How could the European Court of Human Rights balance the rights of religious minorities against a right to freedom of artistic expression in the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia?

Artistic expression is not a luxury, it is a necessity – a defining element of our humanity and a fundamental human right enabling everyone to develop and express their humanity.

Introduction

Art constitutes an integral part of the freedom of expression. As defined by UNESCO, ‘artistic freedom’ is the freedom to creation and distribution of diverse cultural expressions free of governmental censorship, political interference or pressures of non-state actors. It allows any person or group of people to “express their humanity, worldview and meanings assigned to their existence and development”. However, as nowadays the artistic works have an increasingly important role in spurring debates and even bringing social or political change, the governments seeking to obstruct opposition try to restrict freedom of artistic expression.

One of the most prominent international instruments, European Convention on Human Rights, provides that freedom of expression shall include right to hold opinions and receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority. However, it has to be emphasized that convention also provides for the limitations of the right to freedom of artistic expression. The governments are allowed to impose restricting measures provided that they are proportionate to the aim pursued, in accordance with the law and necessary in the democratic society.

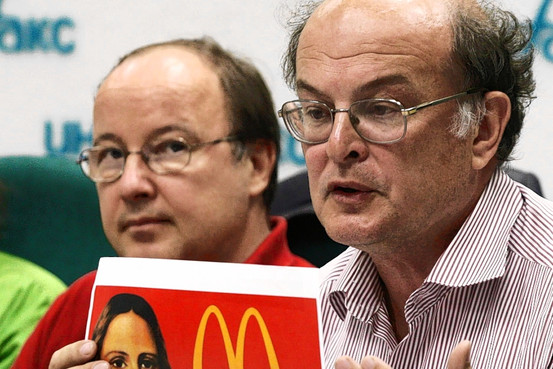

However, in reality, the measures imposed by governments do not always correspond to these requirements. One of the most remarkable examples of this is the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia which is currently pending before the ECtHR. On 12 July 2010, Moscow District Court ruled that Mr.Samodurov and Mr.Yerofeyev are criminally liable of organizing an exhibition of works that ‘incited hatred and discord and abased human dignity of Orthodox Christian’.

Their dignity was allegedly undermined because the exhibition, for example, juxtaposed holy images of Jesus Christ and Our Lady with hamburger, black caviar and soviet’s decorations. After the judgement was made, 13 Russian artists sent a letter to President Dmitry Medvedev with a petition to stop the trial, saying that the guilty verdict will amount to a sentence “for the whole of Russian contemporary art”.

However, the actions of the applicants also caused negative public opinion. For example, Oleg Kassin, representative of Council of People, group that brought the action in the first place, stated “If you like expressing yourself freely, do it at home, invite some close friend”.

Following all the controversies surrounding this case, the question to be answered in this paper is ‘How will the European Court of Human Rights balance the rights of religious minorities against a right to freedom of artistic expression in the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia?’. Due to the complexity and sensitivity of this case, it requires a careful analysis of case law concerning freedom of artistic expression and religious sensitivities.

The manner in which ECtHR reviews the case law depends on the several factors, such as background and specifics of each case. However, the outcome will also be highly influenced by political situation and cultural background of the national jurisdiction where alleged violation has taken place.

In order to answer this question, the paper will first have to establish whether the artistic works enjoy protection by freedom of expression provided for in Article 10 ECHR. As this provision does not explicitly address the artistic freedom of expression, the answer can be found in the Court’s case law. Second, this paper will present the background of the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia and give examples of the works that were exhibited. The assessment of the case will start with review of the case law on religious sensitivities and emerging trends. Although the Court has not faced a lot of precedents concerning this issue yet, it had a chance to establish some general tests, which will be applied to the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia.

Next, the paper will address the aim of the interference, which is one of the most important factors examined by the Court when freedom of expression is at stake. In this section, the discussion will focus on the juxtaposition of the aim of protection of public morals against protection of the rights of others. In the last part of the assessment, the focus will lie with the international law, which is frequently taken into account by the ECtHR.

