Lexical Clusters (Bundles) in Written Language Corpus Analysis

By Donald Ducy

- Introduction

The lexical bundle is generated from language’s formulaic patterns and has garnered significant attention from academics over the past two decades (Biber, 2006, 2009; Biber & Barbieri, 2007; Biber & Conrad, 1999; Biber, Conrad, & Cortes, 2004; Cortes, 2002, 2004; Hyland, 2008; Wray & Perkins, 2000). The field of commonly used word sequences research builds on the work of Altenberg (1993, 1998), who developed a technique for identifying frequency-defined recurrent word combinations. Additionally, the studies classified the phrases according to grammatical and functional analyses.

Biber et al. (1999)) made the first significant contribution to corpus research by investigating these frequently occurring word combinations and proposing two categorisations, functional and structural, for the combinations in written and spoken speech. They dubbed these units’ lexical bundles’ and described them as “recurrent phrases that often co-occur in natural language usage, independent of their idiomaticity or lexical status” (p. 990). Cortes (2004) later used the term “extended collocations” to refer to lexical bundles. Numerous studies have emphasised the importance of these multi-word phrases in written communication. Lexical bundles are “critical edifices of speech” (Biber & Barbieri, 2007, p. 270). Hyland (2008) thinks that lexical bundles are critical in establishing textual coherence and making sense of a given context. For instance, phrases such as the following may be more prevalent in academic and non-academic written speech, respectively.

English language enthusiasts have traditionally used multi-word phrases such as lexical bundles in their written discourses because they are a common element of fluent linguistic output and reflect the distinctive behaviour of a mature and fluent author. Possessing the ability to utilise such structurally complicated groupings of words would instil the necessary confidence in language users to participate effectively in a writing adventure. Despite their regularity and significance, lexical bundles are not simple to grasp due to their complexity and lack of set structure (Biber & Conrad, 1999). They lack “idiomatic meaning and perceptual prominence” (Biber & Barbieri, 2007, p. 269). As a result, users of lexical bundles have traditionally struggled to activate their usage in their writing.

Meanwhile, designers and language builders have recognised that such multi-word phrases seem to be a source of confusion for language users since they lack a logical order and often co-occur in a specific text by coincidence. Certain readers of written language may even struggle to determine if a particular lexical bundle may exist in written discourse since they are unfamiliar with the forms, grammatical use, and meaning of such multi-word combinations. As a result, language authors need a concentrated emphasis on lexical bundles’ structural and functional features, and the necessity for such research is acute.

The majority of research on lexical bundles has been done on written discourse to examine various characteristics of lexical bundles in a variety of written materials from various fields or as a means of linguistic inquiry (Adel & Erman, 2012; Cortes, 2002, 2004, 2006; Hyland, 2008; Strunkyt & Jurknait, 2008). Among them, Hyland (2008) examined the form, function, and structure of the most frequently occurring four-word lexical bundles in a 3.5 million-word corpus of research articles, doctoral dissertations, and master’s theses from four disciplines: electrical engineering and microbiology in the applied and pure sciences, and business studies and applied linguistics in the social sciences. He discovered that authors from various disciplines included various discipline-specific bundles to “build their arguments, establish their authority, and convince their audience” (Hyland, 2008, p. 19). Cortes (2004) investigated the distribution of lexical bundles in the English language

Writings of university students in biology and history courses. Then, she compared their bundle use to works published in history and biology and found that only 15 bundles were utilised in history students’ papers (out of 57 target bundles in published journals). Adel and Erman (2012) performed a qualitative and quantitative research of advanced Swedish undergraduate university students’ use of lexical bundles in academic writing, comparing their findings to British native speakers to identify potential parallels and differences. They discovered that native speakers used a greater variety of lexical bundles than non-native pupils.

In contrast, researchers have treated the concept of lexical bundles or any other multi-word phrases similarly in written speech. The number of such studies seems to be increasing due to increased access to substantial online written corpora. Nesi and Basturkmen (2009) investigated the function of lexical bundles in constructing cohesion in 160 academic written discourses and discovered that lexical bundles play a significant role in cohesion formation. Khuwaileh (1999) also examined the impact of lexical bundles, phrases, and body language on Jordanian students’ comprehension of university lectures. The majority of research on lexical bundles in written discourses has been on registers other than group discussion, which is the subject of this study. The research examined academic discourse (Nesi & Basturkmen, 2009; Khuwaileh, 1999), classroom instruction (Biber, Conrad, & Cortes, 2004), and everyday writing discourses (Biber, Conrad, & Cortes, 2004). (Biber et al., 1999).

Following a study of the relevant literature, it was discovered that much research had been conducted on the written language usage of such formulaic phrases in individual and group learning. The frequency is much greater when the context of its usage in academic and non-academic discourses is considered. As a result of the need for more research on lexical bundles with emphasis on the written language, the researchers conducted a further study on the lexical bundle’s usage in academic and non-academic contexts to ascertain the extent of its use in terms of kind, structure, and function.[1]

Theory

Classical theory

According to classical theory, the structure of a notion relates to the necessary and sufficient criteria that anything must meet to fall inside this domain. Structured lexical ideas, according to this viewpoint, may be examined in terms of the smaller concepts that make them up. This idea may be traced back to the Hellenistic era when Socrates used dialogues to converse with Plato about the meanings of concepts like piety and love.[2] One frequent example is the notion [bachelor], which one might argue can be analysed in terms of a single man. According to Laurence and Margolis, one of the distinguishing characteristics of this perspective is its capacity to offer a coherent explanation for many diverse occurrences related to the idea.[3] Concept acquisition, for example, may be described as the process of integrating a concept’s definitional constituents. On the other hand, categorisation is applying ideas to just those that come under all of the concepts that make up the concept.

The theory solves the first obstacle by providing a useful composition function. Non-approximative lexical ideas may be thought of as the outcome of just conjoining the component concepts’ required and sufficient conditions. The condition is simply the structural descriptions that the constraints demand. In other words, a non-approximative lexical concept’s structure is determined by its decomposition tree, which ends at the level of basic ideas.

Second, the fact that the classical theory accounts for what Laurence and Margolis refer to as “reference determination” indicates that it also offers a reasonable Interpretation Function, satisfying requirement 2. We may conceive of the interpretation’ of [bachelor] as the junction of the extensions of [unmarried] and [male], according to this viewpoint.

The third restriction, I contend, is satisfied if – in the most specific instances (those requiring plain conjunction of ideas, as opposed to those involving idioms, metaphors, and other non-literal language norms, e.g., [stone lion], [man of steel]) – [conjunction] is also present.

Fourth, the composition function may be finitely specified in the following manner (my goal here is merely to explain the idea of giving a finite schema in which the classical theory can be shown to fulfil the stated requirement). Finally, the classical theory can be understood by recognising that objects fall under a concept (e.g., [bachelor]) by way of all of its constituents ([unmarried]) and by recognising that objects fall under a concept (e.g., [bachelor]) by way of all of its constituents ([bachelor]) and by recognising that objects fall under a concept (e.g., [bachelor]) by way of all of ([male]).

