Objectives. The objective of this study is to analyse the literature review on the effects of female genital cutting on the physical health of victims. This systematic review also evaluates the existing policy to combat the spread of FGM and assist victims, majority of which are the Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups living in the United Kingdom.

Background. Many communities have immigrated to the United Kingdom from countries where FGM is practised. The UK’s local authorities might have younger girls and women with high exposure to such risks. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reveals that globally, approximately 8,000 girls undergo FGC daily (Rainbo, 2009). Whereas this procedure has been wide in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, it is now a worldwide issue because of the migratory nature of people and the ensuing displacement from civil wars. As such, this systematic review study aims to enlighten them about the effects of FGC on their health outcomes alongside the legal implications and to encourage health-seeking behaviours.

Research Method. This study adopted secondary research method because it is an extended review of the effects of female genital cutting (FGC) on physical health outcomes. It analysed 22 sources on FGC.

Findings. FGM exposes girls and women to multiple physical effects including sexual difficulties, maternal death, and bodily harm. Girls and women who have undergone FGC are living in “virtually every part of England and Wales.” The leading cases are in London. Other than London, areas such as Leicester, Slough, Manchester, Birmingham, and Bristol have high rates of FGC ranging from 1.2 to 1.6%. It is perpetrated by BAME groups coming from practicing countries including Africa and part of the Middle East. Irrespective of significant awareness, police continue to express dissatisfaction over the intelligence on the practice. They also indicate that prosecutions are hampered by the global FGC practices as well as the unwillingness of the victims to point out their perpetrating relatives.

Conclusion and Recommendations. FGM exposes girls to multiple physical effects inclusing sexual difficulties, maternal death, and bodily harm. Concerning the mandatory reporting, there is need to promote training and awareness particularly for the regulated experts before execution of responsibilities. This is partly because of the importance of collecting accurate data specifying the outcome of mandatory reports. Such information is crucial in determining whether girls and other victims are being protected

Educating the UK’s BAME about the Nature and Adverse Health Outcomes of Female Genital Cutting

Chapter One: Introduction

1.0.Introduction

The objective of this study is to analyse the literature review on the effects of female genital cutting on the physical health of victims. This systematic review also evaluates the existing policy to combat the spread of FGM and assist victims, majority of which are the Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups living in the United Kingdom. According to the WHO, Division of Family Health (1996), roughly 100 – 140m women and girls had been the victim several forms of female genitalia cutting (FGC) as of today ( WHO, 2013). Whereas the UK outlawed this practice in 1985, there are many incidences, which indicate FGC goes on with perpetrators hardly prosecuted. Close to 137 000 people in the UK are thought to have experienced FGC effects, which can include potentially life‐threatening conditions such as long‐term psychological sequela, hepatitis infection, HIV/AIDS, and sepsis. The Government of the UK was requested to outline measures to address persecution as well as interventions for FGC (Gubbin, Bayar, and Finlay, 2017). For such reasons, this study addresses the health complications of FGC and recommends best interventions the government can take for complete eradication.

1.2. Definition

FGC is also called Female Genital Mutilation (FMG), female circumcision, as well as referred by a term such as gudniin, sunna, tahur, halalays, and Megrez (NHS, 2017). McCauley and van den Broek (2019) define FGC as “all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injuries to the female genital organs, whether for cultural or other non-therapeutic reasons.” This practice is associated with severe health outcomes.

1.3. Problem of the Study

According to the NHS ENGLAND statistics, more than 1000 cases of female genitalia cutting (FGC) were recorded between April and June in this year in the United Kingdom. Most of the procedures employed reflect those performed many years ago in the country. As such, the United Kingdom is no stranger to FGC. While it remains an illegal practice, Female genital cutting is considered as an important ritual to most people in the UK. The practice contravenes the human right of an infant or youth (NHS, 2017). The root causes of FGC are embedded into a mix of social, religious and cultural factor within the cultures and families. For example, there is a belief that FGC is essential for maintaining tradition and increasing marriageability (Gibeau, 1998; Vissandjée, Kantiébo, Levine, & N’Dejuru, 2003; Yasin, Al-Tawil, Shabila, & Al-Hadithi, 2013). Whichever the reason, FGM is an indicator and the extremity of gender discrimination. Moreover, it attracts serious health complications. In the UK, the government is dedicated towards eradication of the practice.

Who are affected by the problem? The most risked groups are the immigrants especially the BAME groups who come from FGM practising communities. There is a need to enlighten these groups as well as the healthcare practitioners about the adverse health effects and legal implications of this practice.

FGM has severe health outcomes. The short term problems include bleeding, extreme pain, urinary retention, and adjacent tissue damage. It might also lead to long-term health effects, such as contributing to the transition of HIV (Moniok et al., 2007). Other long term effects comprise the inclusion cyst, abscesses, micturition and menstruation problems, pregnancy problems, injuries in vagina and pelvis and other psychosomatic and psychological problems. The risks of such problems increase with the severity of female genital cutting (Banks et al., 2006). Organisations such as 28 Too Many, African Women’s Organisation, United Nations, Daughters of Eve of the United Kingdom and many more are trying to fight FGM by giving social, medical and cultural support. Raising awareness about the adverse health outcomes of FGC is very important. This study analyses the literature review that discusses the effects of female genital cutting on the physical health of victims. It also evaluates the existing policy to combat the spread of FGM and assist victims of this practice in the United Kingdom. The next section focuses on the background and rationale of the study including the existing strategies or policies for FGM, it also aims and objectives, the methodology and search strategy, ethical considerations and project outline of the study.

1.4. Background/Context

How long FGC has been of concern. While FGC was practised in different cultures throughout history, however, its exact origin is yet to be discovered due to lack of evidence. The practice is thought to originate earlier before the rise of Islam and Christianity. According to research done by Lightfoot-Klein (1989), Arabs and early Romans must have practised FGC (Sheehan 1981, pp.9-15). Currently, the number of FGC victims each year is estimated to be 3 million (UNICEF, 2005). FGC is prevalent in 28 countries in Africa extended from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west. However, there could be considerable variations within those countries. The migrant communities throughout the world are also seen to practise it (WHO, 2000). The reasons and contributors to the practice of FGC are multifaceted and is different in different communities. Hosken has argued that many societies believe the uncircumcised woman to be unable to control sexuality and are most likely to bring disgrace to the family (Hosken 1993, p.40). Therefore, the elimination of that sensitive tissue is seen as a solution to reducing sexual desire. Proving the chastity and virginity of the girl and increasing her marriage prospect is thought to be one of the functions of FGC (WHO, 2000). Man’s sexual pleasure is also thought to be increased due to FGC applied to a female person (Toubia, 1995). FGC is also seen as a transition to womanhood in some communities. FGC is practised along with different religions including Muslims, Animists, Jews and Christians. Moreover, hygiene and aesthetics causes and myths also contribute to the culture of FGC.