Freedom of artistic expression under Article 10 ECHR.

Article 10 ECHR is seen as one of the most broad and controversial articles of the Convention. First of all, the broad text of this article does not provide for one freedom, but rather aims at protecting several ‘freedoms of speech’, in particular freedom to express one’s opinion, freedom to communicate information and freedom to receive information. As to freedom of artistic expression, case of Müller and Others v. Switzerland confirmed that it is also covered by Article 10 ECHR and in particularly enshrined into freedom to receive and impart ideas. It was held that the aim of protecting freedom of artistic expression is to afford the artists an opportunity “to take part in the public exchange of cultural, political and social information and ideas of all kinds”.

Court has also emphasized that states shall not “encroach unduly” on artistic freedom of expression, as artists play an essential role in the democratic society by contributing to the exchange of ideas and opinions.

Thus, although it is not explicitly deduced from the Article 10 ECHR that freedom of artistic expression is protected by the Convention, the Court has indeed confirmed that freedom of artistic expression, that also includes visual works is protected by Article 10 ECHR.

Background of the case Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia

One of the most interesting and controversial cases concerning freedom of artistic expression is Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia. This case was brought before the ECtHR because of an exhibition titled ‘Forbidden Art’ where the artists presented the works which other Moscow museums and galleries refused to display.

For example, the exhibition consisted of drawings Sermon on the Mount and Taking of Christ at the Garden of Gethsemane, in which Christ was replaced with Mickey Mouse. Another artwork that was featured at the exhibition was a collage of a fast-food restaurant’s logo and the face of Jesus Christ with a phrase ‘This is my body’. The applicants were accused on the basis of Article 282 of the Russian Criminal Code which reads as follows:

“1. Acts aimed at the incitement of hatred or discord, as well as abasement of dignity of a person or a group of persons on the ground of their sex, race, nationality, language, origin, attitude to religion, as well as affiliation to any social group, if these acts have been committed in public or with the use of mass media, shall be punishable … or by imprisonment for a term of up to two years.” District Court held that the actions of the organizers of the exhibition incited hatred to the exhibition organizers and their supporters, offended religious feelings and undermined dignity of citizens of Russia and thus they are criminally reprehensible.

Mr. Samodurov and Mr. Yerofeyev were sentenced to a fine. As application for a review of this case by ECtHR has been communicated to Russia, the main question that remains is whether the Court will decide to uphold the judgement, which was mainly made on the grounds of offending the religious sensitivities or will conclude that the freedom of expression outweighs the rights of the religious people.

Protection of religious sensibilities in the ECtHR

Although in case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia the prosecution has not explicitly addressed the religious sensibilities, their argumentation in the case very much followed the sensitivities of the Orthodox Christians. For example, the Moscow District Court stated in the final judgement that “a majority of people did not need to visit the exhibition to feel deeply offended, it was sufficient for them to find out about its existence” and that exhibition was “anti-Orthodox” and “blasphemous”.

The Court’s case law established a clear distinction between criticism of religions and gratuitously offensive expression. It has been stated that under Article 10 ECHR the expressions that are gratuitously offensive to others and can be categorized as ‘hate speech’ do not contribute to any form of public debate and hence are not protected by Article 10(1) ECHR. On the other hand, the Court has specified that ‘those who choose to exercise the freedom to manifest their religion … cannot reasonably expect to be exempt from all criticism’.

Venice Commission has emphasized that the values of the true democracy do not allow limitation of the freedom of expression simply because the view descendent from the general standards, even if these views are extreme. However, the democratic values also provide that publication of the ideas that indeed incite to hatred should be prohibited.

Thus, according to Venice Commission, it is allowed to criticise religion, even if this criticism can hurt the religious feelings, as long as this criticism does not amount to the ‘hate speech’ and hence, does not incite to hatred. Furthermore, it was noted that antagonism to the faith must be tolerated, as far as it does not attack sacred symbols or object of religious veneration.