Limitations of the theory

The first criticism of the theory is Quine’s assault on the concept itself and the strange absence of uncontroversial definitions. The empirical data in the form of what is commonly referred to as “typicality effects,” which involves a variety of empirical, psychological data that has been taken to suggest that certain members of a category are more typical of that category than other members, is a second objection to the classical theory. This implies that whether or not anything comes under a notion is determined by its closeness to a prototype rather than whether or not it meets individually and collectively adequate criteria. If anything is sufficiently similar to the relevant prototype, it is considered an extension of that idea. Unlike the classical theory, which states that rigorous necessary, and sufficient criteria govern ideas, prototype theory explains concept structure in terms of characteristics that are “typical” of the things found inside their extensions.

Conceptual atomism and Fodor

All conventional theories of ideas that imply that lexical concepts are organised, according to Fodor, are similar in the sense that they are committed to the following: “primitive conceptions, and (therefore) their possession requirements, are at least partially formed by their inferential relations.” The problem with this commitment is that it implies that lexical ideas are unstructured.

This assertion implies that the existence of one idea does not presuppose or necessitate the possession of another concept.

One of its flaws is the inadequacy of conceptual atomism to account for intuitions about analytical relationships between concepts. According to Fodor, his assertion that lexical ideas are unstructured equates to the belief that possessing one concept does not necessitate or need possessing another. Despite concerns about uncontroversial definitions, it seems uncontroversial that certain ideas have a constitutive relationship. For instance, [bachelor] and [male]. When anything is referred to as a bachelor, it refers to a man. The atomist is unable to make such a link. Fodor has the strange belief that one may own [bachelor] without having [male] when it comes to idea possession.

Another criticism of conceptual atomism is its seeming adherence to extreme nativism or the belief that all basic ideas—including all lexical concepts for the atomist—are inherent. There is cause for concern since many lexical ideas seem to be excellent instances of learned notions.

The inadequacy of conceptual atomism to explain categorisation is a further concern. This difficulty may be explained because it is generally assumed that concept categorisation is explained by an object fulfilling the criteria imposed by the concept’s components, which are, of course, unavailable to the atomist. This reminds me of Fodor’s argument that, although ideas are categories, a theory of concepts does not require to explain categorisation. One answer to this debate is that, given all other factors equal, a theory of ideas that can explain classification is preferable to one that cannot.

SIMPLE TYPE THEORY

Bertrand Russell proposed Simple Type Theory to resolve set theory’s problems. The unifying features of these paradoxes (e.g., the Liar Paradox, Russell’s Paradox) are (1) self-reference: they all involve statements that include themselves in their scope (e.g., ‘this sentence is false), or sets that are members of themselves (e.g., the set of all sets); and (2) reference to all members of a particular class. Simple Type Theory was established by Russell (1908) in an effort to avoid these paradoxes. Simple Type Theory creates a hierarchy of object types that are differentiated or ordered based on the kinds of objects they accept as members. Individuals are the most fundamental, or lowest, kind of thing. Individual classes are the next lowest level of objects, and so on. Russell was able to avoid paradoxes by using a different type than classes of people because of this hierarchy of types. ‘all sets that are not members of themselves. When asked, “Is this set a member of itself?” this statement becomes problematic. It follows that if we say yes, it is a member of itself, it is not, and if we respond no, it is not a member of itself, it is. Russell’s answer was to assert that the first use of the word “set” (in the sentence “the set of all sets that are not members of themselves”) refers to a different kind of object than the second.

2.1 Previous research

Previous research on lexical bundles in writing has shown variations between L1 and L2 authors (del & Erman, 2012), beginner and experienced writers (Chen & Baker, 2010), and across fields (Cortes, 2004; Hyland, 2008). In academic writing, comparing groups showed variations in the overall frequency of usage, structural kinds of bundles utilised, and purposes provided by these bundles. Lund and Erman (2012) investigated lexical bundles in native Swedish speakers’ L2 English writing and compared them to lexical bundles identified in native English speakers’ writing at a comparable level. They found that non-native speaker has employed lexical bundles with less frequency and total type variation than native speakers in their data. There were significant functional variations in lexical bundles between the two writing samples, with native speakers using more stance (or participant-oriented) bundles and fewer discourse organisers (text-oriented bundles) than non-native speakers.

As Hyland observed in his 2008 research, lexical bundles may also differ between fields. He examined lexical bundles in papers from biology, electrical engineering, applied linguistics, and business studies. He discovered that the kinds of bundles varied between fields. Furthermore, he discovered that the distribution of available application bundles differed between fields, with applied linguistics studies, for example, using participant-oriented bundles more often than those in biology. Hyland proposed that these bundles may play a significant role in distinguishing disciplinary-specific writing and that mastery of them may help authors acquire competence in their area of study’s discourse.

Cortes (2004) discovered that history and biology students utilised few of the same bundles as experts in those disciplines. Students used less text-oriented bundles in historical writing than professionals, and they employed bundles with more significant repetition in a single text. Biology student authors shared few bundles with professional writers, which may be explained by the fact that many biology-related bundles are topic-focused and unique to high levels of research in the area. Students also used fewer quantification bundles in this case.

The previous study on lexical bundles has shown that lexical bundles are utilised differently by authors of various skill levels, linguistic origins, and fields. These differences may be seen in the general frequency of bundle use, the kinds of bundles utilised, their architecture, and their practical use. Researchers in China are increasingly interested in studying the lexical bundles seen in the academic writing of tertiary students and published authors. Wei and Lei (2011) performed a review of past studies in this field. In one study, researchers compared the 191 most commonly discovered three-word bundles in expository writing by native English speakers to those identified in timed essays produced by Chinese EFL learners. They discovered that, although approximately a third of the bundles were used in comparable proportions in the writing of native and non-native speakers, the remaining two-thirds were used with less frequency in the writing of Chinese students than in the writing of native speakers.

In contrast, they examined another research (Pang, 2009) that compared the argumentative writing of Chinese EFL learners to that of native English speakers. According to the research findings, Chinese students utilised bundles more often than native speakers, although their practical usage differed. Wei and Lei compared bundles discovered in doctorate dissertations of Chinese EFL learners to those found in professional writing in the same area in their research. They discovered that learners utilised bundles more often than professionals and that learners’ kind and purpose varied from those used by professionals. Chen and Baker (2010) also examined lexical bundles by Chinese EFL learners to native speaker writing at the undergraduate and professional levels. They discovered that not only did bundles in student writing of both non-native and native English authors vary from professional writers’ bundles in terms of frequency, kind, and function, but that beginner writers’ writing was also very comparable in these areas.

A previous study shows that, although learners employ bundles with different frequencies and functions than native-speaker authors, no one explains what they accomplish. Because the writing studied varies, it is not easy to distinguish between skill levels and text kinds.

2.2 Meaning and types of lexical bundles

Lexical bundles are defined as “the most frequent syntactic sequences in a register” (Biber et al., 2004; Biber et al., 1999; Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad, and Finegan, 1999). Lexical bundles are linguistic units, occasionally referred to as N-grams, that may or may not correspond to conventionally idealised language units and take on various shapes (NEMOTO, 2012). However, because they frequently occur in texts, they may be referred to as empirically generated units. [4]Another advantage of these bundles is that they frequently contain multiple capabilities within a single register (Johnston, 2000). The scientists discovered that classroom instruction incorporates more personal positions than academic writing (e.g., you must do so). In contrast, academic writing incorporates more impersonal positions (e.g., you are required to do so) (e.g., it is necessary). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that structural speech bundles differ between spoken and written records: if a bundle is found in the former, it is more frequently found in the latter. In his book University Language (2006), Douglas Biber asserts that “lexical bundles are necessary for discourse production in all registers” and “lexic bundles are critical for discourse growth in all university registers” (p.174). As a result, knowledge is a powerful tool for academic students interested in learning English and students in more specialised academic groups, regardless of whether they wish to study English for academic purposes (Parker, 2003).

