Teachers’ Perspectives on Implementing Guided Reading in Early Grades on Reading Comprehension

Abstract

The purpose of this basic qualitative design study was to illuminate on how teachers perceived their practice of guided reading in early grades when teaching reading comprehension. It also determined the advantages and disadvantages of implementing guided reading in early grades. The sample comprised of 15 early grade teachers chosen from different schools in the Northwestern suburbs of Chicago who had extensive experience teaching early grades using the guided reading approach. The major sources of data were semi-structured interviews and the teacher’s lesson plans of guided reading lessons. The collected data were analyzed through a coding process to identify themes while the lesson plans were subjected to a color-coding process. The findings exposed the teachers’ opinions about their experiences with the guided reading, its significance, how they implement it, reasons for using guided reading, and its impact on reading comprehension. It also reveals teachers’ beliefs about guided reading including its positive impact on student achievement and social growth and the perceived challenges that mainly included time constraints and challenges in planning and selecting materials for guided reading (GR) sessions. The research contributes to teaching practice by recommending the use of more effective and adequate training, professional development, and mentorship programs as interventions capable of assisting teachers to effectively implement GR.

Keywords: Guided Reading, Reading Comprehension, Zone of Proximal Development, Reading Skills.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Background of the Study

There is a difference between learning to read and reading to understand. In other words, “decoding competence does not automatically lead to better comprehension of a text” (Nayak & Sylva, 2013, p. 87). Likewise, Nayak and Sylva (2013) stated that “10–15% of the students’ exhibit low-level reading comprehension despite having good decoding skills” (p.88). In early grades, it is important that students not only learn how to read the text more effectively, but that they also develop a good understanding of what they are reading (Fisher, 2008). This would ensure that they gradually become strong readers with better reading comprehension. In doing so, students would gain proper knowledge of the text, be in a position to employ their knowledge effectively in various situations and ultimately be capable of solving various problems over time (Fisher, 2008; Fountas & Pinnell, 1996; Fountas & Pinnell, 2012, Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). Guided reading is highly recommended by most education scholars for facilitating students’ learning and comprehension (Fisher, 2008; Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Oostdam, Blok, & Boendermaker, 2015). Guided reading is often “implemented either as a constituent of classroom reading instruction or as a supplemental intervention” (Denton, Fletcher, Taylor, Barth, & Vaughn, 2014, p. 269).

Guided reading has become one of the most significant and common practices in primary classrooms in the United States (Fawson & Reutzel, 2000). Guided reading is a method of teaching reading widely used in English schools (Hanke, 2014). Dfee (1998) as quoted in Hanke (2014) “National Literacy Strategy (NLS) introduced Guided reading to English primary schools in 1999 as a part of a ‘carefully balanced programme’ for teaching reading” (p, 136). The key features of guided reading are as follow: small-group reading instruction to four to six students with similar strengths and instructional needs or to heterogeneously grouped students, these groups meet at least three to five times per week for 20 to 30 minutes each session in order for students to make consistent reading gains, multiple copies of graded leveled books are carefully selected and used by the teacher based on the children’s instructional need and levels of children’s reading development (Avalos, Plasencia, Chavez, & Rascón, 2007; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). This approach uses the context of personalized instructions and reading-related skills through extended time spent with an early grade student to ensure effective reading comprehension (Fountas & Pinnell, 2001; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). In implementing guided reading, teacher should act as a guide to build upon the knowledge, skills, and strategies the children already possess (Avalos e al., 2007; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). According to Miranda (2018), “ when teachers took the time to scaffold instruction, a guiding process, it led to increased reading performance” (p.2). Nevertheless, Iaquinta (2006), states that implementing guided reading instruction at the early stages of a person’s development is the good time since at this stage, it is easier to prevent reading problems. Student who is a poor in the first grade is 88% more likley to remian a poor reader in the forth grade (Iaqinta, 2006). According to research, students have a difficult time catching up when they start poorly in reading, and as a matter of fact, guided reading is one of the effective research-based strategies for keeping learners on track when it comes to reading (Iaqinta, 2006).

Even though guided reading is considered a significant approach to teaching learners the vital reading comprehension skills, teachers were even uncertain about what they were attempting to achieve with guided reading and how to achieve it (Marchard-Martella, Martella, & Lambert, 2015; Shang, 2015). Although numerous researchers provide evidence supporting the effectiveness of guided reading instruction and the benefits of student data (Burns, 2001; Burke & Hartzold, 2007; Burkins & Croft, 2010; Fountas & Pinnell, 1996; Kremer, 2013; Marchard-Martella et al., 2015; Massey, 2013; Saunder-Smith, 2009; Schulman, 2006; Shang, 2015), it is difficult to identify which strategies and skills contributed to improve student reading achievement. Researchers such as Belland et al. (2015) and Robertson (2013) concluded that guided reading was more effective when teachers reflected and adjusted their instruction to meet the reading needs of students, but the why to the decisions about which reading skill and strategy to use is unknown (Miranda, 2018, p. 6). Research also indicated that teachers need to have a better understanding of the use of skills and strategies to enhance comprehension and to meet the reading needs of students (Buckingham, Beaman, & Wheldall, 2014; Fuchs, Fuchs, & Vaughn, 2014; Johnson & Boyd, 2012; Leu & Maykel, 2016; Miranda, 2018; Muszynski & Jakubowski, 2015; Shang, 2015).