In the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia, it is highly unlikely that the Court will be willing to accept the position of Russian Courts as the case does not concern strictly gratuitously offensive expression, but rather it involves criticism with the view of contribution to public debate. As it was stated by the European Commission on the Human Rights, the artistic works convey a view of the society on the current issues and “confront the public with the major issues of the day”. It follows that the artistic work is considered to be expression in the interests of the public discussion and a form of political speech, however harsh it can be.

It has also been argued that the current tendency is that the Court has to review its position on the protection of artistic freedom of expression and afford a greater protection as the artistic works have a considerable weight in promoting pluralism and tolerance. However, at the same time it can be taken into account that the works presented at the exhibition ‘Forbidden Art’ concerned Christian sacred symbols, which Court usually decides to protect.

In the light of the aforementioned, it can be seen that the Court has not yet faced a precedent similar to the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia where religious sensitivities would need to be balanced against a freedom of expression. In finding the balance, the Court will have to decide whether the exhibition contributed to the public debate and thus should be protected by the freedom of expression of Article 10 ECHR or was it merely a hate speech project that indeed incited hatred.

Legitimate aim pursued

One of the main factors on which the Court bases its decision is the aim of that the interference pursued. Court’s case law illustrates that even in the cases with similar background, the decision might be different if the interference pursued different aims. In the case of Muller v. Switzerland, Josef Müller and nine other applicants presented painting that illustrated fellatio, sodomy and human-animal sex in the exhibition of contemporary art.

Public prosecutor has lodged proceedings that demanded painting to be destroyed on the basis of Article 204 of the Swiss Criminal Code. This provision states that the person who displays on the public art works that are obscene, shall be imprisoned or fined. The Court confirmed that this provision pursued an aim of ‘protection of public morality’. It was concluded that the paintings “with their emphasis on sexuality in some of its crudest forms, were liable grossly to offend the sense of sexual propriety of persons of ordinary sensitivity” and hence, the measure was necessary in the democratic society.

The Court reached a similar conclusion in the case of Karttunen v Finland where the issue of protection of public morals was also at stake. The applicant in this case exhibited a work ‘the Virgin-Whore Church’, which included hundreds of photographs of teenage girls and other very young women in sexuall poses and acts. It was claimed by the applicant that the artistic work was aimed at raising awareness of child pornography.

The striking aspect of this case is that the Court has indeed considered that distribution of child pornography amounts to the exercise of freedom of expression. However, the Court decided that as the case concerned minors or persons likely to be minors, public morals and reputation and rights of others outweighed freedom of expression and thus, the complaint was found as manifestly ill-founded.

On the other hand, in the numerous decisions, the Court found that violation with the artistic freedom of expression has indeed taken place.

One of such cases, Vereinigung Bildender Künstler v. Austria, mainly dealt with the balance of personality rights against a right of artistic expression. Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Wiener Secession is an artistic association in Vienna which has held an exhibition titled ‘The century of artistic freedom’. This exhibition presented a painting of Otto Mühl, ‘Apocalypse’ which portrayed Mother Teresa, the Austrian cardinal Hermann Groer , the former head of the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) Mr Jörg Haider and Mr Meischberger, a former general secretary of the FPÖ in sexual positions. The artist illustrated Mr. Meischberger as gripping the ejaculating penis of Mr.Haider and ejaculating on Mother Teresa.

In this case, the Courts’ task was to balance rights under Article 78 of Austrian Copyright Act that provides for a prohibition of the exhibition where ‘the injury would be caused to the legitimate interests of the portrayed public’ and Article 17a of the Basic Law which provides for a freedom of artistic creation.

The national court held that although the painting indeed fell under Article 17a, the interests of Mr. Meischberger outweighed freedom of artistic expression in this case. When the case was brought before the ECtHR, the Court firstly stated that Article 10(1) ECHR is not only applicable to ideas and information that are favorably received by society, but also to the ideas and information that “offend, shock or disturb the State or any section of the population”.