Lexical bundles are a critical component of fluent language production because they enable effective communication (Francis et al., 1993). The question then becomes whether language enthusiasts must consciously be aware of them to learn or if they can be acquired inadvertently through observation. Crossley and Salsbury (2011) discovered that language students produced accurate two-word lexical bundles (e.g., I think, what is, and we). When the authors conducted their research, they enrolled participants in an intensive English program in the United States, and no specific lesson on bigram lexical bundles was revealed. This demonstrates that by increasing exposure to a language, the construction of bigram lexical buns and bundles may improve over time. Stengers, Boers, Housen, and Eyckmans (2010) conducted another eight-month study comparing teacher notification of chunks (a broad term that encompasses most forms of formal language) to non-notation. The findings indicated that neither the chunk knowledge in the two situations nor between them had changed. The prerequisites must be met. The outcome establishes whether students must choose more precisely defined lexical bundles explicitly in the first place.

To understand the various types of lexical backgrounds in a real case scenario, we examined four-word lexical bundles in academic publications written by Turkish academics. Biber (2006) asserts that stance bundles convey various human emotions, attitudes, points of view, certainty, and doubt. Additionally, stance bundles are classified as epistemic stance bundles or attitudinal/modality stance bundles. Bundles of epistemic attitudes are a collection of expressions that convey information about (impersonal) certainty and uncertainty (personal). When it comes to impersonal epistemic stance bundles, the TSRAC includes the following phrases: and. Despite the researcher’s awareness that universities span multiple levels, this study focuses exclusively on faculty perspectives. (Ong Sook Beng & Yuen, 2014) (Edu.)

Another bias is that a sizable portion of the available data relates to governmental involvement in the capital city’s economy, which should not be interpreted as indicative of conditions elsewhere in the empire. Attitudinal/modality stances are the second subcategory of stance bundles. They are classified into four major subcategories: desire, obligation/directive, intention/prediction, and ability. As their names imply, these lexical bundles are used to convey distinct points of view. The following TSRAC excerpts illustrate these bundles:

Our findings of single and married women emphasise the importance of gender-based divisions of labour in the home, as evidenced by married women’s delayed and weaker response to macroeconomic changes than single women. (Econ.) She was instrumental in organising the party’s women’s vote in the March 1994 municipal elections, which captured important cities such as Ankara and Istanbul and brought the party to power. (Soc.)

Finally, I hope to shed light on the discipline’s shifting boundaries by tracing how these works have been actively appropriated and filtered through the conceptual grid of current debates and ongoing events in the public sphere. Organisers of discourse (in the social sciences): The lexical bundles in this category introduce or elaborate/clarify a subject. As demonstrated in the examples below, the majority of the discovered lexical bundles were used for elaboration and explanation:

In comparison, adjustments to inflation made after January 1, 2004, will affect the tax calculation (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2004b). (Econ.) As a result, researchers used rigorous and exhaustive methods to investigate the effects of cultural orientation differences in addition to demographic and organisational variables. (Soc.): Other-than-self-referential expressions Referential expressions are the final broad category, as they are critical in determining the functions of lexical bundles. “In general, the bundles in this category emphasise the importance of an entity or a specific property of an entity,” Biber et al. write (2004). (p.393). It consists of four sections: identification and focus, imprecision, typical specification, time, place, and text reference. As Cortes (2008) did with her categorisation, it was decided to broaden the referential category by including a sub-group dubbed institutions. The Ministry of Education*, the Ministry of*, the Turkish Republic*, the Ministry of National Education*, by the Ministry of*, at the University of*, and the Ministry of National Education* are among the lexical bundles that refer to institutions.

Surprisingly, every type of referential bundle was identified in the TSRAC during the overall study of lexical bundles, except for imprecision. Further investigation of the discovered lexical bundles necessitated adding a new category to the taxonomy under consideration, dubbed “research referential.” The TSRA corpus contains a large number of novel lexical bundles. He defined research in his study as “assisting authors in structuring their actions and experiences in the real world” (Hyland, 2008). (p. He included bundles such as the study’s origin, purpose, and scope in this group. When compared to the TSRAC’s research-oriented bundles, Hylands’ classification was found to be excessively broad, and none of the bundles discovered in the TSRAC, except those created specifically for this study, had been identified and included in Hylands’ group of research-oriented bundles. Unlike Hyland’s bundles, the TSRAC’s research referential bundles, as illustrated in Table 4.1, are unique to each study and contain information about the study’s objective, method, findings, and participants.

In contrast to text deixis, research referential lexical bundles refer to the study itself (article or report) instead of the inquiry or investigation. When the lexical bundles of the referential research group were examined, it was discovered that they refer to the study’s overarching characteristics rather than the text itself. As demonstrated by the examples, participation in the study is synonymous with participation in the research. As illustrated in the examples below, these referential research bundles do not refer to the text but rather to the study, the activities necessary to conduct the study, or the individuals who participated. In May 2005, 223 teacher educators and 2,116 prospective teachers were selected from these schools and asked to complete a questionnaire as part of the research. Two hundred twenty-three teacher educators and 2,116 prospective teachers responded to the survey. In June and July 2005, the second round of surveys was sent to individuals who had not responded to the first round of questions. (Edu.) The poll included supervisors from eight different cities. (Edu.) Four weeks after completing the instrument the first time, respondents completed it again. (Med.) According to the researchers, the purpose of this study was to ascertain the current use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in Turkish hospitals and the variables associated with effective surgical antibiotic prophylaxis. Even though some patients were unable to be assessed during the third stage, all patients admitted to the research clinic for evaluation by the study physician were diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder or dissociation disorder NOS. (Psyc.) Except for the lexical bundle, none of the fifteen research-referential lexical bundles had been identified in the literature before this study’s findings were published.

To summarise, Turkish authors frequently employed lexical bundles. While some of these lexical bundles had previously been identified in the literature, over half were not recognised as frequently occurring lexical bundles. Even though Turkish scholars employed lexical bundles that native English speakers do not frequently employ in their written work, they were successful because all of the articles included in the TSRAC had previously been published in reputable journals within the disciplines studied. This may indicate a stylistic difference between native and non-native English speakers who use lexical bundles in academic writing. According to the findings, there is a difference in how lexical bundles are used in academic contexts between this subgroup of non-native English speakers and native English speakers.

2.3 Classification of lexical bundle

There are two ways to categorise lexical bundles. The first is based on their structural patterns and their function in the discourse environment.[5] The first structural categorisation was suggested by Biber et al.. The most common lexical bundles were divided into fourteen structural categories in conversation and twelve structural categories in academic writing, based on their frequency of occurrence. When it comes to the structural study of lexical bundles, their approach has been cited as a significant source of inspiration.[6] Though lexical bundles are identified purely based on frequency, without considering structural or functional characteristics, Biber and colleagues believe that these semantic clusters are “decipherable across both functional and structural terms” (p. 399).

Biber et al. (Parker, 2003) [7]Developed the first structural classification, in which the most frequently occurring lexical bundles were classified into 14 structural categories in conversations and 12 structural categories in academic writing, based on the frequency with which they were encountered in the texts. A significant source of inspiration for structural analyses of lexical bundles was cited due to their approach.