Categories of FGC. The WHO typology classified FGC in four categories. The type I is also known as clitoridectomy, type II known as excision, type III known as pharaonic circumcision or infibulation and type IV. Type IV refers to all the remaining procedures of FGC. Type III, also called infibulation, is the worst form of FGC. It attracts critical health outcomes and accounts for 10% of cases (McCauley and van den Broek, 2019). By 2013, the WHO, Division of Family Health (1996) reported that roughly 100 – 140m women and girls had been the victim of several forms of female genitalia cutting (WHO, 2013). Currently, more than 200 million girls and women are victims of this practice globally (McCauley and van den Broek, 2019). Accordingly, FGC methods differ from community to community (UNICEF, 2020). In case of UK, since 2015, there have been 17330 survivors recorded. However, a study estimated that 137000 girls and woman who migrated to Wales and England are living with FGC.

Justifications for the practice. Communities practice FGC do so based on several justifications, which can be societal, religious or psychosexual based such as the promotion of chastity to uphold the family honour by control a woman’s sexuality. Others do so pointing to the religious practice for spiritual cleanliness and prevention of lousy odour (Rainbo, 2009). This practice is upheld in communities through community enforcement plans sustained by poems, songs, or ridicule to those not undergoing it. However, some practices are the preserve of the traditional communities, as modern societies employ more clandestine approaches.

Outcomes/Health implications. FGC is considered as a health and human rights issue. However, since is it fully integrated into cultural traditions, it poses many intervention challenges. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), FGC does not have any positive hygiene or health outcomes, neither can such reasons justify its practice. Instead, WHO considers it an act of violence and a form of discrimination against women (Rainbo, 2009). The practice has a substantial burden of cultural and social implication, with the possibility of medical and psychological outcomes. There is a widespread perception that incidence is lower in communities from practising countries who live in Europe, particularly in the younger girls, irrespective of uncertainty about quitting the practice because of it serving as a symbol of the country of origin. The truth is quitting the practice attracts severe social costs. According to Berer (2015); “If you asked African-born women in Britain, including those whom themselves have experienced FGM, whether they would allow their daughters to go through the same thing, some would say yes.” It does not mean they hate their daughters instead; abandoning such cultures attracts a high social cost from the specific communities.

FGC comes with serious health repercussions. From the research conducted by Berg et al. (2014) on “Effects of female genital cutting on physical health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, there are multiple physical health complications. In case of immediate complications, in most of the cases of FGC, a practitioner, who have no considerable medical knowledge about anatomy, could cut the girl’s clitoris and labia with a crude instrument that’s unsterile and without anaesthetics (Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: a statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change, 2013). The common immediate complications include urine retention, excessive bleeding, healing complications, extreme pain and genital tissue swelling (El Dareer, 1983). An FGC victim suffers from more than one complication at a time. According to Hosken and El Dareer, woman’s sexuality is influenced by FGC leading to difficult and painful intercourse and sexual experience (ElDareer,1981), and loss of satisfaction of enjoyment and sensation (Hosken,1993). It has also been evident that long-term genitourinary infections may result in reproductive tract infections, chronic pelvic infections (Almroth et al., 2005), vaginitis and genital infections. It has been postulated that FGC causes Dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse), higher risk of HIV and infertility (Berg et al., 2019). In the research by Berg (2014) and De Silva (1989), obstetric events (difficult labour, instrumental delivery, haemorrhage, episiotomy, tears/lacerations, and prolonged labour) were reported in case of 26 comparative studies conducted on 2.97 million women.

Interventions and Policies. The Government of United Kingdom addresses FGC through the lens of human rights. It acknowledges that the practice contravenes recognises various UK signatory acts and human rights provisions such as “the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1990), the European Convention on Human Rights (Art. 2 and 14), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Art. 1 and 3) and the Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (See Gill, 2016)” (Gangoli et al., 2018). For such reasons, the government considers FGC as a criminal offence outlawed under the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003. Perpetrators of this practice based on the 2003’s Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 are subjected to a 14-year imprisonment or fine. The government further refined this 2003 Act based on the Serious Crime Act 2015 adding more sections. Examples of include the establishment of a distinct offence of failure to safeguard a girl from FGC, provision of confidentiality for victims of FGM, extension of the extra-territorial jurisdiction for FGM, create FGC Protection Orders and “introduce a mandatory reporting duty requiring regulated health and social care professionals to report known cases of FGM in under 18s to the police” (Gangoli et al., 2018).

Some different interventions targeting community interventions have also been implemented. Several community-level organisations are working to protect girls from FGC. The communities that are most successful in this case are participatory and also guide people to understand, define and solve the problem themselves such as, Tostan’s Community Empowerment Program which is an informal education program based in Africa.UK has declared FGC illegal since 1985. The law was enforced with more effort to prevent girls from undergoing FGC abroad. In the UK, it is also illegal to fail to protect a girl from FGC. UK has also pledged to fund of 410 m dollars for children and social care to fight against FGC. Over the past decades, the commitment to tackle female genital cutting continued to grow internationally. For example, A World Fit for Children was a document that was the outcome of a special assembly for children held by the UN in 2002 (Dixon et al., 2018). The document called for the effort to end harmful customary and traditional practices such as FGC and child marriage. Some countries can achieve the given target while others can make huge advancements towards that aim if they are provided with sufficient resources. The global and international community never had this much understanding of the reasons for FGC prevalence and its growing.

Effectiveness of policies. Concerning the view of FGC under legal terms, the policies have not succeeding to making prosecutions for the offenders. Criminal agencies in the UK are embarked to address this condition at the local and national level. For instance, the first prosecution of a medical officer in the UK failed in 2015 for claims that the Crown Prosecution Service was only a exhibiting a practice based on political persuasion (Gill and Hamed, 2016). Three decades following the enactment of laws against the FGC, the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee explained their report as “beyond belief” that no single successful prosecution had been achieved. The inability to make the culprits to account for their actions have been curtailed by the absence of political will, stigma of reporting FGC, and the conspiracy with communities where suctions occur (Home Affairs Committee on FGM, 2016).

