure that all safeguards had been met. All the specified documents that are related to the criminal code for the provision of MAiD should be maintained. In addition to that, it is necessary to find someone who is related to the patient, over 18 years and understands the nature of MAiD to sign the request in the presence of the patient and on behalf of the patient (CAN, 2017b). After reaching a consensus, arrangements should be made in order to reduce potential stress on family and unnecessary delays.

Conclusion

MAiD was made into legislation in June 2016, and since then, there have been over 6000 assisted suicides. Being the 5th year after the law is being reviewed for changes and improvements. MAiD is more accommodating to patients, and it does better than harm to them. This is because it allows patients to make decisions on how they want to die, and when and when this happens, they are able to reduce their sufferings, especially when death is inevitable. Nurses should make sure that the patient has all the information he/she needs prior to making a decision to receive MAiD. After requesting MAiD, there should be ten days waiting period for the patient to confirm that he/she still wants assisted dying according to the law. However, a patient may become incapacitated before the expiry of 10 days; in that case, the healthcare practitioners should make a decision based on the patient’s information and if he/she had signed an advanced request for MAiD. All decisions surrounding medically assisted death should be made within Canadian law.