Regarding functionality, two taxonomies are frequently used in conjunction with one another. As a result of the Research, Biber, et al.[1] identified three main functions: (1) expression of the viewpoint of ‘attitudes or assessments of certainty,’ (2) speech organisers for “reflecting relations between preceding and future speeches,” 3) bundles of references that make direct reference to biological abstracts or emphasise a specific attribute of a particular entity (ibid., p. 384). Following the work of Biber and his colleagues [1,] Hyland presented its lexical bundle functional taxonomy, which is comprised of (1) research-oriented bundles that “assist authors in organising their activities and real-world experiences,” and (2) lexical bundles that “assist authors in organising their activities and real-world experiences.” (2) bundles that are ‘preoccupied with the organisation of a text and its significance as a message or argument,’ and (3) bundles that are ‘centered on writers’ involvement in a research endeavour,’ are also included in this category (ibid., p. 13).

2.4 Collocations – meaning and difference between lexical bundles

“Collocations (…) are relationships between lexical terms in which the words appear more often than would be anticipated by chance” (Biber et al. 1999: 998). They were discovered using two different approaches: the phraseological method demands that a collocation satisfy particular meaning or restrictiveness requirements. In contrast, the statistical approach quantifies the frequency of co-occurrence and mutual expectation quantitatively quantified (Barfield 2012). This method results in a variety of objects being categorised and tallied as collocations. Collocations were defined in this research using a corpus-based statistical method, without any extra semantics. L. Vilkait Contrast the frequency of idiomatic phrases, collocations, lexical bundles, and phrasal verbs with formulaic language. Taikomoji kalbotyra 2016 (8), www.taikomojikalbotyra.Lt adopts the following criteria. Consider the following collocations: take care, yesterday night, and learning problems.

Collocations are a common, and therefore a significant feature of the English language. McCarthy further said that “collocation ought to be a primary focus of vocabulary instruction” (1990: 12). Shin and Nation (2008) demonstrated that some collocations are often used enough to be included in lists of the most frequently occurring 2000 words. Although collocations are deemed ordinary, no study has been conducted to determine how the proportion of collocations changes between registers.

Collocation is a term used and understood in a wide range of situations. Lexical bundles are a subset of extended collocations that occur more frequently than expected; they are regarded as discourse building blocks and play a critical role in textual consistency. They aid in comprehending the meaning of specific contexts of language use and establishing a sense of flow and rhythm throughout the discourse. However, it is impossible to present and discuss all possible interpretations of the term within the limits of this article. Instead, this article will summarise Benson, Benson, and Ilson’s definition and use of this term (1986a-b):

Like other languages, English has a considerable number of fixed, recognisable, non-language phrases and structures. These word clusters are referred to as “recurring combinations.” The term “fixed combinations” or “collocations.” Two types of grammatical collocations are classified: grammatical collocations and lexical collocations. Grammatical collocations consist of a noun, an adjective or a verb, a particle (a preposition, an adverb, or a grammatical structure such as an infinitive or gerund or clause)(Bahns, 1993:57).

“Lexical bundles are extended collocations: groupings of words with a statistical propensity for co-occurrence” (Biber et al. 1999: pg.989). Because their extraction is simply based on frequency, there are no further criteria for well-formedness or meaning independence, and I think they would both be classed as lexical bundles. However, a study of the sequences shows that The data gathered revealed that lexical bundles often serve functional purposes such as communicating attitude, organising speech, and expressing referential meaning (Biber et al. 2004). As a consequence, they seem to be more than random word co-occurrences. There are two significant differences. Distinguishing between lexical bundles and collocations: First, lexical bundles are longer (three or more words) and more well-defined sequences. Second, they are distinguished only by their frequency of occurrence, with no need that the words in the bundle be mutually expectant. Lexical bundles were discovered to account for about 30% of conversation and 21% of academic discourse. Biber et al. (1999). Because of the prevalence of these sequences, studies concentrating only on idiomatic formulaic language have been conducted (Conrad & Biber 2004). Consequently, the present study included lexical bundles retrieved using corpus-based criteria (Biber et al. 2004, 1999; Conrad & Biber 2004)

- Research

Preview of the Research

My research aims to address a knowledge gap regarding the form and function of lexical bundles found in undergraduate theses and how they relate to lexical bundles utilised by professional authors. We examine lexical bundles’ prevalence, forms, and roles in academic study writing and expert writing and across applied linguistics and literature fields. The current study seeks to provide an answer to the following research question:

What are the variations in (a) frequency, (b) structural kinds, and (c) functions between the lexical bundles employed by students and professional authors in applied linguistics and English literature?

Methodology

The frequency, structure, and function of lexical bundles discovered in literary and applied linguistics work created by published authors and theses from students at higher learning institutions were compared in this research. The methodology of the current research is described in this section. The first part will include information about the University where the undergraduate writing was completed. In this part, I will explain the thesis writing requirements for foreign language students and the basic features of Longdong University. The second part describes the study’s corpora design and corpus compilation methods.

The context of the research

Undergraduate theses from students at the School of Foreign Service were included in this research. Languages and Literature at Longdong Institution, a four-year university in Gansu province in north-central China’s Gansu province. This department had 3000 students overall as of the 2019-2020 academic year, with 20 “classes” of students throughout all four years. In Chinese schools, these “classes” are organisational units, with each class consisting of about 25-30 pupils. Each class studies introductory courses, live in dorms and engages in weekly class activities together.

Each grade level at Longdong University includes five courses, four of which prepare to become primary or middle school teachers. One is preparing for a profession in translation or interpretation (Waiguoyu Xueyuan Jianjie, 1/9/2021). Throughout the four years, the basic subjects include English language and literature. In their fourth year, all students are expected to submit a thesis. The vast majority of these theses are authored in English.

Those published in Chinese often examine certain aspects of either Russian or Japanese, which are foreign languages that students must study for two years. Most students are at an intermediate competence level in English by their senior year, having studied English for 8-12 years before university entrance and then four years of college academic work in English. Students complete three semesters of writing courses, including a practical business writing course their freshman year and a two-semester writing course their sophomore year and the first semester of their junior year. Foreign instructors are most frequently used to teach practical business writing and general writing courses. The topic of these courses varies according to the instructor, and they may or may not serve as preparation for writing a thesis.