One of the effective policies deal with community and multi-stakeholder interventions. For instance, recent policy implications require the physicians, teachers and other regulated specialists to report directly to the police department concerning any claim of any first-hand disclosure to FGC by females below the age of 18years (Dixon et al., 2018). This law also requires the England NHS health agencies to submit data to NHS Digital dealing with younger girls and women at risks or who have experienced FGC

Barriers to change. Eradication of FGC has multiple impediments including the underreporting of cases. Majority of the victims are children who may fear to report the perpetrators. In most cases, the culprits are parents of such children thus most are reluctant to report. Accordingly, the cultural ties that consider FGC as a rite of passage for marriage implies that most girls are ready to accept the practice. At the same time, girls may view the practice from a religious perspective thus justifying it. Globally, many religious leaders justify FGM irrespective of lack of sufficient ground for moral support by most of all of the religious scripture (World Health Organization, 2013). As Gubbin, Bayar, and Finlay (2017) report, more than 350 faith leaders signed a declaration in 2014 to reduce such as an FGC religious incentive.

Furthermore, the fear due to stigma can prevent most of the victims from reporting FGC. For such reasons, the 2015 legislation integrated a lifetime anonymity for victims. The country also established a confidential and free “National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) helpline” to reach more victims and encourage reporting (Gubbin, Bayar, and Finlay, 2017). NSPCC supplied victims with email contact such that by June 2013, it received 1200 contacts. More than a third of these contacts were referred to the children’s or police services.

1.5. Project Rationale/Justification

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reveals that globally, approximately 8,000 girls undergo FGC daily (Rainbo, 2009). This figure translates to more than 3 million females being subjected to the practice each year. Whereas this procedure has been wide in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, it is now a worldwide issue because of the migratory nature of people and the ensuing displacement from civil wars. An increasing number of female who experienced FGM currently stay in Europe, particularly the United Kingdom and other western countries. This procedure predisposes young girls to dangers especially when their family seeks to uphold such practices irrespective of the regulations the forbid it.

As Dixon et al. (2018) reveal, there is a paucity of studies on the effects of FGM on women and communities in the United Kingdom. Little is known concerning the affected communities’ understanding and knowledge of these new legal implications, as well as their readiness to disclose and reveal to the physician. Similarly, no studies reveal the comprehension level of healthcare experts. As such, this study is integral for informing the immigrant communities in the United Kingdom about the risks and policies of FGC as well as equipping the medical practitioners with knowledge regarding the issue.

This study contributes to the current efforts to eradicate this social and health problem from the root source. To do this, the proper identification and awareness about the effects of FGC on physical health outcomes are necessary. Once the issue is clear to people, including its effect on the victim, it can enable them to prioritise the remedial action. Such measures can also help in proper treatment and health intervention for FGC victims. There has been a lot of research on FGM by Jungari (2015), Rose Ansorge (2008), Berg (2014), Banks (2006), Dareer (1981) etc. But there has always been debate about different physical health outcomes. Such as, Dareer (1981) argues that FGC causes STD and HIV, infertility and genitourinary problems. Whereas, Berg (2014) failed to establish a clear relationship between these diseases and FGC in “Effects of female genital cutting on physical health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. So, it is a pressing need to clear these doubts to help in social and medical interventions to prevent FGC and help the victims. This justifies the need for an extended literature review exploiting the effects of female genital cutting on physical health outcomes.

1.6. Aim and Objectives

Many communities have immigrated to the United Kingdom from countries where FGM is practised. The UK’s local authorities might have younger girls and women with high exposure to such risks. As such, this systematic review study aims to enlighten them about the effects of FGC on their health outcomes alongside the legal implications and to encourage health-seeking behaviours.

The objectives of the study include:

- To discuss the prevalence of female genital cutting globally and locally.

- To establish the awareness of FGC by BAME immigrants and healthcare professionals including the root causes.

- To investigate the effects of FGC on physical health outcomes of the BAME groups in the UK.

- To determine the effectiveness of the mandatory reporting policy as well as to report other international policies on tackling FGC among the BAME groups in the United Kingdom.

Chapter Two: Methodology

Research Method

This study adopted secondary research method because it is an extended review of the effects of female genital cutting (FGC) on physical health outcomes. The two major types of secondary research strategies include the systematic review and narrative review. A narrative review is descriptive and does not systematically conduct searchers across databases. Critical analysis of the present literature and articles is done in case of narrative review.

The education sector is greatly indebted to narrative review articles because these articles contain the up-to-date evaluation of an issue. Even though, there are some setbacks. In a narrative review, a subset of a topic is highlighted and the selection of articles relies on the availability of author selection and researches (Pai et al., 2004). That’s why it is not free from selection bias. Moreover, at times, diverging outcomes and conclusions make the narrative reviews confusing (Liberati et al., 2009). On the contrary, in the case of the systematic review, comprehensive and detailed plan for searching among the literature databases is done (Liberati et al., 2009). Despite being published in academic forums, systematically reviewed articles are promoted and disseminated in several other organisations and databases. However, the study follows the method of the narrative review. It is because the theme of an extended review resonates with the critical analysis which is a core characteristic of narrative review. For the rationales and reasons mentioned above, a narrative review method has been selected to carry out the research.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

Keywords and search terms. One of the very first tasks of the literature search strategy is to determine search terms and keywords that can guide the literature selection across the databases. In this study, the topic is structured in PCO framework to determine search terms and keywords for the review. Moreover, the researcher used the Boolean operators AND, OR, NOT to establish connections between the terms. The question were first designed into the PCO framework and connected with Boolean operators as shown below.

Table 1: Keywords and Search Terms for Literature Search Strategy

| Population | Boolean operator | Context | Boolean operator | Outcome |

| Female |

AND/OR

|

Genital cutting |

AND/OR/NOT |

Physical health outcome |

| Girl | Circumcision | Health | ||

| Woman* | Genital mutilation | Pain | ||

| Lady* | Clitoridectomy | Physic* | ||

| Genital excision | Risks | |||

| Genital modification | Disease | |||

| Infibulation | Harm | |||

| ‘*’ sign indicates truncation | ||||

These search terms and keywords are to be used to search for relevant articles and literature in different databases and sources. However, the researcher uses the Boolean operators named as OR, AND and NOT in guiding the search terms and literature search. It is to be noted that these operators narrow down or broaden the search. Whereas, AND and NOT narrow down the search. Such as, if the search is strategised as female AND genital cutting NOT pain. Then, the search results included keywords female and genital cutting both but excluded keyword pain. And in case of truncation ‘*’ indicator, it implies all the words that begin with the word with the truncation.

