Abstract

This dissertation describes food safety perceptions and self-recognised information needs of Food Safety Public Health Inspectors (FS-PHIs) in Hail, Saudi Arabia, between February and March 2015. A quantitative investigation approach using a cross-sectional survey of 56 FS-PHIs was employed for data collection and the response rate was 80%. Among the municipalities in Hail, the highest proportions (58.9%) of participants were from Middle municipality, 21.4% from North municipality and the rest (19%) from South municipality. The majority of the respondents were between age group 18-39 years (~90%). Furthermore, approximately 60% of the FS-PHIs hold secondary and diploma level degrees. The maximum percentages (41%) of respondents were with 5-9.9 years of experiences. About the perceptions, the majority of participants (96%) reported confidence with their current knowledge of proper hand washing, cleaning and sanitising of utensils and equipment (89%) and proper storage of food (89%). However, the majority of participants were ‘neither confident nor unconfident’ with their knowledge of food-borne pathogens, vermin and food pests (32.1%), specialty foods (37.5%) and cross-contamination (30.4%). The Arabic language was the first choice of languages for food safety resources (82%), followed by English (48%) and Urdu (45%). They indicated the need for computer facilities, online resources for food safety information, resources in additional languages, additional food safety information on specialty foods, ongoing food safety education and training for FS-PHIs. No statistical significant association (P-value > 0.05) was found between the demographic variables with the research questions of this study. The FS-PHIs engaged in taking care of food safety can be benefitted from the data collected for this study specially in case of developing information resources.

ii

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the QUT Human Research Ethics Committee Approval number 1400000977 (See Appendix 1).

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE RESEARCH

Food safety is emerging as a crucial concern in most parts of world, as it can significantly affect food security, nutritional status and the sustainable development of any country (Elmi, 2004; UNIDO, 2012). It is a continuing public health dilemma as antibiotic resistance can result in the emergence of broad-spectrum foodborne pathogens. Continuously updated interventions and control strategies are required to evade potentially serious health hazards (CDC, 2011; Jahan, 2012; Tauxe, 2002). The recent increase in the incidence of foodborne illnesses (FBIs) around the world suggests that food safety is an important issue that needs immediate intervention. It has negative implications for public health as well as international trade (Floros, 2010). Although many awareness campaigns and initiatives have been launched by World Health Organisation (WHO) in the past about food safety, the issue still looms around the globe (Timmer, 2012). The awareness of food safety needs varies between countries, along with access to food science, detection technologies, identification of food safety risk factors, protocols and risk mitigation strategies (Newell et al., 2010).In addition, there is a serious emphasis in Saudi Arabia (KSA) on the necessity to eat Halal food that has been prepared in compliance with Islamic religious law.

The safety and quality of food has a tremendous effect on public health and this has been a major concern for years, due to the constant presence of potentially lethal FBI. The supply of safe food to the consumer decreases the risk of FBI, and can therefore reduce the rates of illness and mortality. FBI can have a negative impact on the economy in many different forms. One example is financial loss from food bans and recalls, but also in terms of lost productivity when people are sick and not working. In fact, a study undertaken in Australia prepared for the Australian Government Department of Health and Aging by Applied Economics Pty Ltd shows that productivity and lifestyle costs were by far the largest costs of food borne disease in Australia (Abelson, Forbes & Hall, 2006). Additionally, there are also costs incurred in the treatment of affected people (FAO, 2006).

1.1.1 Hail region–Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

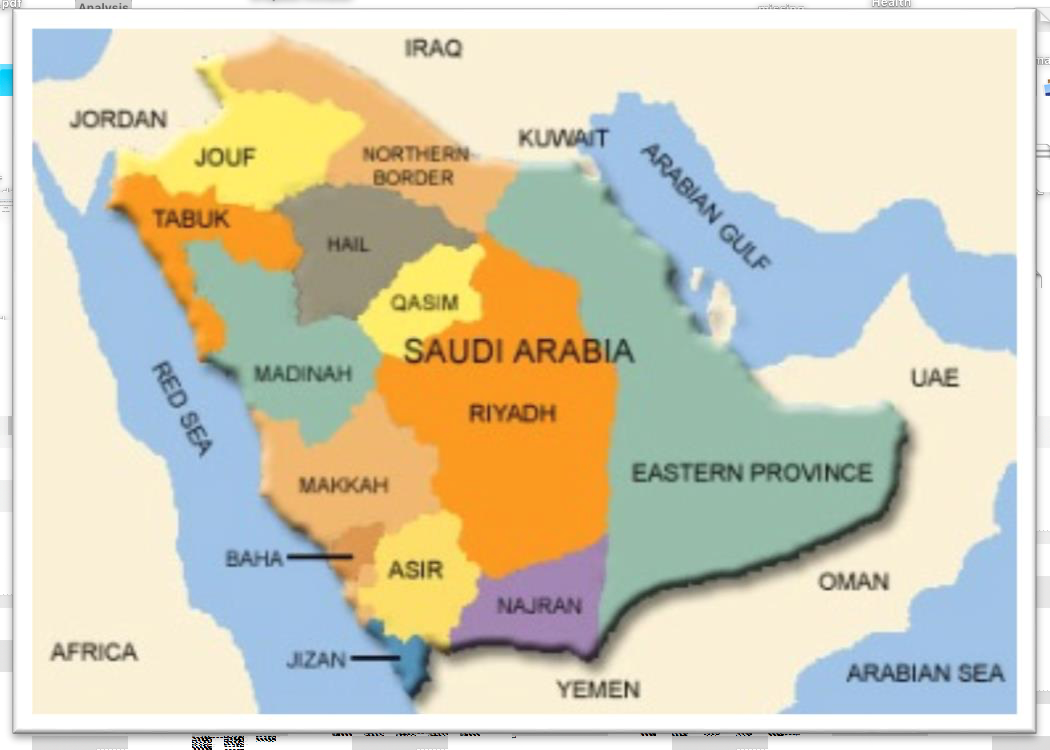

KSA is the southwest cornered country of Asia with the Red Sea, Yemen, United Arab Emirates, the Arabian Gulf and Jordan on the borders. The overall population of KSA is approximately 29 million (CDSI, 2010). The weather of KSA is basically hot and dry in summer and the reverse in winter. Hail city (capital of the Hail province) is located in the northern region of Saudi Arabia with a population of over 527,000. Hail has both dry and fertile types of land, which allow it to produce several types of crops. For example, the region produces food such as barley, corn, vegetable, dates, citrus etc (Asiry, Hassan & AlRashidi, 2013).

Figure 1-1. A map of KSA Hail region (Asiry, Hassan & AlRashidi, 2013) 1.1.2 Objectiveandtheresearchquestions

The main objective of this research was to explore the perceptions and self- recognised needs of Food Safety Public Health Inspectors (FS-PHIs) in Hail Region of Saudi Arabia through the effective use of quantitative research. In order to further investigate this topic, it was necessary to identify a questionnaire to be adapted to the context of Saudi Arabia to obtain the appropriate data and meet the objective.

The first step in evidence-based research is to define a clear, focused and answerable research question. In this case, the research questions are based on the PICO format Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes (Adams et al., 2009). The population is Food Safety Public Health Inspectors (FS-PHIs) in Hail Region. While there is no intervention or comparison, the measured outcome includes detecting the perceived risk level and knowledge of FS-PHIs, and their need for resources and knowledge regarding food safety.

Chapter 1:Introduction 3

1.2

- What are the important factors to consider in food safety according to public health inspectors in Hail?

How confident are the public health inspectors in their knowledge of food safety issues and food pathogens?

How concerned are the public health inspectors in regard to the various types of food pathogens?

What type of resources would the public health inspectors be most likely to access if they needed food safety information?

How useful are the various information resources that are currently available to public health inspectors in Hail?

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Research questions include:

There is an increasing in the incidence of food poisoning outbreaks in KSA (Al-Mazrou, 2004; Ministry of Health, 2002). This increase has prompted the need for scientific research-based strategic actions to tackle the alarming situation. Unfortunately, no evidence-building studies have been conducted in KSA to help to plan and effectively implement corrective measures regarding food safety issues. Moreover, evidence is currently lacking on the usefulness of the various types of resources from the perspective of a Food Safety Inspector.