Senior thesis requirements

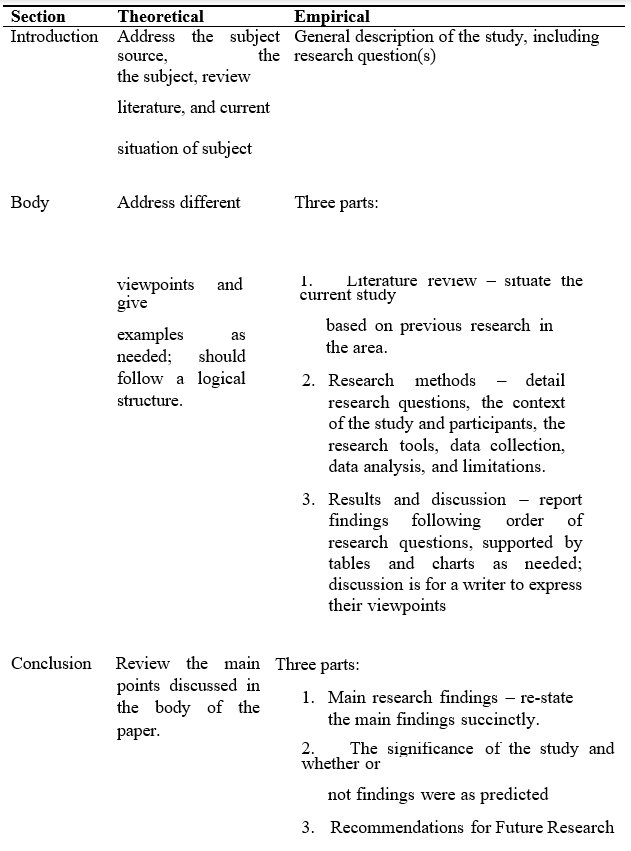

During their final year, students are handed written instructions outlining the University’s thesis requirements. Professors have produced these in the College of Foreign Languages and Literature in compliance with the Ministry of Education’s standards, which require all four-year university students to submit a thesis in their final year. There is no course at this institution that is related to this text. The paper is in Chinese and outlines the thesis’s necessary parts. It requires a cover page, a declaration of academic integrity, an abstract containing at least three keywords, and the main content of the paper. Except for the primary text, all components should be available in both English and Chinese. The paper describes two kinds of theses: theoretical and empirical. Theses in literature are theoretical, while applied linguistics adhere to empirical research writing standards. While both kinds need an introduction, body, and conclusion, the content of each part changes depending on the type. Table 1 provides an overview of these criteria. The paper also specifies basic formatting criteria, such as how to number chapters, which font and font size to use, and how to include page numbers. It is essential to note that, although the document specifies what should be included in each part, it does not specify how the material should be presented.

Table 1. Guidelines for senior thesis writing.

Besides the thesis requirements paper, students get two thesis outlines that demonstrate the basic criteria for formatting. A paper explaining APA citation styles, delivered in English, is also provided.

In preparation for the thesis, students choose from a range of around 200 subjects, including applied linguistics, literary analysis, cultural studies, or philosophy of translation. Some themes, for example, are as follows: Genre-oriented approach to high-school teaching in China, the cultural impact of university English teaching in China, the life-philosophy in the older man and the sea.

The final criteria are a thesis of at least 5000 words, including all the theoretical or empirical research parts, and is consistent with the APA quotation style and the University standards for formatting. Students finish their theses during the last weeks of the winter semester and the beginning of the spring semester. During this phase, they engage with a consultant to complete and modify draught documents. Students must present and modify at least three thesis draughts. In all, students have approximately four months from subject selection to thesis defence.

Procedures for compiling and designing corpora

In order to conduct this study, two corpora were gathered. Longdong University produced a learner corpus consisting of applied linguistics and literary texts between 2019 and 2020, used in one of the studies. The second was a comparative corpus of professional writing composed of applied linguistics and literature papers published in refereed journals between 2019 and 2020. It was composed of papers that were published in refereed journals between 2019 and 2020. The processes for designing and compiling both corpora are described in detail in the following sections.

Learner corpus

This term commonly refers to a group of people who have learned something new. Any student thesis written in English and published at Longdong University was eligible for consideration between the 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 academic years. These theses were published and made available to the public at the university library; no electronic versions were available at the time. A list of theses published between those years was compiled in the following order: class order, followed by the year of publication, so the list began with Class 1 writings from the 2018-2019 academic year and progressed sequentially through Class 5 theses from the 2019-2020 academic year, and so on.

In 2020, there will be a leap year. This collection did not include any student theses written in Chinese. Student theses covered topics such as applied linguistics, literature, translation theory, and cultural studies. Two research fields were chosen to achieve the study’s objectives: applied linguistics and literature to compare and contrast. There were 108 theses in applied linguistics and 55 theses in literature submitted in total.

This was the list from which I chose every third thesis in each subject area. As a result of this process, 34 applied linguistics texts and 17 literary texts were added to the learner corpus. While the small number of texts, particularly in literature, limits the generalizability of the results, they may still provide valuable preliminary information about the lexical bundle use of these Chinese students.

I retyped the abstracts and main text of these theses for this study, excluding the title page, acknowledgements, tables and charts, and reference sections because they were unrelated to the current investigation. Since the theses were obtained from the library, no information about the students’ performance was available.

Corpus of Professionals

The comparisons were compiled from publications in standard academic papers on applied linguistic Research and literary analysis. Professional articles are not an exact match for the student writing corpus, but I chose to use them instead of student theses in a country where English is widely spoken because they most closely reflect the final goal of Longdong students. According to a recent study on the frequency and structural types of bundles, authors from L1 and L2 universities differed from experienced writers when using bundles (Chen and Baker, 2010). Because this study found that L1 authors continue to use bundles differently than experts with comparable levels of disciplinary competence to L2, comparing existing learner writing examples with those of similar authors would only provide an overview of the differences. This study aims not only to describe differences between learners but also to provide recommendations and ideas in areas that may eventually improve learner writing. To that end, following Cortes’ (2004) research of lexical bundles in native-speaking students and professional writing, I chose experts in writing for comparison, as this would indicate that disparities between the students and their goals could be addressed.

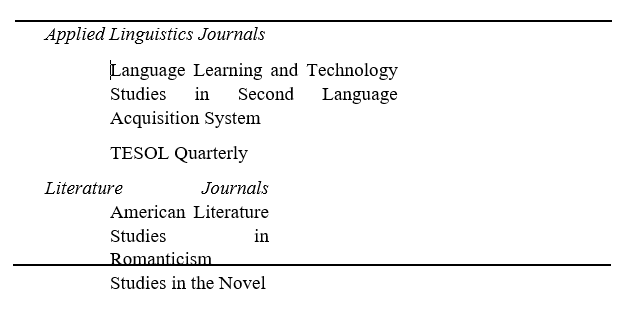

Table 2 lists the journals that were used. The journals were chosen as notable in their fields of study by the Portland State University library’s website. I chose journals from various publishers to include journals of various styles. I also wanted to provide journals focusing on a variety of subject areas to avoid duplicating content-specific bundles. Because the corpus of literature students is smaller than applied linguistics, one fewer literature magazine has been chosen.

Table 2 Journals used for the professional corpora

Applied Linguistics Journals

Language Learning and Technology Studies in Second Language Acquisition System

TESOL Quarterly

Literature Journals American Literature Studies in Romanticism Studies in the Novel

As I did with the learner corpus, I created a list of all articles from those journals, in the same way I did with the learner corpus: texts from the first volume published in 2018 were ordered chronologically, and the list ended with texts from the last volume published in 2020. Despite the small size of the learner corpora, I need a bigger professional corpus for comparison since professional publications are more likely to include a wider range of subjects and subtopics. For example, students are limited to a narrow number of courses, while professional subjects may be very varied. Unlike the kids, whom all have a similar upbringing, the article authors come from a more varied range of situations. As a result, a bigger corpus is needed to capture professional writing variation and discover lexical bundles.

As a consequence, I chose roughly twice as many texts from professional writing as from learner writing. As a consequence of this arrangement, every fourth journal article was selected from the gathered lists. This initiative selected 58 papers from practical linguistics publications and 31 articles from literary journals for 58 articles.