2.2. Literature Search Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This research collected the literature and articles from various available databases. However, the search results are subject to exclusion and inclusion criteria as the search integrated thousands of literature and articles on the same topic. To sort out the most representative and appropriate literature from others, the researcher thus employed several exclusion and inclusion criteria as demonstrated in the following table.

Table 2: Literature Search Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Criteria | Justification |

| Studies published between 1980 and 2019 | The study will enlighten the BAME groups as well as the healthcare specialist about the effects of FGC on their health outcomes alongside the legal implications and to encourage health-seeking behaviours. So, studies from late 19th centuries also are included here since it is not just a recent problem but not earlier than that because of the lack of medical advancements in earlier times as the study focuses on physical health outcomes. |

| Studies that examined the effects of FGC on physical health outcomes | Determining the effects of female genital cutting on physical health outcomes is one of the aims of the study. As such, the research integrated the studies focusing on examining the effects of FGC on physical health outcomes. |

| Studies highlighting the contributors and causes of FGC | As this research examined the causes and contributors of FGC to fulfil the objectives, studies that have focused on contributors and causes of FGC were included. |

| Literature discussing the policies and strategies to tackle FGC | The policies and strategies that are taken by different govt. or non-govt. organisations to tackle the FGC problem is one of the major discussion points of the study. And, it is also very important to be clear about to recommend the things to be done to eradicate FGC from society and support the present victims from different angles. |

| Studies that were based on primary data | No literature review studies of narrative or systematic approach are to be selected in the final list of literature. Because primary research provides the data collected directly from subjects. Moreover, an in-depth view of the issue is provided in case of primary data. That allows the researcher to discover new findings from the study. That’s why studies based on the primary data are included in the final review. |

| Studies published in the English language | Due to the deficiency of resources for translating foreign languages into English, only the literature published and written in the English language is selected. |

Databases Selected for Literature Search

Concerning the narrative review, it is necessary to carry out a comprehensive search in different databases. For this research, ProQuest, Emerald Insight, ScienceDirect, Scopus, PsycINFO, PubMed, CINAHL, OVID, MEDLINE, Cochrane, JStor and ResearchGate are the main databases in conducting the comprehensive search as these databases are enriched with a wider selection of literature and articles. Peer-reviewed high-quality articles and journals are found on the databases outlined above.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are an important part of any research. This research is an extended literature review which can be categorised as secondary research involving narrative review. Thus, the study does not involve primary participants. As such, the research does not adhere to strict codes of conduct required for the primary research. Nonetheless, several ethical issues require complete compliance while conducting the secondary research and analysis of data. The main concerns about secondary research are the disclosure of coded information, falsification, and misinterpretation of data (Thome, 1998).

In case of access to the coded information, the researcher avoided identifying key information from the secondary data such as the names of participants. Moreover, ethics in secondary research and analysis requires the adoption of relevant, adequate but not excessive information. Since the research does not depend on the primary source of data (participants), hence, the data obtained must be evaluated in perspective of the aim, methodology, the accuracy of the primary information (Thome, 1998). Therefore, the research must be free from falsification and misinterpretation of data. The information obtained also should not be kept longer than necessary. The researcher must ensure the security and privacy of the data held.

This research reviews only the journals or articles that have received the clearance from the board in case of ethics. It would also be careful to avoid identifying information through anonymity or pseudonyms. The research adhered to the scholarly practice, integrity, respecting rights, dignity and diversity. The study was free from plagiarism, falsification and misinterpretation of data and proper references would be shown concerning the authors and sources. The UK government has pledged 410 m dollars for child and social care to fight against FGC. On the contrary, the local govt. said it to be not enough which shows the negligence of the govt. for the issue. In many countries, FGC is allowed by the government but it is also a clear violation of human rights. Therefore, the tension between universal laws and national laws arose. In issues like these, the study surely would maintain neutrality and give conclusions or review from an objective point of view.

2.4. Project Outline

This research contains four chapters. Chapter one focuses on the introduction, background and rationale, aim and objectives. This chapter introduces the topic and offer a justification for the study. Chapter two presents the methodology, which discusses data search strategy, exclusion and inclusion criteria and ethical considerations. Chapter three presents the results of literature reviews and the discussion. Relevant literature is also discussed to fulfil the aim of the study aligned with the objectives as well as the discussion and findings in this third chapter. The last section (chapter four) presents the conclusion, recommendations, and policy implications of the study.

Chapter Three: Results

3.0. Introduction

This study drew results from 20 sources which are: (Cockroft, 2015); Dearden, 2018);(Owen, 2012); (Dorkenoo, 2018);(Norris, 2019); (Thompson, 2020; (City University, 2012); (Dearden, 2019); (Proudman, 2019); (BBC, 2019); (Standard, 2014); (Ali et al., 2020); (Chung, 2016); (Berg et al., 2014); (Kerubo, 2010); (Rigmor Berg and Vigdis Underland, 2013); (Weebly.com, 2013); (Berg and Denison, 2013); (London Safeguarding Children Partnership, 2017); (Adam et al., 2019). Results were presented ategorically based on the four study questions in the order of prevalence, awareness, effects, and the effectiveness of mandatory reporting and other interventions.

3.1. Prevalence

Concerning the prevalence of female genital cutting globally and locally, seven studies provided the findings. They include (Cockroft, 2015); Dearden, 2018); (Owen, 2012); (Dorkenoo, 2018); (Norris, 2019); and (Thompson, 2020; (City University, 2012). The summary of the findings are grouped based on the data presented in tables below.

Table 3. FGC recorded by NHS England/yearly reports

| Region | Newly recorded April 2015-June 2019 | Newly recorded April-June 2019 |

| East of England and Midlands | 3,908 | 270 |

| London | 8,203 | 375 |

| North of England | 4,204 | 250 |

| South of England | 1,703 | 80 |

| Total | 21,510* | 975 |

* Source: Norris, 2019. Data drawn from NHS England.