The Court then proceeded by stating that the interference with the rights of association has indeed taken place, but was prescribed by law and had a legitimate aim of protection of the rights of others’. This case has a lot of value in the discussion about freedom of artistic expression because of the way that final judgement was adopted. First of all, it is worth noting that the Court did not assess the legitimate aim of ‘protection of public morality’, although it was claimed by the Austrian government.

ECtHR held that neither the wording of the legislation in issue, nor the national Austrian court referred to this aim when making a decision and thus the interference pursued a single aim of protection of Mr.Meuscgberger’s individual rights. Second, the Court eventually decided that the painting was not addressing Mr. Meischenberger private life, but rather referred to his standing as a politician. Thus, the painting merely amounted ‘to a caricature of the persons concerned using satirical element’ and the association’s rights to freedom of expression under Article 10 were violated.

However, the peculiar part of this case is that three judges issued two descending opinions where they observed that the political nature of the painting was of a minimal importance. Instead, Judge Loucaïdes wrote that ‘[n]obody can rely on the fact that he is an artist or that a work is a painting in order to escape liability for insulting others’.

The cases of Muller v Switzerland, Karttunen v Finland and Vereinigung Bildender Künstler v Austria are highly similar with one crucial difference – the aims of the interference. It can be seen that while these cases have comparable backgrounds with similar art works, the Court found a violation in Vereinigung Bildender Künstler v Austria, where the protection of rights and interests of others was at stake.

On the other hand, it did not find a violation in the cases of Muller and Karttunen, where the focus lied with the protection of public morality. Furthermore, it has to be emphasized that in the case of Karttunen, the Court combined the legitimate aim of protection of public morals with protection of rights and interests of others. This illustrates that in the instances where the protection of morals is at stake, the Court does not second-guess the domestic court’s decisions and grants a wide margin of appreciation by merely reviewing the objections against the national authorities, instead making an independent analysis of the interference.

Thus, the outcome of the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia will highly depend on the aim pursued by Russian authorities when they prosecuted the applicants. As it was established above, Court seems to allow restrictions of this kind when public morality is at stake. The provision on the basis of which Mr.Samodurov and Mr. Yerofeyev were charged addresses ‘Acts aimed at the incitement of hatred or discord, as well as abasement of dignity of a person or a group of persons…’ .

When reading this provision, it can be seen that it does not refer to the preservation of public morality, but rather addresses the rights and dignity of person or a group of persons, what in the language of the court would mean ‘rights of others’. The parallel here can be made with the case of Vereinigung Bildender Künstler v. Austria, where the Court refused to take into account the government’s argument that the interference had an aim of protecting public morality because the law that was at stake did not address it in any way.

It is highly likely that in the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia, the Court will reach a similar decision. As regards to the aim of ‘protecting rights of others’, it has to be emphasized that the case at hand does not concern a specific person, as it happened in the case of Vereinigung Bildender Künstler v. Austria, but Christian Orthodox group as a whole. In its case law, the Court has illustrated that although the State has a wide margin of appreciation, it should not be used in a way that as to accommodate minority religious beliefs.

However, even if the Court would be willing to find that there is a legitimate aim of protecting rights and interests of others, in this case, proportionality was breached as Mr. Samodurov and Mr. Yerofeyev were criminally prosecuted and fined by 100,000 rubles (approximately 2,500 euros).

International Approach to Freedom of Expression

In the last part of the assessment, this paper will focus on the international law which is frequently taken into consideration by the ECtHR. Article 19 of ICCPR provides for freedom of opinion and expression, which extends to controversial and shocking materials. Under this article, the protection should be provided for the ideas and opinions that are disliked and even incorrect.

Section 2 of this provision sets out limitations that the State might impose: (1) the interference must be in accordance with the law, (2) the restricting measure should promote or protect legitimate aim (3) the restriction shall be proportional to this legitimate aim. However, at the same time, Article 20 ICCPR provides for another restriction, namely that “Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law”.