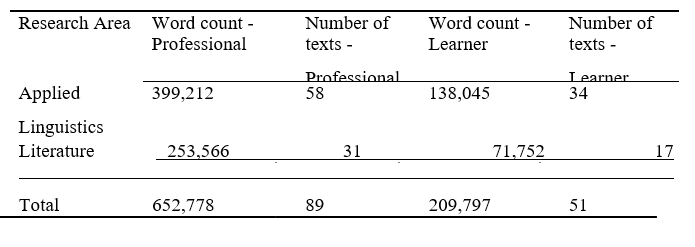

Table 3 summarises the size of each corpus. Professional corpora are considerably bigger than student corpora, which makes sense given the increased availability of literature. Previously, comparable studies comparing corpora of different sizes to mine have been performed (e.g., Adel and Erman, 2012; Cortes, 2013; Hyland, 2008). As a result, the frequencies shown in the data are not raw but have been normalised to their occurrence per 100,000 words to account for the size disparity.

Table 3. Corpora used in the present study

Data analysis

The analysis of the study is divided into three sections. The first addresses frequency, the second structural type, and the third functionality. However, before I could begin analysing, I had to determine how long I wanted the bundles to be. In the past, three- to five-word bundles were used (Cortes, 2004). However, most lexical bundle research focuses on four-word bundles because they occur more frequently than five-word bundles, and many three-word bundles are parts of larger, four-word bundles (Chen and Baker, 2010; Cortes, 2004). As a result, I decided to focus on four-word bundles and five-word bundles that indicated an overlap in two four-word bundles (for example, at the start of and at the start of the).

Frequency analysis

When detecting lexical bundles, two elements of frequency are critical: the frequency with which the bundles appear and the range of texts in which the bundles occur. The frequency of occurrence threshold varies according to the kind of corpus investigated. As stated in the literature study, written language has fewer lexical bundles than spoken language. While the lowest frequency threshold for spoken data is typically set at 40 times per million words (e.g. Biber et al. 1999), this threshold can be set lower for written data by looking for bundles that occur at least ten times per million words. However, some studies set the frequency higher at 20 times per million words (Cortes, 2004).

Additionally, bundles must occur throughout a variety of texts. This range is essential because if a lexical bundle appears in many texts, it is more likely to represent a formulaic sequence than an authorial idiosyncrasy (Biber, 2009). The range is determined by the research but is often between three and five texts (Chen and Baker, 2010).

Due to the limited size of certain corpora, I decided to examine bundles that appeared at least 20 times per million words across four books. This is consistent with prior studies comparing learner and professional writing (e.g., Chen and Baker, 2010; Hyland, 2008), but data on the frequency and range cut-offs are not entirely consistent.

After configuring these settings, I extracted possible bundles using AntConc version 3.4.3, a free concordancer created by Lawrence Anthony (2014). I next examined the data for overlaps and adjusted the raw data set manually. For instance, at the start of and the start of both happened with equal frequency and When verified, range and were both parts of a bigger five-word bundle at the start of the. In some instances, four-word bundles were included as part of a bigger five-word bundle and fulfilled the requirements for inclusion as a four-word bundle. For instance, in addition to existing as a four-word bundle, pay more attention to what was included in the five-word bundles should pay more attention to and pay more attention to. In these instances, the five-word bundles were retrieved, and the counts of the original four-word bundles were modified to guarantee that each bundle appeared only once in the data.

Thus, my final list of lexical bundles included all four- and five-word lexical bundles that appeared at least 20 times per million words in at least four texts from one of the corpora. My study topic was addressed in part one by comparing the frequency of lexical bundles among fields and writer groups.

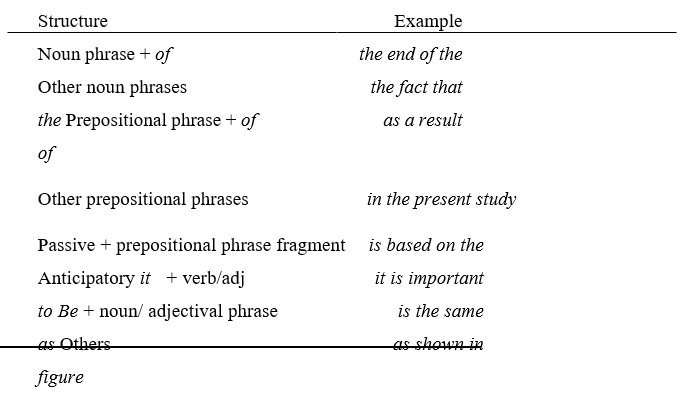

I then categorised bundles based on their structural characteristics. I adhered to the criteria established by Biber et al. (1999) and revised by Hyland (2008). Table 4 summarises the eight categories. My second study question was addressed by comparing the prevalence and usage of structural types among expert authors in both areas and between learners and experts within each subject.

Table 4. Structural categorisation of lexical bundles

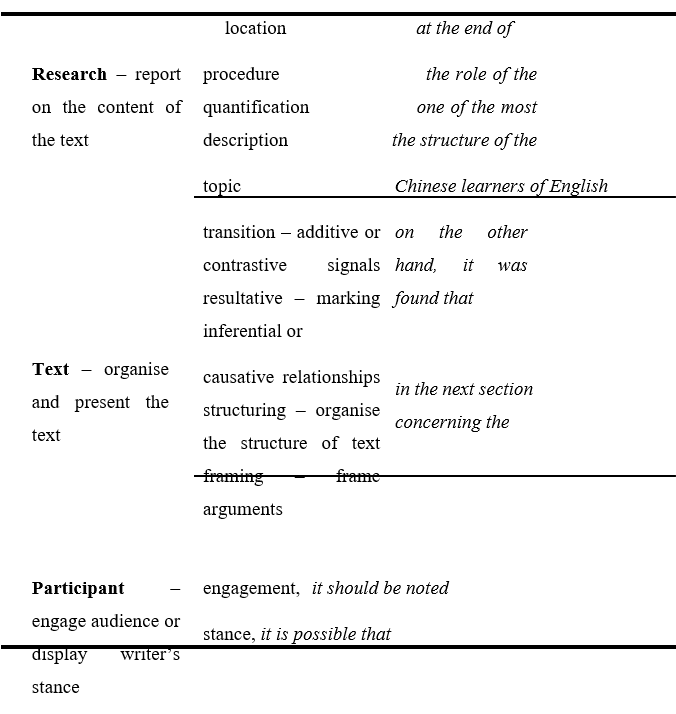

I then performed a function analysis on the bundles. The functional classification was done per the methodology established and applied in an earlier study (Hyland, 2008, pp. 13-14). It is divided into three main functional groups, which are explained and illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5. Functional categories of bundles

Text – organise and present the text transition – additive or contrastive signals resultative – marking inferential or causative relationships structuring – organise the structure of text framing – frame arguments on the other hand, it was found that in the next section concerning the

Participant – engage audience or display writer’s stance engagement, it should be noted stance, it is possible that

I looked at occurrences of each bundle in context to categorise its function within the text. Some bundles were more difficult to categorise, as categorisation systems were not clear on the distinction between description and topic. I made my best efforts to categorise the bundles according to descriptions given in previous research. For bundles that seemed to have multiple functions, such as at the same time, I categorised them according to which function seemed most dominant based on their use in context. So while Hyland (2008) categorised at the same time as locational bundles, I found that most of the ones present in my corpus were transition bundles, so I analysed the data as if they were all transition bundles. I did this instead of analysing them according to the proportional use of each function due to the quantity of data and time limitations. I will discuss the limitations of using this categorisation method further in Chapter 5. The third part of the research question was answered by comparing the functions of the bundles within the two subjects and between experts in each subject area

Results and Discussion

This section summarises and discusses the study’s results. To begin, I examine the overall frequency of bundles discovered in learner and professional corpora. I then describe the structural kinds of bundles discovered inside each corpus and compare them to those discovered across and within topic areas. Finally, I show and analyse the functional category bundles and compare their functional applications across topic areas and between professional and learner writing within the same subject area.