Table 4. FGC in the UK based on reported yearly reports

| Nation | FGM cases |

| England April 15-June 2019 | 21,510 |

| Wales 2016-2018 | 465 |

| Scotland 2017-2018 | 231 |

| Northern Ireland 2016-2018 | 22 |

| Total | 22,228 |

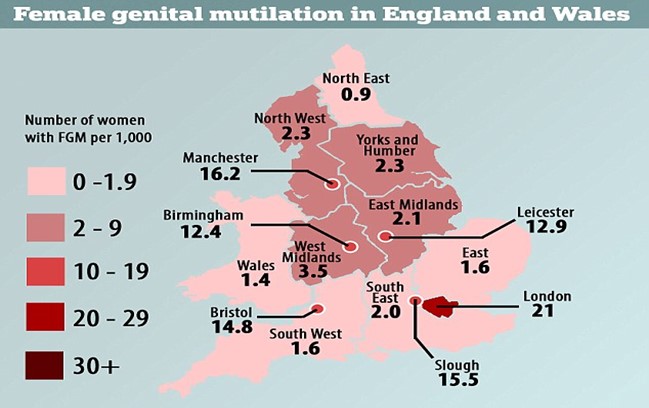

Figure 1. Victims of FGC in England and Wales

The graph above indicates that victims of FGC stay almost in every location of Wales and England, with London having the highest rates.

Figure 2. Average number of reported FGC incidences in London.

The graph above represents the average number of reported FGC incidences in London. More than 137,000 victims are affected by FGC across the country. London’s borough of Southwark has the highest rates.

| Country | Estimated population with FGM |

| Italy | 59,716 |

| France | 53,000 |

| Germany | 47,359 |

| Sweden | 38,939 |

| The Netherlands | 29,120 |

| Belgium | 17,273 |

| Norway | 17,058 |

| Spain | 15,907 |

| Finland | 10,254 |

| Location | Current Victims |

| Europe | 700,000 |

| UK | 140,000 |

| France | 100,000 |

| USA | 500,000 |

Table 7. FGC in African countries

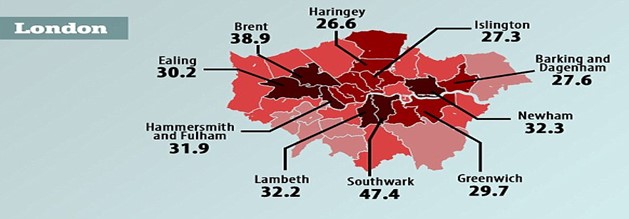

Figure 3. FGC prevalence (%) among girls and women aged 15 to 49 year in practicing countries.

Source: UNICEF 2020

Table 8. The distribution across countries in numbers

| Countries | Population of FGM girls/women |

| Egypt | 27.2 million |

| Ethiopia | 23.8 million |

| Nigeria | 12.1 million |

| Sudan | 19.9 million |

| Kenya and Burkina Faso | 9.3 million |

| Mali and United Republic of Tanzania | 7.9 million |

| Guinea and Somalia | 6.5 million |

| Côte d’Ivoire and Yemen | 5.0 million |

| Chad and Iraq | 3.8 million |

| Eritrea and Sierra Leone | 3.5 million |

| Senegal, Mauritania and Niger | 3.4 million |

| Liberia, Cameroon and Benin | 2.7 million |

| Gambia, Ghana and Central | 1.3 million |

| Guinea-Bissau, Djibouti, Uganda and Togo | 919,000 |

3.2. Awareness of FGC by BAME immigrants and healthcare professionals

The awareness of FGC by BAME immigrants was reported by eight sources which comprise (Dearden, 2018); (Norris, 2019); (Thompson, 2020); (City University, 2012); (Proudman, 2019); (BBC, 2019); (Standard, 2014); and (Ali et al., 2020).

3.2.1. Summary of the Awareness Results

- Men’s views on FGC are mixed. They do not see FGC as okay is usually imagined. Since the practice is not discussed openly between women and men, there is a gap across their interpretations and expectations.

- Girls may be circumcised against their parents’ will, typically at the wish of their grandmothers. Stories were reported of girls being sent ‘back home’ to be circumcised, often following significant pressure from family and/or the wider community.

- Immigration can alter attitudes, especially when people have passed across countries that have solid advocacy on a rights. For instance, immigrants who passed through the Netherlands were highly opposed to FGC.

- Other views regarded FGC as being practiced in the UK.

- Whereas some women can oppose FGC, they can hardly resist the practice. As such, most of the respondents suggested that there is much work to be done to curb FGC applying more stringent enactment of the law or increasing awareness and learning campaigns to the masses.

- The appropriate age for girls’ exposure to FGC is not limited to the pre-teen age but also as far as 21 years or the late teen period.

- Perceptions towards the law are changing. Previously, FGM was thought to be a deterrent. Currently, the absence of prosecutions makes inhibits advocates to use the law as an argument.

- For the targeted groups, views against FGC are largely focused on the negative health disorders instead of the rights of children and women. Such a standpoint inhibits the ability to create policies against type 1 FGC and the type conducted using painkillers and within a hospital setting.

- Some respondents expressed dissatisfaction voicing the issue of double standards concerning the legality of labiaplasty and male circumcision and also

- There is a considerable change in the actual practice of FGC. More respondents favour Types I and/or II over Type III.

- There have been frequent campaigns set up in the UK to curb the practice.

3.3. Effects of FGC on Physical Health Outcomes of the BAME Groups

The researcher utilized five articles to determine the effects of FGC on the health of culprits. They include (Chung, 2016); (Berg et al., 2014); (Kerubo, 2010); (Rigmor Berg and Vigdis Underland, 2013); Kinyua et al., (2014). Based on some of the sources used, factors such as religious affiliations, level of education, residence settings, and respondents’ age were considered in selecting participatnts who would have encountered FGC. One of the studies integrated, Kinyua et al. (2014), examined 407 participants (girls), out of which 122 girls were aged 25-30 years, 244 aged 20-24 years, and41 aged 14-19 years. The study also selected 46 health workers who would provide supplementary information on effects of FGC on the physical health of girls. The selected participants were from Kenyan context, with a distribution of 54.3% female and 45.7% male. To assess Physical Health Effects of FGC, this research utilized three key indicators of “Sexual difficulties, maternal health, and Bodily harm and infections.”