In previous surveys of Canadian Public Health Inspectors (PHIs) by Pham et al. (2010, 2012), the perceptions and needs of the public health inspectors were explored. The present study seeks to use the report of Pham et al. as a model or a template in order to understand the perceptions and needs of Public Health Inspectors as they oversee food

4 Chapter 1:Introduction

safety in KSA. This study of the perceptions and self-recognised needs of FS-PHIs in KSA (i.e. educational trainings/workshops, types of information resources, online assistance, language, etc.), gives special reference to food-safety monitoring and inspection. The Canadian and Saudi examples have some differences regarding the needs of FS-PHIs. For instance, Canada has language considerations (English and French) while in Hail the Arabic language is the first language spoken followed by English and some other foreign languages spoken by a minority of people. There are also numerous other different factors (e.g. the agricultural sector, the types of foods consumed, religious influence, etc.) that need to be considered in making any assumptions and suggestions regarding food safety. The researcher considered these special circumstances while designing the tools of this study.

1.2.1 The incidence of foodborne illnesses

Food contamination by agents (e.g. bacteria, viruses and toxins) can often cause illness when ingested into the body. FBIs are becoming increasingly common, and more than 1.8 million people around the world were documented to have died as result of diarrheal diseases in 2005 alone (Newell et al., 2010). Contaminated food and water were responsible for the majority of these reported cases (Newell et al., 2010), therefore it is important that public health efforts be implemented to reduce the burden of disease through the routine monitoring of FBIs and by the application of a ‘farm-to-fork’ approach. Altering levels of FBIS can be monitored using baseline surveillance data (Newell et al., 2010).

Food safety control systems are very important and special consideration is required to tackle the increasing burden of FBIs. A steady increase in the number of food poisoning in KSA (from 186 to 482) was observed between 1990 and 2000 (Ministry of Health, 2002). However, caution needs to be taken in regards to the interpretation of these results since the number of reported cases is dependant on the occurrence of cases as well as the efficiency of reporting system. Therefore, it is hard to ascertain whether the observed trend has resulted from a real increase in food poisoning outbreaks or whether in part it is a reflection of an improved reporting system (Al-Mazrou, 2004). This increased occurrence of food poisoning outbreaks was mainly observed during the summer (from June to August) and the Hajj season, as vacationers and visitors purchased more food from restaurants across the community (Al-Mazrou, 2004). It has been argued that this spike in cases can be explained by the fact that visitors coming from various countries which have different cultures, lifestyles and socio-economic status are exposed to food outlets that are crowded and have compromised food hygiene standards and foodborne pathogens which may be non-existent or very rare in their home country (Al-Mazrou, 2004; Jahan, 2012). Various contributing factors, including a hot climate (that provides favourable conditions for the growth of the opportunistic pathogenic bacteria), inadequate knowledge of food safety among food handlers, and inappropriate inspection and monitoring can increase the risk of FBIs or outbreaks in the community (Al-Mazrou, 2004; Jahan, 2012). In 2006, KSA recorded 31 FBIs leading to the reporting of 231 cases. Out of these 231 reported cases, men constituted 67%, and 68% were adults. The most common causative agent was Salmonella followed by Staphylococcus aureus. Chicken meat was the main causative food, being responsible for 68% of foodborne poisoning. FBIs reported during Hajj include diarrhea and cholera (Al-Goblan &Jahan,2010; Al-Tawfiq & Memish, 2012; Al-Mazrou, 2004). Similarly, the emergence of foodborne pathogens such as E.coli and the Norovirus has added more concerns to food and health departments (Al-Mazrou, 2004). Multi-drug resistant strains of bacteria (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus) have also been reported in food products from Makah in KSA (Abulreesh & Organji, 2011). Similarly, Salmonella outbreaks at cultural functions demand an effective method to control FBIs. The role of the food inspector in controlling such issues needs to be addressed (Aljoudi et al., 2010).

1.2.2 The current food control systems in KSA

In KSA there are approximately 2700 FS-PHIs working for the department of Environmental Health, which falls under the MOMRA (F. Emmad, personal communication, May 10, 2015). In addition to this, there are other FS-PHIs who work for other authorities such as the Ministry of Commerce (MOC), the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA), Ministry of Agriculture (MOA) and the Ministry of Health (MOH). However, there is insufficient information available about these FS-PHIs.

In terms of training, a program of food safety is run by the Technical and Vocational Training Corporation (TVTC). TVTC is a governmental agency with the responsibility for vocational education and training in the KSA. Prior to 2005, the educational prerequisite to be a FS-PHI was the attainment of a secondary diploma. This was changed in 2005 when the program was expanded to include a two-year diploma which was completed after secondary school, making it the current educational requirement to become a FS-PHI (TVTC, 2015).

KSA has introduced measures to strengthen its food control systems (FCS) to cope with these trends. The Ministry of Municipalities and Rural Affairs (MOMRA) produced more than 80 brochures on food regulation, services, trade and production in order to reduce FBIs and prevent fraudulent practices (MOMRA, 2011b). Other bodies, including the MOC, SFDA, MOH and MOA, also have responsibilities in ensuring food safety and quality. MOMRA (2014) outlines that the General Department of Environmental Health was established in 1975 under the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs, and is responsible for ensuring food safety throughout KSA. Food safety relies on appropriate care being taken at all levels of food production value chain from the primary producer to the wholesalers, retailers and customers. The assessments and audits carried out by FS-PHIs are important in managing food safety across all of these segments of the food production industry. It is generally recognised that there are insufficient qualified specialists in the field of food safety, where inadequate evaluation, monitoring and control contributing to the increased incidence of FBIs (Al-Kandari & Jukes 2009; Pham et al., 2012; Pham et al., 2010b).

1.2.3 The importance of having an effective national food control system (NFCS)

Ensuring the safety of food is necessary if people are to maintain health and prevent diseases being transmitted by food in developed countries as well as developing countries. A NFCS has specific goals (e.g. providing consumers with assurance against the risk of food diseases, protecting them against fraudulent practices and falsification, and contributing to economic development through maintenance of consumer confidence), which then flow through to consumer expenditure and investment (FAO, 2006). An effective and efficient NFCS will be required if KSA is to achieve this goal. KSA will need to ensure the safety of food, and to reduce the risk of or prevent illnesses. NFCS ensure that quality products meet consumer expectations, protecting the consumer from deceptive and fraudulent practices. Whitehead (1995) argues that there are major opportunities for both national and international trade resulting from the establishment of a well-organised and structured NFCS. Some countries, however, have weaker food control standards and health inspection systems and can’t provide food standards high enough to make consumption safe or to meet international sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) requirements for the food.

2.1 INTRODUCTION

Food is a fundamental and essential requirement for people to sustain life and nutritional health, but consuming food contaminated with dangerous bacteria and other microorganisms can pose a serious threat to public health. Numerous factors contribute to the potential hazards in food including improper agricultural practices, improper hygiene practices in the food supply chain, inadequate preventive controls during food processing, adulteration (e.g. as a result of the abuse of chemicals), cross-contamination and improper storage (Institute of Medicine (USA), 2012; Institute of Medicine (USA), 2006). Microorganisms, heavy metals, insecticides, veterinary drugs are considered to be the main threats to human health. Despite efforts undertaken by various institutions and organisations involved in food safety, contaminated food is a serious problem. Therefore, an effective FCS is very important for the reduction of the incidence of diseases. This also impacts on the improvement of economic growth resulting from increased international trade.

Bubshait et al. (2000) found that approximately 113 patients in the eastern region of KSA had gastroenteritis (via Vibrio cholera from drinking contaminated water) each year. This number of people equates to 6 per 100,000 people per annum (Bubshait et al., 2000). Another study, undertaken by Ahmed et al. (2006) during the Hajj season in KSA, showed that the most frequent food poisoning cases in the hospital were gastroenteritis with a frequency of 4.4 per 10,000 people annually as a result of food contamination. However, the low quality of food control and monitoring system performance by authorities is considered the likely cause of poor hygienic practices and foodborne diseases (Hopper & Boutrif, 2006).

The monitoring and reporting systems for food poisoning need to consider the true situation of what is actually occurring. The systems for the reporting of food poisoning incidences in KSA are not as stringent or reliable as in Australia or other developed countries. For example, Australian government developed a collaborative initiative and has created a webpage named “OzFoodNet”, established in 2000, which is the collection of information (causes and incidences) of all FBIs in Australia (Al-Mazrou, 2004; OzFoodNet Working Group, 2012).