Although from the first sight it can be seem that two articles contradict each other, UN Human Rights Committee confirmed that these provisions are not in the conflict. For example, in Ross v Canada, it was stated that “restrictions on expression which may fall within the scope of Article 20 must also be permissible under Article 19, paragraph 3, which lays down requirements for determining whether restrictions on expression are permissible.”. Thus, if the State correctly implements Article 20(2) ICCPR, this would be considered as an aim of protecting rights and interests of others, thereby fulfilling limitations set out in Article 19 ICCPR.

However, UN Special Rapporteur on the Freedom of Religion or Belief has also stated that only acts that serve as imminent violence or discrimination against a specific individual or a group will fall under the limitation of Article 20. Thus, the threshold for fulfilment of Article 20 is relatively high and “…any attempt to lower the threshold of article 20 of the Covenant would not only shrink the frontiers of free expression, but also limit freedom of religion or belief.”.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper aimed at assessing how will the ECtHR decide to balance the rights and religious sensitivities of Russian orthodox group against a freedom of expression in the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia. It was first established that Article 10 ECtHR also covers freedom of artistic expression and that the States are not allowed to restrict this rights unless the restricting measure is in accordance with the law, has a legitimate aim and is proportionate to this legitimate aim. The case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia dealt with several paintings that illustrated Christian symbols in combination with profane images. In order to answer the main question, this paper started with examination of the approach taken by the ECtHR when religious sensitivities are at stake.

The case law illustrates that the Court has drawn a clear diction between graciously offensive acts that amount to hate speech and incitement to hatred and thus should be prohibited and mere criticism that contributes to the public debate. Furthermore, nowadays the tendency has shifted to give protection to the artistic works as they provide for the expression of the public opinion on the current social and political issues. Another important factor that has to be taken into account is the legitimate aim that the interference pursues. The Court usually chooses not to second guess national court’s decisions in the instances where protection of public morals is at stake. However, in the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia, the legislation does not address the public morality but addresses the rights of religious people. In such case, the Court might choose to establish a violation if the act expresses public opinion and contributed to the debate.

In the final section of the assessment, the ICCPR was discussed. As the Court frequently decides to turn to the international instruments in order to balance the rights and interests in the correct way, the threshold set out by the ICCPR is of a high importance. Article 20 ICCPR which provides that States shall impose incitement to hatred laws will only be fulfilled if there is an ‘imminent’ violence or discrimination against individual or group of individuals.

The jurisprudence of ECtHR is dynamic and ever evolving. Nowadays, there is a tendency to give greater protection to artistic freedom of expression as it adheres to the very core of the democratic values. Thus, in the case of Samodurov and Yerofeyev v Russia, the Court might decide to change the path of existing case law around and come to an unexpected decision.

However, if the current case law of the Court is taken into account it can be concluded that freedom of expression indeed covers freedom of artistic expression. Nonetheless, if the Court finds that the works presented at the exhibition were a form of hate speech, they will not be protected by Article 10 ECHR. This paper presented the position of academics, which deem this exhibition as not being offensive, but on the contrary, contributing to the public debate. Another important factor that will influence balance of the rights in this case is the aim pursued by Russian authorities when prosecuting the applicants.

Case law illustrates that, if the Court decides to adhere to the aim of protection of public morals, there is a greater chance that the violation will not be found as the margin of appreciation given in such cases is relatively high. However, if it is held that the aim of the interference was protection of rights and interests of others, then the Court will have a chance to turn to its case law on the protection of the minorities. It is apparent that in such cases, the government has to have a neutral position and therefore the interference might not be found to be necessary in the democratic society. Furthermore, legal literature illustrates that even if it is a decision of the Court that all the preceding conditions are fulfilled, the measure imposed by Russian authorities (criminal charges and a fine) is not proportionate to the aim pursued.

We are known for our strong political science writing help team. Check out some of our services:

– Political Science Assignment Writing Services

– Political Science Essay Writing Services

– Political Science Dissertation Writing Services

Our law services are included but limited to:

– Law Essay Writing Services

– Law Dissertation Writing Services

– Law Assignment Writing Services

– Law Coursework Writing Services

– Law Report Writing Service

– BVC/BPTC Writing Service Online