The overall frequency of lexical bundles

This section addresses the first component of the study issue, which is the variation in the frequency of bundles across competence levels and topic areas. All statistics given for the frequency of lexical bundles are normalised to their frequency per 100,000 words. The Appendix contains a full list of all bundles from the professional and learner corpora.

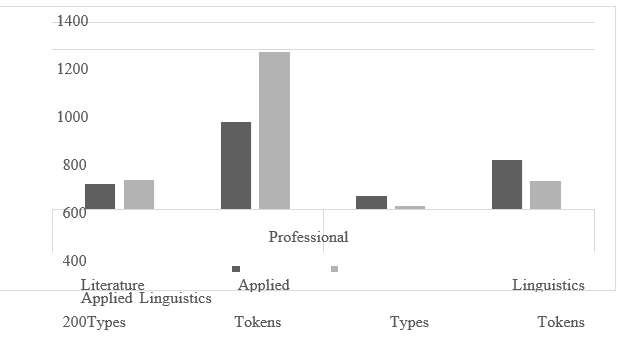

The total count of bundles utilised within each group is summarised in Figure 1. It demonstrates that both professional and student writing in applied linguistics includes more bundle types and tokens of those bundles than literary writing. However, students writing in applied linguistics utilised more bundles and did so more often than experts. The results were the reverse for literary writing, with trainees using fewer kinds of bundles and at a lower frequency than expert writers. The increased usage of bundles in applied linguistics writing may be related to how applied linguistics writing is organised, with the more formulaic language used in the methods and results in parts of publications. Additionally, the applied linguistics literature emphasised instructional themes and second language acquisition, and the language used to express these areas may be more formulaic.

Figure 1: Counts of bundle clusters and tokens within groupings (per 100,000 words)

Frequency of Bundles between professional grouping

Within professional writing, literature makes use of fewer total tokens and bundle kinds than linguistics does. Table 6 shows the twenty most often used bundles across all categories, with the two professional groups sharing six bundles. This demonstrates that bundles are employed throughout a comparable range of texts in both topic areas; they are often utilised in linguistics writing. One exception was concurrent, which was more often used in literature. This bundle’s very frequent usage seemed to be linked to explaining what literature accomplishes and how it impacts readers. In this manner, amazement captivates us while transporting our senses to new heights of pleasure. (Literature, 2013, vol. 4, p. 4).

Wallace creates posthumanist fiction that upholds and supports humanism while acknowledging and grappling with the twenty-first century’s adverse social and cultural milieux. (2012, literature, p. 26). This form was also employed in linguistics, but mainly to report on concurrent activities occurring throughout the study.

A comparable small proportion of students strongly agreed that listening to auditory information and reading test questions concurrently was difficult, with the rest remaining neutral—language and Linguistics, 2013, p. 32. In general, the most significant distinction between groups of professional authors is the frequency with which bundles are utilised. While professionals shared a limited number of bundles, linguists used them more often and across a broader variety of texts than literary authors.

Between the two groups, learners shared five bundles (Table 6), but what is noteworthy about their twenty most common bundles is that many of the bundles are topic-specific (e.g. in junior middle school; falls in love with; students interested in learning). The bundles indicate what they were writing about, while the professional bundles do not.

Table 6. Twenty most frequent bundles in professional writing across both subjects

| Professionals – Range

Linguistics Freq (58) |

Professionals – Range

Literature Freq (34) |

|||||||||

| as well as the | 58 | 15 | at the same time | 38 | 15 | |||||

| on the other hand | 50 | 13 | in the united states | 33 | 13 | |||||

| the extent to which | 49 | 12 | as well as the | 20 | 8 | |||||

| the results of the | 46 | 12 | in the face of | 20 | 8 | |||||

| in the context of | 45 | 11 | in the first place | 19 | 7 | |||||

| in the present study | 42 | 11 | on the one hand | 19 | 7 | |||||

| in the united states | 40 | 10 | in the midst of | 18 | 7 | |||||

| in the current study | 37 | 9 | the figure of the | 18 | 7 | |||||

| at the same time | 36 | 9 | in the context of | 17 | 7 | |||||

| there was a significant | 31 | 8 | at the end of the | 16 | 6 | |||||

| in the target language | 30 | 8 | the end of the | 16 | 6 | |||||

| of the present study | 30 | 8 | in the words of | 14 | 6 | |||||

| the fact that the | 27 | 7 | as a form of | 13 | 5 | |||||

| as a result of | 26 | 7 | in the form of | 13 | 5 | |||||

| it is important to | 26 | 7 | the story of the | 13 | 5 | |||||

| in terms of the | 24 | 6 | as a kind of | 12 | 5 | |||||

| at the end of the | 23 | 6 | in a way that | 12 | 5 | |||||

| At the beginning of the | 22 | 6 | in the case of | 12 | 5 | |||||

| the use of the | 22 | 6 | in this way the | 12 | 5 | |||||

| in the field of 21 5 on the other hand 12 5 | ||||||||||

| Learners – | Range | Range | ||||||||

| Linguistics Freq (34) Learners – Literature Freq (17) | ||||||||||

| task-based language | ||||||||||

| Teaching | 66 | 4 | at the same time | 24 | 13 | |||||

| in the process of | 37 | 15 | falls in love with | 10 | 6 | |||||

| at the same time | 24 | 13 | in the novel the | 10 | 5 | |||||

| as well as the | 23 | 12 | at the same time she | 10 | 4 | |||||

| that is to say | 20 | 13 | we can see that | 10 | 5 | |||||

| in junior middle school | 19 | 6 | is one of the | 8 | 5 | |||||

| is one of the | 16 | 10 | all over the world | 8 | 4 | |||||

| plays an important | ||||||||||

| on the other hand | 16 | 12 | role in | 8 | 5 | |||||

| is a kind of | 15 | 10 | on the other hand | 8 | 4 | |||||

| to communicate in | ||||||||||

| English | 15 | 4 | one of the most | 8 | 4 | |||||

| between teachers and

students |

14 |

7 |

in the 19th century |

7 |

5 |

|||||

| of the target language | 14 | 9 | as well as the | 7 | 4 | |||||

| students interest in | 14 | 5 | for the first time | 7 | 4 | |||||

Frequency of Bundles between learners.

Role-playing is a critical component of middle school English instruction. The majority of pupils are uninterested in studying English; the majority believe English to be a required subject on the school curriculum. Students utilised a broader variety of bundles and did so more often than professionals. The learner corpus’s most commonly utilised bundle, task-based language learning, happened 66 times per 100,000 words. However, this bundle was found in just four books.

There are many things to consider while adopting task-based language instruction. This bundle does not often appear in the professional corpus, but it was mentioned in seven papers. Additionally, the most common bundle happened 15 times every 100,000 words. In other words, this bundle is used by fewer students, but they utilise it more.