Similar to some other countries, a large amount of food poisoning cases are never reported to the health system in KSA (Al-Mazrou, 2004; Hayajneh, 2015). Food poisoning is seriously under reported in KSA with only approximately 5000 food poisoning cases reported annually. In 2008, comments from the SFDA president indicate that this figure was not a true representation of the number of food poisoning cases in KSA, and reinforced that the comparative number of food poisoning incidences in Australia (with a similar population) were more than 4 million per year (Alkanhal, 2008).

Food safety training of those who handle food was shown to have a positive impact on reducing the bad practices and mishandling of food. Chanda et al. (2010) stated that the FCS can realise many of the objectives by training employees involved in the management of food, food law, food control, legislation and auditing, laboratories, food and information, education, and communication (IEC) (Chanda et al., 2010).

2.2 ELEMENTS OF AN EFFECTIVE FOOD CONTROL SYSTEM

Whitehead (1995) and (Hopper & Boutrif, 2007) both proposed that a well-structured and effective NFCS was very important in ensuring safe food that is fit for human consumption and meets consumer expectations in regards to protection against fraudulent practices. In order to be well structured and effective, the NFCS should consist of a number of fundamental elements including a clear and well-defined role for food control management and a significant mechanism for communication and coordination between different authorities (Hopper & Boutrif, 2007; Whitehead, 1995). In terms of food control, the NFCS should confirm that food is produced, processed, handled, stored and dispatched in compliance with legal requirements, even if it is carried out by a single institution or multiple agencies (Whitehead, 1995). Linko and Linko (1998) proposed that an effective control system should have an intelligent management system to save records and exchange information between related organisations, as well as food control technologies using electronic devices (Linko & Linko, 1998). These control systems are based on a model that can help organisations and professionals conduct research based on the analysis of information.

2.3 PROCESS TO ASSESS CAPACITY BUILDING NEEDS

Different processes must be implemented in order to assess the need for capacity building of an NFCS. According to Hopper and Boutrif (2007), an NFCS can be strengthened by using a process (e.g. analysis of the situation) to identify potential targets, objectives and priorities for immediate action. Figure 2-1 shows a schematic of processes that have been adopted by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the guidelines for evaluating the need for capacity building (Hopper & Boutrif, 2007).

Chapter 2:Literature Review 11

Step 1: Agree with stakeholders about the goals and objectives of the assessment

Step 2: Analyze the existing NFCS to assess capacity and performance

Step 3: Develop a new NFCS

Step 4: Identify and prioritize capacity building needs

Step 5: Develop an effective plan

Figure 2-1. Process steps to assess capacity building needs of NFCS (FAO, 2007)

2.4 ASSESSING FOOD CONTROL MANAGEMENT

The FAO, WHO and other scientists, have defined food control management as “a well-structured process of organising, planning, coordinating, monitoring and communicating decisions and actions for food safety and quality assurance of the food that is produced, processed and handled domestically as well as having a fluent operational coordination and apparent policy at the national level”(Al-Kandari & Jukes, 2009; Anyanwu & Jukes, 1990; Whitehead, 1995). However, the FCS in the KSA is managed across several authorities and agencies such as the MOMRA, MOA, MOH, SFDA and MOC. Figure 2-2 shows the authorities involved in food safety in KSA.

12 Chapter 2:Literature Review

Figure 2-2. Authorities involved in food safety in KSA. The main responsibility of food safety assurance (including inspection, recalling and penalising the violating establishments) lies with the FS-PHIs of the municipal authority because of the low perceived importance of the other authorities (e.g. the agricultural sector) (Al-Kandari & Jukes, 2009). The distribution of food control responsibilities is shared among several authorities within the country, which may lead to an overlap of duties as a result of making a decision on the same matter by different departments (Al-Kandari & Jukes, 2009). There are other disadvantages in this system, such as a lack of informational flow between the authorities that would help these organisations to evaluate and develop the food control system.

KSA established the SFDA in 2003, with a commitment to improve the current FCS as well as undertake other important duties related to food and drugs. One of the main tasks of the SFDA is the revision and modification of the current regulatory laws with the objective of making them more efficient and accurate in terms of food safety and quality assurance. It also has the role of inspecting health establishments in order to ensure that these establishments have implemented the rules and safety regulations. In addition, the SDFA has launched and issued specifications and standards, as well as special stipulations that have been adopted and harmonised with international standards (SFDA, 2011).

2.5 ASSESSING FOOD LEGISLATION

Food law can be defined as a legal text, which contains a number of principles of food control in the country, involving different concepts of food production, handling, processing and distribution, and includes detailed procedures for food control (Hopper & Boutrif, 2007). It is regarded as the foundation of the FCS and is the expression of a decision on governments to ensure food quality and safety. It specifies the procedures and methods of application of the law, including the right to enforce the laws and rules that ensure food safety. In addition, it describes the functions of the agencies, authorities and government organisations specifying the responsibilities of the various authorities, and also explaining the procedure to applicants to restrict unfair practices to the consumer (Whitehead, 1995). The continuous assessment and enforceable provisions of a modern FCS are provided by the FAO. This protects consumers against FBIs by ensuring that food is safe to eat, and creates the principle that fair trade of foods alleviates and prevents the occurrence of abuse.

It has been suggested by Whitehead (1995) that food law should be simple and clear in order to be applied by the food manufacturer and handler (Whitehead, 1995). Complicated and ambiguous laws and legislation may prevent the food handler from applying the rules. According to the FAO, a single food control law is more effective than multiple laws to avoid confliction and overlapping of administering these rules between authorities (FAO, 1986). In KSA, the food control law tends to be distributed across multiple authorities. These authorities share some of the regulations and rules. Al-Kandari and Jukes (2009) concluded that one of the main obstructions facing the Gulf Countries Cooperation (GCC), where KSA is a member, is the distribution of responsibilities across several authorities (Al-Kandari and Jukes, 2009).

2.6 ASSESSING FOOD INSPECTION

Hopper and Boutrif (2006) defines food inspection as “inspection of the food that is locally produced or imported in order to verify that the food has been processed, manufactured, prepared, stored, handled, transported and marketed in compliance with the requirement of national food control laws and legislation” (Hopper & Boutrif, 2007). While the inspection of food in KSA is managed by different departments and agencies, MOMRA is the main body that is responsible for the control of food, especially foods that are processed in the country. The Department of Environmental Health in the various municipalities is required to check imported and local processed food, banning and/or recalling food if necessary. Furthermore, the Department monitors the slaughter of animals in slaughterhouses and performs an autopsy inspection of animal carcasses after the slaughter process is complete (Municipality, 2011). Al-Kandari and Jukes (2009) indicated that food inspection in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) occurs mainly through physical inspection and through laboratory analysis. The FAO/WHO (2005) in the regional meeting paper (which was conducted by both organisations) suggested that the inspection carried out by the majority of GCC authorities is an example of a classic food inspection role where inspectors visited randomly selected eating and food establishments and passed judgement based on a physical inspection and personal experience. At the conclusion of the inspection, a report is prepared. These reports are submitted to relevant regulatory or administrative bodies but do not appear to be collated into a true and comprehensive assessment of food safety (FAO/WHO, 2005).

2.7 ASSESSING A FOOD CONTROL LABORATORY

If the country engages in international trade with food imports, it becomes imperative to establish food laboratories (an essential element in the food control system). The physical inspection conducted by the FS-PHIs will not detect certain bacteria or harmful agents. For a more thorough analysis, a food laboratory is required in order to assist FS- PHIs to perform their duties well and eventually to prevent FBIs and food poisoning. However, for a food laboratory to be effective in achieving these aims, certain requirements (listed in the FAO documents on strengthening the NFCS) need to be met. For example, one of these requirements is the necessity to establish a team to manage the capacity building needs assessment process, followed by the need for defining the scope of the capacity building needs assessment (Hopper & Boutrif, 2006). Food analysis (which includes control over the composition), detection and analysis of contaminants, and nutritional value are very necessary in order to protect consumers against adulteration and FBIs. The importance of food laboratories is illustrated and it is outlined that they are responsible for the identification, detection and estimation of contaminants in food. These may include heavy metals, carcinogens and pesticides (Hopper & Boutrif, 2006).