3.3.1. Perception of Girls’ on Physical Health Effects Related to FGC

The data below was drawn from Kinyua et al. (2014) study regarding the girls’ perceptions on physical health effects of FGC. The researcher evaluate the SD based on 5 point Likert Scale starting with Strongly Agree = 5 to Strongly Disagree = 1.

| Sexual Difficulties Related to FGC | N | M | SD |

| FGC practice causes me to have regrettable sexual memories | 407 | 3.6739 | 1.31748 |

| FGC practice causes me to be sexually dysfunction | 407 | 3.6757 | 1.08436 |

| The practice of FGC causes me to encounter painful sexual intercourse | 407 | 3.6261 | 1.16124 |

| FGC limits my sexual satisfaction | 407 | 3.9500 | 1.11555 |

| After I undergo FGC, I do not experience sexual arousal | 407 | 3.7121 | 1.24762 |

| FGC causes my genitalia to be dry and post-coital bleeding | 407 | 3.2961 | 1.24050 |

| Overall Mean and Standard Deviation on Sexual Difficulties Responses | 3.7572 | 0.85483 | |

| Maternal Health Issues Related to FGC | |||

| FGC causes my urinary and menstrual problems | 407 | 3.0161 | 3.30840 |

| FGC causes my child birth complications | 407 | 3.6813 | 1.22417 |

| FGC makes me have difficult with gynecological examinations | 407 | 3.2079 | 0.98256 |

| FGC is a source of my recurrent reproductive tract infections | 407 | 3.0725 | 1.1146 |

| FGC has caused death to some of my friends | 407 | 3.4130 | 1.118 |

| FGC limits my contraceptive choices | 407 | 2.8387 | 1.0772 |

| Overall Mean and Standard Deviation on Maternal health Issues Responses | 407 | 3.4094 | 0.85830 |

| Bodily Harm and Infections Related to FGC | |||

| FGC made me suffer from severe Anaemia | 407 | 3.8280 | 1.06900 |

| Am worried that FGC may transmit STIs and HIV/AIDS infections to me | 407 | 4.0835 | 1.08182 |

| FGC led to my urethra and bladder damage | 407 | 3.1057 | 1.25205 |

| FGC exposed me to tetanus infection | 407 | 2.8649 | 1.27264 |

| FGC leads to growth of keloid scars around the genitalia | 407 | 3.8501 | 1.30477 |

| FGC damages girl’s urethra and bladder | 407 | 3.1522 | 1.29901 |

| FGC made me experience urine retention due to pain, swelling and blocked urethra | 407 | 3.2727 | 1.31375 |

| FGC has made me to suffer from painful and blocked menses | 407 | 3.2948 | 1.20408 |

| Overall Mean and Standard Deviation on Bodily Harm and Infections Responses | 3.5372 | 0.80339 | |

Source: Kinyua et al., 2014.

3.3.2. Perception of Health Workers on Physical Health Effects Related to FGC

The data below was drawn from Kinyua et al. (2014) study regarding the health workers’ perceptions on physical health effects of FGC. The researcher evaluate the SD based on 5 point Likert Scale starting with Strongly Agree = 5 to Strongly Disagree = 1.

| Sexual Difficulties Related to FGM | N | M | SD |

| FGM practice is a source of regrettable sexual memories | 46 | 3.6739 | 1.31748 |

| FGM practice leads to sexual dysfunction among the girls | 46 | 3.6957 | 1.31436 |

| The practice of FGM results to painful sexual intercourse | 46 | 3.8261 | 1.08124 |

| FGM limits a girls’ sexual satisfaction | 46 | 4.0000 | 1.11555 |

| Girls who have undergone FGM experience no sexual arousal | 46 | 3.8261 | 1.28762 |

| FGM causes genitalia dryness and post-coital bleeding | 46 | 3.3261 | 1.30050 |

| Overall Mean and Standard Deviation on Sexual Difficulties Responses | 3.7836 | 0.96983 | |

| Maternal Health Issues Related to FGM | |||

| FGM leads to urinary and menstrual problems | 46 | 2.8261 | 1.33840 |

| FGM causes child birth complications | 46 | 4.3913 | .80217 |

| FGM results to difficult gynecological examinations | 46 | 3.7609 | 1.28556 |

| FGM is a source of recurrent reproductive tract infections | 46 | 2.9565 | 1.19176 |

| FGM is a contributory factor to maternal death | 46 | 3.9130 | 1.13188 |

| FGM limits contraceptive choices | 46 | 2.6087 | 1.4972 |

| Overall Mean and Standard Deviation on Maternal health Issues Responses | 46 | 3.4094 | 0.85830 |

| Bodily Harm and Infections Related to FGM | |||

| Girls involved in FGM suffer from tetanus 46 | 46 | 2.7609 | 1.09919 |

| Girls who have undergone FGM suffer from severe anaemia | 46 | 3.6522 | 1.19661 |

| FGM facilitates transmission of STIs and HIV/AIDS infection | 46 | 4.4130 | .97925 |

| FGM excessive bleeding and infected wounds often cause death | 46 | 4.2174 | .84098 |

| FGM leads to growth of keloid scars around the genitalia | 46 | 3.8261 | 1.30477 |

| FGM damages girl’s urethra and bladder | 46 | 3.1522 | 1.29901 |

| FGM results to painful or blocked menses | 46 | 2.8478 | 1.36573 |

| FGM causes urine retention due to pain, swelling and blocked urethra | 46 | 3.2727 | 1.31375 |

| Overall Mean and Standard Deviation on Bodily Harm and Infections Responses | 3.4946 | 0.78879 | |

The above data shows the health worker’s responses regarding physical effects of FGC.

3.3.3. HIV and sexually transmitted infections

Most of the authors (They include Berg et al. (2014), Hyojin et al. (2019), Berg and Underland (2014), Kinyua et al. (2014), Kerubo (2010), and Kinyua et al. (2014) agreed that FGC exposed victims to multiple infections including HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

3.3.4. Child birth and sexual complications

Several studies reported on childbirth issues including infertility and obstetric events such as prolonged labour, caesarean section, episiotomy, haemorrhage, tears/lacerations, difficult labour, and instrumental delivery. They include Berg et al. (2014), Hyojin et al. (2019), Berg and Underland (2014), Kinyua et al. (2014), Kerubo (2010), and Kinyua et al. (2014).