Overall, structural usage varied across experts in both areas and within each field. The + N + of and in the + N +of exhibited significant variance across disciplines and within disciplines. The nouns selected to fill the N slot varied greatly across the two disciplines, where there was only one common bundle between the two groups. Both fields had a limited range of nouns to choose from, but applied linguistics had a larger diversity. Learning and practical usage of applied linguistics may differ according to the varying data types reported. The words chosen to fill the gap in literature were more varied than those used in practical linguistics. Professionals in both literature and applied linguistics utilised more words than students. The process was the sole noun used in this construction in both topics.

Learner corpus Other noun phrases had learners utilising the present tense of the verb, whereas the professional corpus had comparable bundles using the past tense.

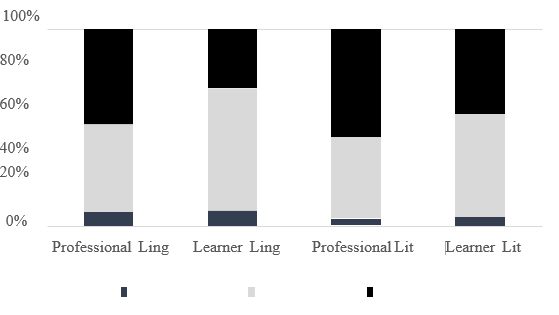

4.3 Bundle functionality

This section reports the findings of the functional distribution of bundles based on Chapter 3’s classification. Figure 2 shows the distribution of functional bundles among the four corpora. These bundles are less prevalent in literary writing than in applied linguistics writing at both levels of competence. Professional writing in both domains uses this functional type more often than learner writing in both areas. Professionals have more research-oriented bundles than learners in certain domains.

Figure 2. Functional use of bundles in each corpus as a percentage of total tokens

Professional authors wrote them in applied linguistics and literature. Participant-oriented bundles were utilised the least in both groups, accounting for fewer than 10% of all bundles. The rest were divided. a mix of research and text

Literature professionals utilised text-oriented bundles the most, accounting for almost half of all bundles used. Professionals in applied linguistics utilised research- and text-oriented bundles equally, accounting for about 45 per cent of total functional bundles.

In terms of participant-oriented bundling, students act like professional authors. However, applied linguistics students employ more research-oriented bundles and less text-oriented bundles than professionals.

CONCLUSION

Despite the need for further research, the findings of this study provide the first glimpse into the writing practises of intermediate language learners at this institution and how they compare to professional writing in related areas. The research contributes significantly to our understanding of second language writing and student requirements. Chinese English learners have received little attention, and analysing their writing may help us understand what they are capable of with their current level of teaching. Additionally, although the main objective of this research was to explain the distinctions between professional and learner writing, the findings have implications for Longdong University’s writing programme. Finally, although this study cannot offer an exhaustive account of lexical bundles in various fields, I hope that future research will include the recommendations made above to further our knowledge of lexical bundle disciplinary diversity.

Lexical clusters (bundles) in written language corpus analysis. Multi-word phrases often co-occur in natural language usage, independent of their idiomaticity or lexical status. Lexical bundles are critical in establishing textual coherence and making sense of a given context. The majority of research on lexical bundles in written discourse has focused on group discussion. A study by Hyland examined the form, function, and structure of four-word lexical bundles in a 3.5 million-word corpus of research articles.

Laurence and Margolis studied lexical bundles’ usage in academic and non-academic contexts. They found that a lexical bundle’s structure can be examined in terms of its structure, kind, structure, and function. The researchers say this could lead to more research into lexical concepts. Conceptual atomism states that rigorous necessary, and sufficient criteria govern the structure of ideas. Quine argues that it implies that lexical ideas are unstructured.

Theory’s flaws include Quine’s assault on the concept itself, as well as the strange absence of definitions. Conceptual atomism has been criticised for its belief that all lexical concepts are inherent. Bertrand Russell proposed Simple Type Theory to resolve set theory’s problems. Theory of ideas that can explain classification is preferable to one that cannot, says Fodor. Non-native speakers used lexical bundles with less frequency and total type variation than native speaker authors.

Researchers found significant functional variations in the usage of lexical bundles between the two writing samples, with native speakers using more stance (or participant-oriented) bundles. Chen and Baker (2010) examined lexical bundles by Chinese EFL learners to native speaker writing at the undergraduate and professional levels. They discovered that learners utilised bundles more often than professionals. The purpose of bundles used by learners varied from those used by professionals. Stengers, Boers, Housen, and Eyckmans (2010) conducted an eight-month study comparing teacher notification of chunks (a broad term that encompasses most forms of formal language) to non-notation.

Findings indicated that neither the chunk knowledge in the two situations nor the chunk between them had changed. Inflation adjustments made after January 1, 2004, will affect the tax calculation. Researchers used rigorous and exhaustive methods to investigate the effects of cultural orientation differences in addition to demographic and organisational variables.[8]

When the notion of lexical clusters comes to mind, it is evident that they relate to a general collection of words that interrelate to each other and possess similar linkage structure in a way that is similar to other words, statistically. As such, words that relate to each other, such as; beans, cowpeas, and French beans, portray a property from which they are put to use in similar phrases. This cluster of words can be grouped because they have a similar global concept to imply legumes. It is essential to understand what the corpus analysis in written language pertains to. For instance, when reading the news, a person will probably skim through or read the posts and other columns from the start and progresses deep into the material. In the classroom context, the learner and the instructor could think of factors in writing down individual texts, such as the purpose of a project or genre.

The learner and the tutor are heedful to the factors of rhetorical contexts in numerous texts. However, in stark contrast, it is most likely that one spends less time surmising how the language has been used through the text they read or write, especially in words, sentences, and phrases. It is crucial to understand that one may think about patterns of language, even without realizing it. This is because it is a section of why an individual can be in the know of a newspaper article and why they are aware of writing a message due to paying attention to the language used by people in a patterned way. It is through this understanding that it is through observing in a casual way that is subconscious. It explains why an individual may write down a message suitable for a specific situation without paying much attention to it because one has selected the kind of language to use that is necessary. Therefore, the question that comes to mind is how do we deal with writing unfamiliar texts? Corpus linguistic analysis brings to the fore the notion of analyzing texts through computer-aided tools to provide a view of language patterns all through the text from the perspective of a bird’s eye of a given pattern of language. Corpus relates to textual bodies and linguistic analysis, which primarily deals in examining patterns of language use.

Corpus analysis of the written language provides an analysis of a given text and systematically analyzes written language in line with patterns in many texts over time. In relating to corpus analysis, it is evident that texts provide meaning patterned through texts and contexts. Also, it is onerous to understand the patterns of language when we are poised to read and provide analysis of a single text at a given time. Primarily, corpus analysis of written language is effectively involved in examining the textual patterns within the bounds of a selected body of naturally produced texts, often through computer-aided tools, which facilitate the discerning, sorting, and calculation of large-scale patterns in a text. Various theories, such as the classical theory, have played a crucial role (Vicente 2). The empiricist version in the advocacy of this theory argues that it contains some observational atomic concepts, while the contemporary versions assume that the atomic concepts whereby the innate concepts include; the agent, cause, object, or even the path are primarily abstract. With this in mind, it suffices to maintain that this paper will explore the notion of lexical clusters, their meaning, and types within the bounds of written language analysis (Heng et al. 3). The paper will examine various types of lexical bundles, including grammatical and functional types and their sub-functions, categories, and examples to bolster understanding of this concept.