2.8 OFFICIAL FOOD CONTROL LABORATORIES

In addition to the food grown and prepared within KSA, the quality and safety of imported food is also important. FS-PHIs also have the responsibility for the monitoring of imported foods. KSA has 10 laboratories located at its ports. The responsibility of these laboratories is to analyse and control imported food. The management of these laboratories falls under SFDA. The laboratories have the responsibility for carrying out the following duties:

- Analysis of food for chemical contamination (e.g. pesticide, food additives and carcinogens).

- Sampling/analysis of food for microbial contamination.

- Inspection of food for the quality assurance of the products and the prevention of adulteration.

Prior to the establishment of SFDA in 2003, these laboratories were controlled by the MOC (MOH, 2011).

2.9 ASSESSING INFORMATION, EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION (IEC)

The FAO (2007) describes the IEC as an important element of the FCS, which increases awareness and understanding of entities that are concerned about food safety. Food authorities may use the IEC in order to teach consumers about the safety and quality of food as well as encouraging food manufacturers to apply programs such as Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), procedures for Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), Standard Operational Procedures (SOP) and Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures (SSOP) (Hopper & Boutrif, 2007). The training of FS-PHIs to broaden their knowledge about food safety is highly recommended in order to help them to conduct research on food safety and improve quality control. It can be useful in improving communication skills, especially English, because most of the food handlers in KSA are from overseas and Arabic is not their mother tongue (Al-Kandari & Jukes 2009). It is important that food handlers are monitored by food inspectors and made aware of their mistakes. Language becomes an important element of communication since it ensures that the food handler understands exactly where they did wrong when handling the food. Good communication of such information will help to minimise similar mistakes in the future.

2.10 KNOWLEDGE TRANSLATION (KT)

“Knowledge translation” (KT) is a relatively new term coined by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) in 2000. CIHR defined KT as “the exchange, synthesis

and ethically-sound application of knowledge – within a complex system of interactions among researchers and users – to accelerate the capture of the benefits of research for Canadians through improved health, more effective services and products, and a strengthened health care system” (CIHR, 2005).

KT consists of effective strategies that help the exchange of research results in an ethical manner using complex interactions between researchers (Armstrong et al., 2006). The concept of KT enables an acceleration of the transformation of knowledge and evidence into practice. In this case, KT is crucial in public health as it will translate the results of this study into policies and these policies will ultimately be promoted into practice. It is important that the adoption of KT be conducted through the use of practical tools, and this may require government support (Armstrong et al., 2006). However, the challenge for the implementation of KT is the ability to create a partnership between all players, especially policy-makers, researchers and food authorities, in order to promote better outcomes.

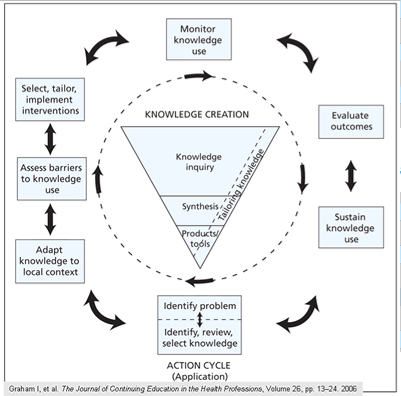

The implementation of KT should be based on a framework that comprises five stages. The first stage is building a case for action, which is the action of implementing an intervention to solve any identified problem. The second stage consists of defining the contributory factors that can facilitate the intervention and the time of implementation. The third stage is the definition of opportunities for action. The fourth stage involves an evaluation for the intervention. The fifth and final stage involves the development of appropriate policies to address the research question (Armstrong et al., 2006). Figure 2-3 describes the knowledge-to-action framework (Graham et al., 2006).

18 Chapter 2:Literature Review

Figure 2-3. “Knowledge-to-action framework” (Graham et al., 2006)

The KT model should be applicable and transferrable so the theoretical perspectives can be translated into an effective action plan. Thus, the tool should be compatible with the users – the researchers, the disseminators and the food inspectors.

This research study is in the first stage of the KT model. It seeks to build a case for action which is to identify the needs and knowledge gaps among FS-PHIs for better intervention and to improve food safety in KSA. In this case, it is essential to understand climate, culture and the religion in Saudi Arabia as it has considerable influence on food safety perception of FS-PHI’s.

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

3.1 STUDY DESIGN

A cross-sectional survey attempts to identify the frequency or level of specific characteristics in a particular population at any point in time. The advantages of this type of study are the ability to provide a good picture of the targeted population, relatively low- cost and it can be conducted in a short period of time (WHO, 2001). In addition, cross- sectional studies are good for descriptive analysis and creating hypothesis. On the other hand, the cross-sectional studies do not establish a sequence of events because a single point of time is examined and they do not always report incidences and may be susceptible to bias if there is a low response rate (WHO, 2001).

This cross-sectional study was designed to evaluate the perception of FS-PHIs regarding food safety issues, food pathogens, confidence of their knowledge and the resources needed. The response from participants was recorded as quantitative attributes and was based on a Canadian survey of public health inspectors conducted by Pham et al. (2010, 2012). A formal email was sent to the author Mai Pham for her consent. Following the receipt of written permission from her via email, the survey questionnaire was drafted in English and translated by the researcher into Arabic (the first language in KSA) to help the participants understand the questionnaire better. The researcher relied on an experienced translator in KSA to help with the translation process before the official translational office reviewed the final survey. Participation in the survey was voluntary and all responses were kept confidential. The translated form was delivered to the workplace of the FS-PHIs and distributed to each participant by the researcher in person. Each participant was requested to complete the questionnaire within one month. Reminder text messages were sent at the

second and final week of the survey. Locked boxes were placed at each municipality to collect completed questionnaires confidentially. After collecting the data, all participants were invited for an informal dinner to thank them for participation in the study. All participants were provided an opportunity to hold an open and informal exchange of views about food safety issues.

Furthermore, The STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) Statement is a reporting guideline with a checklist of 22 items that are considered necessary for good reporting of observational studies (Von Elm et al., 2007). This survey questionnaire has been compiled following the STROBE checklist for cross- sectional studies (see Appendix F).

3.2 ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS

Ethical approval was obtained from the QUT Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number 1400000977). The return of the completed survey was accepted as consent to participate in the research. No identifying personal information was acquired from individuals. Confidentiality of acquired data was assured at all times. Participant Information Sheets (PIS) with the investigators’ contact details were provided on the first page of the survey and participation was voluntary. Approval to conduct the research was obtained from Hail Municipality.

3.3 STUDY POPULATION

The research study was conducted with FS-PHIs in Hail, KSA, between February and March 2015. About seventy eligible Public Health Inspectors (PHIs) were recognised and selected from Hail region and all of them were cordially invited to participate in the study. The intention of this mission is to survey the whole FS-PHIs population of Hail and there were no specific requirements about the demographical status. However, the success of this approach also depends on the response rate. The participating FS-PHIs were distributed

within three Municipalities (i.e. Hail North, Middle and South). A comprehensive explanation of the research study and the approaches needed to respond to each question was clearly described to all the participants. Figure 3-1 shows flow chart of the eligible units and participants.

3.4.1 Demographic status

Basic demographic information (e.g. gender, age, years of experience as a FS-PHI and region) was collected through the questionnaire.

3.4.2 Importance of food safety issues

The level of perception of the importance of food safety issues was measured on a five-point scale. Responses ranged from very unimportant to very important, and there was a ‘Do not know’ or ‘No opinion’ option. The list of food safety issues comprised time- temperature abuse, cross-contamination, inadequate hand washing, and personal hygiene of food handlers, poor general housekeeping, inadequate sanitising, vermin and food pests, food from unapproved sources, speciality food, improper food storage, and a lack of food

safety knowledge by food handlers. Most of these issues were selected based on the opinion that they are considered to be the major determinants of FBIs and outbreaks by the University of Rhode Island, Food Safety Education. This system is similar to the WHO Five Keys for food safety. Furthermore, these specific issues are used in the public health inspector survey conducted in Canada (Patnoad & Hirsch, 2000; Pham et al., 2010; WHO, 2006).