3.4. Effectiveness of Interventions and Mandatory reporting

Four sources reported about the effectiveness of mandatory reporting and existing interventions. They include (Weebly.com, 2013); (Berg and Denison, 2013); (London Safeguarding Children Partnership, 2017); (Adam et al., 2019), (Dearden, 2018), Dorkenoo (2018), (Cockroft, 2015); (Neelam, 2016).

The summary of studies on the proposed mandatory duty/reporting based on Home Office as indicated by several authors include:

- Application of mandatory reporting is to work in instances of “known” FGC, particularly those revealed by the victim and which could be visually confirmed.

- Mandatory reporting is limited to victims under 18. According to the government, there is ongoing consultations as to whether to allow views and concerns from adult women since an absence of such could prevent them from obtaining medical advice and help.

- It can apply for the teachers and all regulated social care and healthcare experts.

- All reports are to be submitted to the police within one month of the initial identification/disclosure. Based on the instances of the issue, it might not essentially trigger automatic arrests.

- The inability to adhere with this duty would attract penalty via existing disciplinary actions such as being referred to a professional regulator.

Chapter Four: Discussion

4.0. Prevalence

Most of the FGC occurs in Africa and Middle Eastern countries, which regard it a cultural practice meant to preserve chastity. Countries such as parts of Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia force more than 90% of their girls to undergo the practice. Based on the findings by Cockroft (2015), girls and women who have undergone FGC are living in “virtually every part of England and Wales.” The leading cases are in London. Around 140, 000 girls and women are affected by FGC in the UK. Southwark borough of London has the highest rate majorly because of the ethnic composition of people from FGC practicing backgrounds. In Southwark, at least one in every 20 women and girls (4.7%) has been a victim of FGC. Accordingly, at least one in ten of their mothers have also undergone FGC. This finding is supported by Dearden (2018) which reveal that since 2015, more than 17,330 cases of FGC survivors cases were reported, yet more than 137,000 girls and women who migrated to the UK were exposed to the effects of this procedure. By 2012, Owen (2012) reports further that around 6000 girls in London experienced this procedure while at least 22,000 also underwent it in the United Kingdom.

Other than London, areas such as Leicester, Slough, Manchester, Birmingham, and Bristol have high rates of FGC ranging from 1.2 to 1.6%. Cockroft (2015) quotes the recent survey by Equality Now, a human rights agency and City University London, which indicate that other cities such as Oxford, Northampton, Milton Keynes, Thurrock, Reading, Sheffield, Cardiff, and Coventry as having high rates as much as 0.7% or more.

Most of the ethnic minorities in UK coming from FGM practicing countries tend to stay in urban places. Irrespective of this, there is no local authority exempted from this practice. Cockroft (2015) further quotes the recent research by the Home Office and Trust for London, which examined the birth data from the Office for National Statistics. This research builds on the survey created in 2014, which indicated an average 137,000 girls and women affected by FGC as having a permanent residence in Wales and England in 2011. This report also highlighted higher rates in London and other big cities. There were also cases of FGC dispersed across the country with an overall rate of 1.6%.

Whereas the practice is prohibited in most of the African countries and the developed world, FGC is present across thousands of families that fear being ejected should they fail to submit their girls to the practice as a cultural component. The survey by Cockroft (2015) further informs that at least one million women and girls have been exposed to FGC effects in North America and Europe. More than 700,000 currently victims live in Europe. The United Kingdom alone has at least 140,000 current victims while France has 100,000. The United States has more than 500,000 women and girls who have experienced FGC. It is also feared that more than 65,000 British girls are at dangers of being transported to their motherlands especially in Africa or some parts of Asia to undergo FGM. Those at high risks are in ages of 12 and 13.

4.1. Awareness of FGC by BAME immigrants and healthcare professionals

One of the findings by Dearden (2018) presents case studies based on awareness campaigns to determine FGC prevalence in the UK and curb it. According to the report, they set up the campaign in consultation with FGM survivors and groups such as The Girl Generation and IKWRO, Midaye Somali Women’s Network, Forward UK, and the NSPCC.

“Let’s Protect Our Girls,” a campaign launched by The Home Office, focused on the parents and community elders in practising communities especially from Somalia, Gambia, Sudan, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Iraq. According to the spokesperson John Cameron, NSPCC head of helplines, awareness campaign reports alongside the received calls indicated that FGC continued to penetrate across thousands of girls in the United Kingdom. Nonetheless, the rate of exposure is still unknown since the practice has been cloaked in secrecy. John Cameron indicated that, “We hope this campaign will help to end the silence that surrounds FGM by encouraging young people and any adults worried about them to speak out and get help. By joining forces across communities, we can bring an end to this dangerous and illegal practice” (Dearden, 2018).

Irrespective of such significant awareness, police continue to express dissatisfaction over the intelligence on the practice. They also indicate that prosecutions are hampered by the global FGC practices as well as the unwillingness of the victims to point out their perpetrating relatives.

4.2. Effects of FGC on Physical Health Outcomes of the BAME Groups

4.2.1. Perception of Girls’ on Physical Health Effects Related to FGC

Sexual difficulties. Concerning the girl’s responses on sexual difficulties, the SD was 0.85453 with a mean of 3.7572. The maximum mean score was 5 points. This implies that the victims were moderately exposed to undergoing sexual difficulties such as rare orgasm, post coital bleeding, not enjoying sex, pain, and dryness during sexual activity. Whereas most victims were young to have encountered sexual intercourse, majority of them asserted that FGC had negative effects on sexual affairs including the effect of low sexual arousal, sexual dysfunction, and lack of sexual satisfaction. Such opinions correlate with the study by Berg and Underland (2014); Berg et al. (2014); and Kinyua et al. (2014), which indicate that FGC causes pain during sexual activity, reduces organism, and satisfaction. Partly it is because of destruction of nerve endings or the removal of sexually responsive vascular tissue that cause sexual excitement.

Overall, the SD and mean of initiated girls’ responses about maternal health difficulties were respective 0.78651 and 3.1536, which suggests that most of the victims were unsure whether maternal health difficulties were caused by FGC, possibly since most girls could not have given birth yet thus not having experienced maternal health difficulties. Nonetheless, the higher mean scores revealed that FGC led to child birth disorders like maternal deaths. Such perceptions align with those of Berg and Underland (2013) suggesting that maternal death most result from excessive bleeding from FGC scars. Such complications could also lead to obstetric disorders such as bleeding, obstructed and prolonged labour. As for the bodily harm, the overall mean and SD were 3.5372 and 0.80339 respectively. The implication is that most girls encountered moderate body harm following FGM procedure. Whereas not all people encounter painful complications after encountering FGC, however, Kinyua et al. (2014) posted that it would expose most victims to infections such as tetanus and HIV/AIDS. FGC exposes girls to unhygienic conditions that further exacerbate their health conditions.