3.4.3 Confidence in food safety knowledge

Participants were asked to rate their level of confidence in their knowledge about food safety issues on a five-point scale. Responses were allocated from ‘Very unconfident’ to ‘Very confident’, along with an option ‘Do not know’ or ‘No opinion’. The list of food safety issues was the same as for the previous section.

3.4.4 Concern about food pathogens

The concerns of each FS-PHI about food pathogens were evaluated on a five-point scale from ‘Very unconcerned’ to ‘Very concerned’, along with an option ‘Do not know’ or ‘No opinion’. The list of food pathogens included Salmonella, Campylobacter, E.coli0157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, Clostridium botulinum ,Clostridium perfringens, Norovirus, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus and Hepatitis A virus. The reason why these pathogens in particular have been selected is because they are most commonly reported as being the cause of food poisoning in KSA (Al-Mazrou, 2004; Aljoudi et al., 2010; ; Al-Goblan & Jahan,2010; Abulreesh & Organji, 2011). Additionally, most of them have been used in the public health inspector survey conducted in Canada (Pham et al., 2010).

3.4.5 Confidence in food pathogen knowledge

The confidence by FS-PHIs in their knowledge of food pathogens was rated on a five- point scale from ‘Very unconfident’ to ‘Very confident’. As with the previous parameters, a choice was provided for ‘Do not know’ or ‘No opinion’.

Chapter 3:Research Methodology 23

3.4.6 Information access likelihood

Participants were asked the likelihood they would access various resources if in need of food safety information. The list of resources included‘ another public health inspector’, ‘in-house resource’, ‘resource from another health unit’, ‘journal article’, ‘textbook/reference manual’, ‘unofficial websites’, ‘Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs website’. Responses were recorded on a five-point scale from ‘Very unlikely’ to ‘Very likely’, with a ‘Resource not available to me’ option.

3.4.7 Perception of information usefulness

The participants were asked to rate the usefulness of various information resources in their role as Public Health Inspectors. Responses were recorded on a five-point scale from ‘Very useless’ to ‘Very useful’. The list included regular education time/seminars/workshops, e-mail newsletter and online clearinghouses.

3.5 DATA ANALYSIS

Data entry and analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 from IBM. Descriptive statistics were used to measure the frequencies and proportions and inferential statistics was used to explore the relationships between the variables. Furthermore, associations between some demographic characteristics and some selected research questions were assessed in order to better understand the relationship among variables. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tests were employed to test the significance of the associations at the 0.05 level of significance.

Chapter 4: Results

The current study was conducted to explore the perceptions and self-recognised needs (i.e. educational trainings/workshops, types of information resources, online assistance etc.) of FS-PHIs in Hail, KSA. 56 FS-PHIs completed the survey out of 70 working in Hail, therefore the response rate was 80%. In this research, various perceptions of FS- PHIs including important factors to consider in food safety, confidence of their knowledge about food-safety issues and foodborne pathogens, and concern about food-pathogens were evaluated through cross-sectional questionnaire. Moreover, self-recognised needs such as preferred type of resources and usefulness of various information resources were also identified. The outcomes for all the parameters examined are discussed hereafter.

4.1 DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

Table 4.1 shows the demographic characteristics of the study sample. Age, education, gender, years of experiences and working place has been used as demographic variables for this study. The majority of FS-PHIs currently employed in Hail region (96.4%) are male. More than half of FS-PHIs (58.9%) were working in Middle Hail. The majority of FS-PHIs are (18-39 years old) and have worked as a FS-PHI for more than 2-years (91.1%). Most of them are Diploma holders (41.1%) followed by Bachelor qualifications (32.1%), while few FS-PHIs have postgraduate qualifications (9%).

4.2 THE IMPORTANCE OF FOOD SAFETY ISSUES

In regard to the importance of food safety, Table 4.2 shows that in the perception of FS-PHIs, various food safety issues (e.g. time-temperature abuse; inadequate hand washing; personal hygiene of food handlers; inadequate sanitising of utensils and equipment; improper food storage; and lack of food safety knowledge by food handlers and/or food premises operators) are characterised as very important, while specialty foods from different cultures are neither important nor unimportant.

4.3 CONFIDENCE OF KNOWLEDGE ABOUT FOOD SAFETY ISSUES

Table 4.3 shows that the FS-PHIs are “very confident” on knowledge about proper hand washing (57.1%), cleaning and sanitising of utensils and equipment (48.2%) and approved source of food storage (37.5%). On their knowledge about Vermin and food pests (32.1%) are ‘neither confident nor unconfident’ and Specialty foods (37.5%), whereas more FS-PHIs (30.4%) are unconfident regarding their knowledge about ‘cross-contamination’.

4.4 CONCERN ABOUT FOODBORNE PATHOGENS

Table 4.4 shows that the majority are ‘neither concerned nor unconcerned’ about Campylobacter (41.4%) C.botulinum (41.1%), C.perfringens (39.3%), E.coli 0157:H7 (41.1%), Hepatitis A virus (39.3%), Listeria (41.1%), Norovirus (41.1%) and B.cereus (46.4%), whereas a significantly higher number of FS-PHIs (51.7%) are very concerned or concerned about Salmonella.

4.5 CONFIDENCE WITH CURRENT KNOWLEDGE OF FOODBORNE PATHOGENS

Table 4.5 shows that a significant proportion of FS-PHIs are ‘neither confident nor unconfident’ and/or ‘unconfident’ with their current knowledge of foodborne pathogens as a food safety risk. Only difference can be seen in case of “Salmonella”, where 51.8% participants were more confident about their knowledge.

4.6 PREFERRED RESOURCES OF FOOD SAFETY INFORMATION

Table 4.6 shows that the majority of FS-PHIs preferred another FS-PHI (80.4%) and a textbook or reference manual (75.0%) to assess the required food safety information. However, FS-PHIs did not prefer the ‘In-house Resource’ (39.3%) as a source of information. Moreover, FS-PHIs preferred ‘unofficial websites’ (39.3%) as compared to ‘Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs website’ (3.6%) as resources for food safety information.

4.7 RANKING PREFERRED RESOURCES FOR FOOD SAFETY INFORMATION

Table 4.7 shows that about 67% (n=34) of FS-PHIs in Hail region preferred information from another FS-PHI as their first choice. Moreover, about 35% selected textbook/reference manual as second preferred resource of information. As well as, 33% chose Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs website as their third choice.

Table 4-7. Frequency and percent scores for preferred resources (ranked as top three) for food safety information

| Options

|

First Choice | Second choice | Third choice | |||

| Another public health inspector | 34 | 67

|

8 |

16 |

5

|

10

|

| In-house resource | 2 | 4

|

1 | 2 | 0

|

0

|

| Resource from another health department | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 6 |

| Journal Article | 0 | 0

|

8 |

16 |

9

|

18

|

| Textbook/reference manual | 10

|

18 | 18 | 35

|

15 | 29 |

| Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs website | 4 | 6 | 8 | 16 | 17 | 33 |

| Unofficial website | 3 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Others Resources | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 56 | 100

|

51 | 92 | 50

|

98

|

| Missing | 0 | 0

|

5 | 8 | 6

|

2

|

4.8 PREFERRED LANGUAGES FOR FOOD SAFETY INFORMATION

The language preference for food safety information resources available to food handlers and/or food premise operators was also evaluated. Most of the FS-PHIs (about 82%) made the Arabic language their first preference (Table 4.8). Moreover, about 48% of FS-PHIs selected English as second preferred language for resource information. About 45% of FS-PHIs in the Hail region chose Urdu (the national language of Pakistan) as their third choice. There were few preferences for Hindi, Bengali and Nepal’s language.

Table 4-8. Frequency and percent scores for preferred language (ranked as top three) for food safety information resources available to food handlers

| Language

|

First Choice

|

Second choice |

Third choice

|

|||

| Arabic | 43 | 82 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| English | 3 | 6 | 24 | 48 | 1 | 2 |

| Turkish | 2 | 4 | 9 | 18 | 13 | 27 |

| Hindi | 1 | 2

|

3 | 6 | 9 | 18

|

| Urdu | 4 | 8 | 11 | 22 | 22 | 45 |

| Bengali | 0 | 0

|

1 | 2 | 1 | 2

|

| Nepal | 1 | 2

|

1 | 2 | 2 | 4

|

4.9 CONFIDENCE WITH FOOD SAFETY KNOWLEDGE FOR DIFFERENT TYPES OF FOODS

Table 4.9 shows that FS-PHIs were self-confident with their knowledge about all foods (including dairy products, meat, pastry, beverage, leafy vegetables, fruits, canned food) except dried and seafood where only 19.6% of respondents felt confident.

4.10 SATISFACTION LEVEL WITH FOOD SAFETY KNOWLEDGE FOR DIFFERENT TYPES OF FOODS

The majority of FS-PHIs were ‘neither satisfied nor unsatisfied’ with the currently available information about food safety resources for almost all parameters in the foods category, except dried foods (42.9%), leafy vegetables (41.4%), pastry (41,4%) that were categorised as ‘unsatisfied’ (see Table 4.10).

4.11 FOOD SAFETY INFORMATION ABOUT UNFAMILIAR FOODS

Table 4.11 shows that the majority of FS-PHIs preferred another FS-PHI (80.4%) as a source to obtain required information on unfamiliar foods. Textbook or reference manual were observed as the second leading resource (66.1%)to obtain required information on unfamiliar foods. Interestingly, no participants (n=0%) we unlikely to use a ‘textbook/reference manual’ as a resource to get knowledge about food-safety concerns associated with unfamiliar food.

4.12 ACCESS TO COMPUTER WITH HIGH-SPEED INTERNET CONNECTIVITY AT WORKPLACE

Table 4.12 shows that about 67.9% of FS-PHIs accessed information from a computer with adequate internet-speed while the remainder did not.

An on-line resource is a convenient way for me to obtain new food safety information (n=56)

4.14 EFFECTIVE STRATEGY FOR DISSEMINATING FOOD SAFETY INFORMATION TO FS-PHIS

The perception and preferences of FS-PHIs about effective strategies for the dissemination of food safety information is presented in Table 4.14. The ‘website’ obtained the highest rating as an effective strategy for disseminating food safety information (39.3%), followed by ‘workshop/seminar’ (32.1%). Conversely, ‘web-seminar/web-cast’

Chapter 4:Results 37

(3.6%) and teleconference (7.1%) represented the least preferred strategies for disseminating information.

Table 4-14. Frequency and percent scores for effective strategy to disseminate food safety information to PHIs

| Effective strategy for disseminating food safety information | Frequency | Percent |

| Web seminar/web cast | 2 | 3.6 |

| Teleconference | 4 | 7.1 |

| Workshop/seminar | 18 | 32.1 |

| Website | 22 | 39.3 |

| E-mail newsletter | 10

|

17.9 |

| Total | 56 | 100.0 |

4.15 EFFECTIVENESS/USEFULNESS OF VARIOUS RESOURCES IN THE ROLE OF FS-PHIS

Table 4.15 shows that the majority of FS-PHIs stated that ‘seminars/workshops’ (75%) following by ‘online clearinghouse’ (55.4%) were very useful resources that support the role of FS-PHIs. The participants mentioned ‘E-mail newsletter’ as neither a useful nor a useless resource (28.6%) to improve the role of PHIs.

4.16 PREFERRED TOPICS FOR A ONE-DAY WORKSHOP

Table 4.16 shows that all FS-PHIs were interested to know all topics except ‘Issues that other inspection agencies are currently involved with’. The highest score was observed for ‘case-based outbreak scenarios’ (94.6%), while the lowest score was perceived for ‘Issues that other inspection agencies are currently involved with’ (42.9%).

4.17 THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN QUALIFICATION AND LEVEL OF CONFIDENCE ABOUT THE KNOWLEDGE OF FOODBORNE PATHOGENS

To be able to investigate any relationships between education level and confidence in knowledge of food pathogens, a new variable was created for the average confidence in knowledge of the 10 food pathogens by averaging the 10 scores in table 4.5. However, four averages could not be calculated because of missing values (when the answer was “Don’t know/ No opinion”). This resulted in a total sample size of 52 for this analysis. The dataset was divided into four different groups based on level of education: Secondary School (mean=2.28, sd=1.29, n=8), Diploma (mean=3.04, sd=1.27, n=22), Bachelor (mean=2.64, sd=1.15, n=17) and Postgraduate (mean=2.86, sd=1.17, n=5). Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) showed that the differences in mean confidences in knowledge of food pathogens were not significantly different at the 5% significance level (F (3,48)=.86, p=.47).

4.18 THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN YEARS OF EXPERIENCE AND THE IMPORTANCE LEVEL OF FOOD SAFETY ISSUES

In order to find out if there was an association between the overall importance of food safety issues and the level of experience of FS-PHIs, a new variable was created for the average importance level of food safety issues by averaging the scores for the 11 related issues from Table 4.2. To analyse the resulting average scores, the sample of 56 FS-PHIS was divided into five different groups based on years of experience: 0 to 1.9 years (mean=4.54, sd=0.3, n=5), 2 to 4.9 years (mean=4.39, sd=0.52, n=22), 5 to 9.9 years (mean=4.4, sd=0.58, n=23), 10 to 19.9 years (mean=4.65, sd=0.49, n=2) and 20 years or more (mean=4.57, sd=0.42, n=4). Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) showed that the differences in mean importance levels of food safety issues were not significantly different at the 5% significance level (F(4, 51)=.26, p=.91).

4.19 THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN FS-PHIAGE AND THE USEFULNESS LEVEL OF VARIOUS RESOURCES OF INFORMATION

To test whether the average reported usefulness of various resources in the role of FS-PHIs depended on their age, a new variable was created for the average usefulness by averaging the four scores in table 4.15. One value could not be calculated because of a missing value where the answer was “Don’t know/ No opinion”. This resulted in a total sample size of 55 for this analysis. The dataset was divided into three age groups: 18 to 29 year (mean=4.07, sd=0.55, n=24), 30 to 39 years (mean=4.23, sd=0.57, n=26) and 40 to 49 years (mean=4.6, sd=0.22, n=5). Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) showed that the differences in mean usefulness of various resources were not significantly different between the three different age groups at the 5% significance level (F(2,52)=2.1, p=.13).

Chapter 5: Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions and self-recognised needs of FS-PHIs in Hail Region of KSA through the effective use of a quantitative research approach.

There is an emerging consensus that food safety is an indispensable factor that significantly contributes to food security, nutritional status and sustainable development in any country(Elmi, 2004; UNIDO, 2012). In KSA, food safety is becoming a major public health concern because of the increasing prevalence of foodborne outbreaks and incidences (Floros, 2010). Internationally, the increasing prevalence of food safety problems have been related to an inadequate knowledge of the factors that contribute to FBIs, a lack of adequately trained professionals, and inadequate accessibility to food safety information by FS-PHIs (Pham et al., 2012). An efficient FCS is an important tool to help decrease the occurrence or prevalence of FBIs in conjunction with improving the economic growth of the country (associated with international trade). The present study, while keeping all of the facts and problems in mind, revealed the perceptions and self-recognised needs of FS-PHIs.

5.1 PRINCIPAL FINDINGS

5.1.1 Personalcharacteristics

Results showed that the majority (91.1%) of FS-PHIs have 2 years or more practice and the majority (59%) of FS-PHIs hold a diploma and secondary school qualifications. Moreover, the study found that only 32.1% of the FS-PHIs hold a Bachelor Degree (see Table 4.1). Comparing to the qualification system in Canada, the Bachelor Degree in public health or safety or environmental health is the minimum requirement to be a FS-PHI (Pham, 2012), which is absent in KSA. The qualifications and training of these personnel has a significant role in the effective implementation of and compliance with food safety standards (Kassa et al., 2010; Sliwa et al., 2010). However, the low qualifications of FS-PHIs in the Hail region demands proper training and certification courses to enhance their knowledge about food safety standards and to ensure the provision of safe food to the consumer. The diploma of health inspection degree in KSA is only available for males, and this directly affects the number of female inspectors. In this study, we found that only 2 female (3.6%) FS-PHIs are working part-time at Hail municipality. However, they are basically nurses working for the Department of Health Affairs and helping the municipal authority to inspect just the women institutions due to different cultural factors. More than half of the FS-PHIs (59%) were working in Hail Middle municipality, which is the most populated area in the Hail province.