4.2.2. Perception of Health Workers on Physical Health Effects Related to FGC

The overall mean of the reactions regarding the physical effects of FGC according to health workers was 3.7826. The corresponding standard deviation was 0.96983. The maximum mean score was 5 points. The implication is that most girls encountered moderate sexual difficulties following an FGC procedure. Such a response correlates with those of the girls who underwent FGC, which indicates that health workers concurred that FGC reduced the girl’s sexual arousal and satisfaction (Kinyua et al., 2014). They also intimated that FGC caused regrettable sexual memories, post coital bleeding, and genitalia dryness.

As reported by Kerubo (2010), FGC is also accompanied by extreme pain and traumatic stress as well as severe infection resulting from the tools used. It might also lead to complications in labor and painful periods, painful sexual intercourse, and severe bleeding neighboring organs as well as injury to such organs. The study further reveals that FGC could lead to permanent, irreparable changes in the external female, which would possibly alter the sexual processes.

The responses by health workers on maternal FGM effects was 3.4094. The SD was 0.85830 while the maximum mean score was 5 points. Such findings indicate that FGC compromises maternal health of the victims, which corroborates findings by Abor (2006) and Berg el al. (2014), which reveal that FGC might deform the female genitalia thus leading to caesarean problems and accompanying distress.

Concerning the bodily harm, mean response from the health workers was 3.4946 while the SD was 0.78879. The maximum mean score of 5 points. While this indicates that health workers were not highly satisfied about the bodily harm, the high mean scores reveal that victims cou ld encounter infections such as anaemia due to bleeding as well as the sexually transmitted infections such as HIV as supported by Kerubo (2010).

4.3. Interventions and Mandatory reporting

4.3.1. Interventions

Most of the women who undergone FGC are from the BAME communities staying “virtually every part of England and Wales.” As such, Cockroft (2015) recommends that support be advanced for such individuals during pregnancy and childbirth. More aid is required for older women due to the long-term complications of FGC.

Ms Anita Lower, the Local Government Association’s lead on FGC in UK, objects the torture children undergo at a time when they should be transiting comfortably to adult life. She narrates that no girl or young woman should be subject to the pain of FGC, which is tantamount to child abuse (Dearden, 2018). According to this report, charities, NHS, police, and councils are currently collaborating to stamp out this procedure. However, this stretches stretched children’s services department to the level that calls for more interventions. Ms Anita Lower narrates that “Long-term funding for the National FGM Centre is also needed for its vital, specialist work in communities to prevent FGM in the first place, and to develop expert knowledge to build relationships with families which can safeguard against this horrific kind of assault” (Dearden, 2018).

To successfully eradicate FGC, Dorkenoo (2018) states that a synergy of actions is required, including collaborations between the civil society and government. This integrates “community education, protection measures, justice outcomes and the provision of services to address the health complications” (Dorkenoo, 2018). Furthermore, Mary Wandia, FGC programme manager at Equality Now, recommends that policy makers across all levels collaborate to address the increasing levels of FGC. They can unite to prevent FGC and also by “protecting girls at risk, providing support to survivors, pursuing prosecutions when necessary and continuing to develop relevant partnerships, to ensure that all work to end this human rights violation is ‘joined up’ and effective at every level’” (Cockroft, 2015).

4.3.2. Mandatory Reporting

UK’s former Prime Minister David Cameron declared the intention of the country to create a mandatory reporting duty for FGM during the 2014 Girl Summit. Consequently, the policy was enacted through s 74 of the Serious Crime Act 2015. The act integrated a novel s 5B in the 2003 FGM Act. This new mandatory reporting duty “applies to regulated professionals, namely teachers, social care workers and healthcare professionals working in England & Wales. The personal mandatory reporting duty, for example, would not extend to dinner ladies, cleaners or caretakers working within the various environments” (Neelam, 2016). Nurses, doctors, and teachers have a mandatory responsibility to submit possible incidences of FGC according to this provision. This duty is meant to assist police conduct investigations against the practice and improve prosecutions.

Whereas mandatory reporting is essential, Dearden (2018) revealed that the “mandatory reporting procedures brought in for health workers, social care agencies and teachers have been “more symbolic than effective” (Dearden, 2018). Accordingly, there are confusions regarding the duty of data collection. Based on the suggestions by the Select Committee, “a centralised system for pooling reports of FGM would also be a positive step and would aid data analysis from which examples of best practice could be drawn” (Neelam, 2016). Furthermore, due to the lack of training of health, social care and education professionals, the execution of mandatory duty responsibilities might face significant hurdles.

4.4. Conclusion and Recommendations

Whereas the practice is prohibited in most of the African countries and the developed world, FGC is present across thousands of families that fear being ejected should they fail to submit their girls to the practice as a cultural component. More than 700,000 currently victims live in Europe. The United Kingdom alone has at least 140,000 current victims. Most girls encountered moderate sexual difficulties following an FGC procedure. Such a response correlates with those of the girls who underwent FGC, which indicates that health workers concurred that FGC reduced the girl’s sexual arousal and satisfaction

Most of the survey and case studies on awareness recommended the focus on research on FGC to also consider the attitudes but not just be on numbers. Significant researches focus on Sudanese, Somalis, and Kenyans communities. There is need to widen researchers to cover the under studied communities who have settled in the UK coming from backgrounds with high prevalence of FGC such as Ethiopia (74.3%), Eritrea (88.7%), Gambia (78.3%), Sierra Leone (94%), and Egypt (95.8%). Findings on the community based studies is vital to the establishment of targeted interventions designed for various groups. Accordingly, planning services should target and fulfil the needs of FGC to establish if there is a need for child protection for their girls. For such, there is need to find out the diversity/demographics of each BAME member and evaluate their needs from a personal level.

Concerning the mandatory reporting, there is need to promote training and awareness particularly for the regulated experts before execution of responsibilities. This is partly because of the importance of collecting accurate data specifying the outcome of mandatory reports. Such information is crucial in determining whether girls and other victims are being protected.