5.1.2 FoodsafetyIssues

The majority of FS-PHIs in Hail categorised various food handling practices including time- temperature abuse (94.7%), inadequate hand washing (100%), personal hygiene of food handlers (98.3%), inadequate sanitising of utensils and equipment (93.2%), improper food storage (94.6%) and the lack of food safety knowledge by food handlers and/or food premises operators (87.5%), as very important or important (see Table 4.2). Most of these issues are in agreement with the “Fatal Five”(contaminated ingredients, temperature control, personal hygiene, cross contamination and sanitation) that are considered the major determinants of FBIs and outbreaks as defined by the University of Rhode Island, Food Safety Education (Patnoad & Hirsch, 2000; Pham et al., 2010a). These are also similar to the WHO Five Keys for food safety as presented in their Five Keys to Safer Food Manual (WHO, 2006).

The confidence of knowledge of FS-PHIs about food safety issues was measured and the majority of them were found to be confident or very confident about their knowledge. For instance, time-temperature abuse (82.2%), proper hand washing (96.4%), cleaning and sanitizing utensils and equipment (89.3%), approved sources of food (62.5%) and proper storage (89.3%) (see table 4.3).Nonetheless, the FS-PHIs rated their confidence (55.4%) about ‘cross-contamination’ (one of the “Fatal Five”) as “neither confident nor unconfident” or “unconfident” and (3.6%) as “very unconfident” which refers to lack of knowledge about the importance of cross-contamination. In

contrast to this finding, the previous survey of health inspectors conducted in Canada found a high confidence (“very confident” or “confident”) of the knowledge on Cross-contamination (Pham et al., 2012). As cross-contamination is highly associated with food safety risks and the occurrence of a number of outbreaks has been linked with cross-contamination (Evans et al., 1998; Scott, 2003), this indicates the importance of cross contamination in food safety issues and the need for more training for the FS-PHIs on this topic.

5.1.3 Foodbornepathogens

The identification of various foodborne pathogens and their toxins in food commodities is the foremost difficulty in the development of a preventive approach to reduce the rate of FBIs and outbreaks. The awareness of FS-PHIs and food-preparers of foodborne pathogens is very important if we are to ensure food-safety (McMeekin et al., 2010; Unicomb, 2009). In the present study, most of the FS-PHIs responses were ‘neither concerned nor unconcerned’ about the foodborne pathogens (41.4% for Campylobacter, 41.1% C.botulinum, 39.3% C.perfringens, 41.1% E.coli 0157:H7, 39.3% Hepatitis A virus, 41.1% Listeria, 41.1% Norovirus and 46.4% B.cereus) (see Table 4.4). This perception of FS-PHIs about foodborne pathogens is a very alarming outcome. The findings in this study are inconsistent with those in a previous study (Pham et al., 2012) where the majority of FS- PHIs stated that they were “very concerned” or “concerned” about foodborne pathogens in relation to the risk to public health. Lee and Middleton (2003) indicated that about 44,451 periodic cases of foodborne infections were associated with verotoxin-producing E.coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter, C.botulinum, Listeria, Shigella, Yersinia and Hepatitis A Virus during the period of 1997-2001 (Lee & Middleton, 2003).Ensuring microbiological food safety is very important as we seek to reduce the susceptibility to foodborne infections (Lund & O’Brien, 2011).

The confidence of the FS-PHIs from Hail was assessed to ascertain any self-recognised knowledge gaps. A significant proportion perceived themselves as ‘neither confident nor unconfident’ or ‘unconfident’ regarding their knowledge about foodborne pathogens (see Table 4.5).

The results indicate that there is a lack of knowledge by FS-PHIs on foodborne pathogens and that they felt there was a need for food safety training and workshops, as well as educational/information material. Previous studies have suggested that this lack of knowledge was associated with an increased risk of FBI. Furthermore, there was a need for more knowledge about causative agents (pathogens) and the vehicles required for implementation of food safety standards (the Committee to Ensure Safe Food from Production to Consumption, the Institute of Medicine, the Board of Agriculture, the Institute of Medicine and the National Research Council, 1998).

5.1.4 Resources of food safety information

Globalisation and advanced technologies have assisted many FS-PHIs with their access to an extensive range of food safety information resources (e.g. textbook/reference manual, training/educational videos, various organisational websites, seminars/workshops and e-mail updates) (Pham et al., 2010a). In the present study, 80.4% of participants preferred to consult with another FS-PHIs and 75% use a textbook or reference manual to obtain the required information about food safety (see Table 4.6). However, this study found a high number of FS-PHIs were unaware of pathogens, and so consulting one another is not an effective strategy because this method will result in “the blind leading the blind”. Overall, the response of FS-PHIs is consistent with the views of PHIs in Canada (Pham et al., 2010a). Moreover, a significant number of FS-PHIs prioritised different resources of information (e.g. other public health inspectors, a textbook or reference manual, and the ‘Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs’ website as their first, second and third choice, respectively) (see Table 4.7).

Furthermore, the majority of FS-PHIs preferred Arabic language as their first choice for food safety information resources available to food handlers and/or food premises operators. English was their second choice and Urdu was their third choice (see Table 4.8). Although, most of the information about food safety is widely available in English, the preference might be perceived on the basis of worker diversity and their understanding of the information. Language barriers for communication and dissemination of food safety information is considered as a significant challenge by most FS-PHIs in Canada (Pham et al., 2010a).

5.1.5 Foodsafetyknowledge

Equitable access to knowledge about food safety concerns relating to the different types of foods is important if FS-PHIs are to maintain and comply with food-safety standards (Pham et al., 2012). However, in the present study, Hail’s FS-PHIs regarded themselves as self-confident regarding their knowledge about different types of foods (including dairy product, meat, pastry, beverage, fruits and canned food), with the exception of dried food, leafy vegetables and seafood where the majority were ‘neither confident nor unconfident’ (see Table 4.9). However, the majority of FS-PHIs were ‘neither satisfied nor unsatisfied’ with the current availability of food safety information resources (see Table 4.10). Many countries have established databases for food safety comprising important information of a varieties of foods to strengthen their food safety systems (Baldi & Mantovani, 2008; Institute of Medicine (US), 2012; WHO, 2015). Conversely, FS-PHIs in this study do not have access to such databases to retrieve food safety information. Therefore, the preferred resources used by FS-PHIs to access the food safety information about unfamiliar foods were evaluated and majority (80.4%) responded that they preferred their fellow FS-PHIs as a source to access the required information. Again, this is ineffective method if the other FS-PHIs also have limited knowledge. Increasing the accessibility of additional food safety information resources will help to enhance the performance of FS-PHIs in protecting and endorsing the provision of safe food (Pham et al., 2012).

The majority (92.9%) of FS-PHIs agreed that the provision of an online resource would be a convenient way to obtain new food safety information (see Table 4.13). Availability of a computer with Internet connection is a very significant facility to retrieve online food safety information, email newsletters and databases. The majority (67.9%) of FS-PHIs in the Hail have access to computer with adequate internet-speed (see Table 4.12). FS-PHIs in Hail believed that ‘websites’ and ‘workshops

and seminars’ were effective tools for disseminating food safety information (see Table 4.14). According to Pham et al. (2010, 2012), FS-PHIs in Canada considered online resources (e.g. e-mail newsletters or online clearinghouses) as an effective approach to instantly and proficiently disseminate food safety information to FS-PHIs. The majority of FS-PHIs in Hail considered ‘seminars/workshops’ as the most useful food safety information resources followed by ‘online clearinghouse’ (e.g. a web-based database for food safety information and resources). They believed that ‘E-mail newsletter’ was neither a useful nor a useless resource to improve the function (see Table 4.15).

Furthermore, ANOVA tests were employed to test any association between the FS-PHI’s qualification and confidence level of knowledge about the food pathogens, the association between years of experience of FS-PHIs and the importance level of food safety issues, the association between FS-PHI’s age with usefulness of various resources of information. It can be concluded that there was no significant association (P-value >0.05) between the variables and these demographic characteristics (see Tables 4-17, 4-18 and 4-19).

5.2 STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

5.2.1 Strengths

This pioneer research-based scientific study has been able to identify the perceptions of FS- PHIs in Hail, KSA. The investigation received a very high level of cooperation (56 out of 70 FS-PHIs working in Hail–80% response rate) and a very high completion rate of the questions, which means that it has strong internal and external validity with negligible selection bias.

The study tools were developed based on a successful FS-PHI perception study conducted in Canada. Furthermore, modification was employed to suit the context in Hail. This process made the tools holistic for any FS-PHIs perception surveys in KSA. In addition, the study may be used as the basis for large-scale population studies to find out the perceptions and needs of FS-PHIs to improve the food safety in the whole of the KSA.

The findings of this research project will help in improving the development of resources of food safety information in the Hail region as well as advocating to the policy makers. The outcomes of this research will also offer ample opportunity to identify needs (resources and improvements required) as well as gaps (lack of resources) in the public health and food safety systems according to the perceptions of FS-PHIs at Hail, KSA. Moreover, the results will have implications on the evaluation and revision of current resources for FS-PHIs working in the Hail region. Conclusively, this intervention research study will provide a significant basis for both planning and implementation.

5.2.2 Limitations

Although this study has high external validity for the Hail region, the results of this study may not necessarily be generalised to all FS-PHIs across Saudi Arabia. Efforts were made to minimise bias by informing participants that there was no “right” or “wrong” answers and they were encouraged to agree or disagree with any comments in the discussion and in the survey. As the respondents were volunteers, participation bias might occur. There are always some general limitations with surveys that may influence responses. For example, suggested answers may prompt certain responses and participants might respond to the questions in a way that they thought would be desired by the researcher. Another limitation is that this research is related to a self-assessment of personal knowledge. The problem with this is that people don’t know what they don’t know, and this factor can have an impact on how results can be interpreted and applied.

There was insufficient data regarding the food poisoning cases in Hail region in this study and this is due to limited reported data. Another limitation of this study was the dependence on using a quantitative approach and in its descriptive nature. It was suggested that a mixed method approach, combining qualitative and quantitative research methods might be more appropriate.

5.3 UNANSWERED QUESTIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

It is suggested that future research be conducted to identify why there is a lack of confidence in the knowledge of FS-PHIs regarding foodborne pathogens. Moreover, it is essential to understand

if there are any current training courses for FS-PHIs to update their knowledge and, if so, whether these courses are designed to meet their actual needs or not. The quality of curriculum on the health inspection diploma, specifically whether it contains sufficient information about food pathogens can be analysed in future research, including assessing actual (versus self-assessed) knowledge and information needs. Finally, the relevance of the bachelor degree held by some of FS- PHIs to public health or food safety might need further study.

Chapter 6: Recommendations and Conclusion

6.1 RECOMMENDATIONS

In this chapter, future recommendations are discussed. Conclusion of the present study is also provided at the end of the chapter.

Specific recommendations include:

- The majority (67%) of FS-PHIs reported regularly accessing computers with high- speed Internet connectivity in the workplace. This supports the opportunity for web-based intervention to improve the access to information facilities. The present study recommends the development of online resources (i.e. an online clearinghouse) to distribute food safety information to FS-PHI. By utilising an online clearinghouse, FS-PHIs can search for any information related to food safety, and information can be easily updated at any time. It is suggested that the implementation of an online clearinghouse can be supported and managed by the MOMRA, MOH and SFDA to ensure the reliability of this tool.

- All participating FS-PHIs expressed an interested in ongoing food safety education training, with many (96.4%) of them reporting that they were very interested in attending food safety seminars, workshops. The design of active workshops and seminars for FS-PHIs in Hail can be under consideration to improve their knowledge that might eventually improve the food safety. A KT Model could be used as a tool to cover topics related to food safety information (g. specialty foods, case studies, food pathogen, etc.) which may help to tap the identified needs established from this study.

The evidence from the study identified that the participants were less confident (55.4%) about cross contamination (“Fatal Five”) which is an important food safety issue (Patnoad & Hirsch, 2000; Phamet al., 2010a). Therefore, it is worthwhile in the future to consider cross-contamination issue in the manuals, training or workshops arranged for the FS-PHIs.

A large percentage (66.1%) of FS-PHIs preferred textbook/manuals as their source of information. The reference manual available for FS-PHIs in KSA is called “The list of municipal fines and sanctions”. However, the most recent version of this manual was issued in 2001 by the Council of Ministers. Over the past 14 years, Municipalities were informed of all changes and new regulations to this manual through circulars. These circulars are retained in the archive but it was difficult for FS-PHIs to access them. As the manual has not been renewed as a whole since 2001, it is recommended that the circulars be combined with these rules and regulations into a document that is more conveniently accessible by health inspectors.

In this study, 30.4% of the participants reported that specialty foods from different cultures are “neither important nor unimportant” and 24.4% had no opinion about it. Specialty foods are becoming more widely available in Saudi Arabia and some actions might be taken to ensure the safety of these foods to the public. Such actions include proper handling and storage requirements for these foods and more detailed information about any associated foodborne illnesses.

Few participants mentioned about their need of technology usage for better detection of pathogens in the open-ended question. Furthermore, studies suggested for an effective FCS (electronic devices) that includes intelligence

management system and food controls technologies (Linko & Linko, 1998). Given the evidence, it is recommended to provide adequate equipment to perform the inspections correctly and also to provide the training for proper use of the equipment. Such equipment could be as follows:

o A device for the detection of the quality and validity of cooking oil. o A device that measures the temperature of food in warehouses. o A device that measures the amount of bacteria on the hands of food

handlers as well as in food containers. o A device that detects the concentration of chlorine and salt in water. o A device (pH meter) that detects the acidity of liquids, meat and cheese.

In addition, the implementation of an electronic fieldwork management system would further enhance food safety inspection, performance management and control in Hail. Currently, there is an electronic fieldwork management system available for health inspectors in Riyadh and Jeddah, but this system has not been implemented in Hail. The system is designed to provide inspectors with relevant information and the ability to record inspections and images of inspections electronically. Once the inspector completes the recordings, the information and data about the inspection site is transferred to the central system automatically. This assists others to analyse the data and the movements of the inspector and to determine the health inspectors’ location (via GPS), scheduled visits, follow-up dates and the time and duration of each visit.

There are not enough national studies that cover the needs of FS-PHIs regarding their knowledge and perception about food safety. So, the Saudi Government could take steps to conduct a workforce census and national survey similar to this study on FS-PHIs across all regions of KSA, to assist in the identification of gaps in the knowledge and skills of FS-PHIs,

as well as the needs of FS-PHIs across the country. Once additional gaps and needs of FS- PHIs are identified, the government and non-government educational organisations could design new training courses and workshops, and amend existing FS-PHI training programs to help the inspectors to accurately evaluate the safety of foods and prevent the occurrence of FBI.

If the above recommendations were introduced and implemented in the region of Hail, it is expected to have a significant improvement in public health inspection, performance management and control, and therefore improve food safety in this region.

6.2 CONCLUSION

This study investigated the food safety perception and the information needs of FS- PHIs in Hail region of KSA. With a significant proportion of respondents reporting being less than satisfied with the currently available food safety resources, the development of these resources could alleviate some of these problems. The majority of the participants referred the importance of food safety issues as very important whereas they were not confident regarding their knowledge about cross-contamination issue. FS-PHIs require regular updates to their knowledge regarding food perception, including pathogens and safety. Respondents reported the need for ongoing food safety education and training programs as well. Using KT framework might be an effective method to help FS-PHIs to improve their knowledge. This proposal would involve the translation of the results of this study into an action plan. As FS-PHIs play a vital frontline role in protecting the public from FBI, it is essential that they have the necessary knowledge and resources to perform their duties. This understanding of the perceptions, concerns and self-identified needs of public health inspectors would better enable the development of food safety information resources of direct relevance to this population.

Peachy Essay is a well reputed dissertation writing company that has all your requirements at heart. Our company genuinely offers the following services;

– Dissertation Writing Services

– Write My Dissertation

– Buy Dissertation Online

– Dissertation Editing Services

– Custom Dissertation Writing Help Service

– Dissertation Proposal Services

– Dissertation Literature Review Writing

– Dissertation Consultation Services

– Dissertation Survey Help

Our Healthcare Writing Help team provides high quality writing services in the field done by healthcare professionals:

– Healthcare Assignment Writing Services

– Healthcare Essay Writing Services

– Healthcare Dissertation Writing Services