Problem Statement and Significance of the Study

Guided reading is generally believed to be difficult to implement within English speaking elementary schools as Hanke (2014) noted that teachers in primary school have continuing concerns about its interpretation and implementation. In fact, some teachers were even uncertain about what they were attempting to achieve with guided reading, let alone how they should go about achieving it (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017; Hanke, 2014; Marchard-Martella et al., 2015; Shang, 2015).

A review of recent literature shows a general shift within US schools with the aim of including guided reading as a crucial instructional approach for attaining quality literacy. While the practice has been used for several decades with success in primary school, several studies have explored guided reading within the early education context and discovered multiple concerns on the interpretation of the instructional approach (Fisher, 2008; Ford & Opitz, 2011; Hanke, 2014). Despite the extended research on guided reading as an instructional strategy, there is still a need for research that thoroughly investigates in-depth teachers’ perspectives on the implementation of guided reading, particularly pertaining to its influence on reading comprehension (Fisher, 2008; Ford & Opitz, 2011; Hanke, 2014). Based on the existing literature, few studies have examined the effects of implementing guided reading on reading comprehension using qualitative research designs, leaving this subject vulnerable to misinterpretation and partial implementation (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012).

In an attempt to address this gap, this study focused on the teachers’ perspectives on the implementation of guided reading in early grades and its effects on reading comprehension. Using a sample composed of 15 teachers selected from public schools located in the northwest suburb of Chicago, this study had two goals: 1) to explore how teachers describe their practices of guided reading in early grades when teaching reading comprehension, and 2) to determine the advantages and disadvantages of implementing guided reading in early grades.

Theoretical Framework

The guided reading strategy is aligned to Vygotsky’s (1978) perception of learning through the creation of an effective and meaningful social instruction setting (Young, 2018). Vygotsky (1978) stressed that guided reading is deeply rooted in social constructivism whereby the learners learn through interactions with other students and the teacher. The social aspect is hence a crucial tenet for guided reading sessions. Fisher (2008) echoed this in the claim that under the social-constructivist outlook, students in guided reading are often “encouraged to talk, think, and read their way to constructing meaning” (p. 20).

Consequently, the theoretical framework of this study is Vygotsky’s social constructivism, particularly the notion of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). According to Vygotsky (1978) ZPD is “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86). Teaching and learning processes are, therefore, perceived to be constructive and active process that occur within social contexts, which particular extents characterize the guided reading approach as well. The social constructivism theoretical framework will assist in designing this basic qualitative inquiry and ensuring that the interview questions will be semi-structured so that the researcher can listen keenly to the experiences shared by the participants (Creswell, 2013). The theoretical framework will be discussed in details in the second chapter.

Researcher’s Positionality

According to Cormier (2018), “Most of the literature on insider/outsider researcher positionality deals with ethnicity and race, yet language is also an important position to explore” (p. 330). The characteristics that make up the researcher, specifically the language spoken (whether linguistic outsider or insider), can profoundly shape the nature of the data gathered. Other than affecting the dependability and the accuracy of the data, it can also determine the nature of the association established between the researcher and the participating individuals. Apart from language, of course, other factors that shape the quality of the data gathered include the researcher’s experience, interests, passions, perceptions, and values. Considering the amount of influence such factors can have on the data collected, it is necessary to disclose any such influence or connection to the potential reader given that they can either benefit the research or even harm it.

Cormier (2018) states, “outsider researchers are often defined as ‘neutral’ and ‘objective.’ As such, participants may feel more comfortable talking about political issues or sensitive topics with outsiders who are not involved in the same way as an insider researcher” (p. 330). At the time of conducting the study, there was exist no working relationship between myself and the participants, hence ensuring the collection of more credible data. However, the participating teachers were of different native language (English) from mine (Arabic). The language difference had improved the interview process; the participants gave more detailed responses and offer clarifications, considering that I am not a native speaker. Additionally, it was easier for me to ensure anonymity given that no previous relationship exists between the participants and me, hence making them more open to sharing their opinions.

Purpose of the Study

This study was to explore teachers’ perspectives on the implementation of guided reading in early grades and its effects on reading comprehension. The purpose of this study was to: 1) explore how teachers describe their practices of guided reading in early grades when teaching reading comprehension, and 2) determine the advantages and disadvantages of implementing guided reading in early grades. The outcome of the study provided a greater understanding of the implementation of guided reading which, in turn, affect my decision on using this particular strategy when I will be back home to my country.

Research Questions

This qualitative study was guided by the following questions:

R1: How do elementary school teachers describe their experiences with guided reading strategies?

R2: What are teachers’ perspectives of the impact of guided reading on reading comprehension in early grades?

R3: How do teachers describe advantages and disadvantages of utilizing guided reading in early grades?

Rationale for Methodology

This research followed a basic qualitative study (BQS) approach. Generally, basic qualitative studies are interested in the way in which meaning is constructed as well as how persons make sense of their lives and that of their surrounding (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Thus, the fact that the researcher will have to attentively listen to the participants’ words with the aim of capturing their view and experiences about the implementation of guided reading makes basic qualitative study methodology appropriate for this study.

15 teachers from public schools were selected to explore their perspective of implementing guided reading in early grades on reading comprehension. Semi-structured interviews and artifacts in the form of teachers’ lesson plans, were considered as data sources in this study. These data were analyzed thematically using an inductive analysis method.

Definition of Terms

For this study, the following definitions applied:

Reading: Reading is unlike the major assumption that reading simply means isolating words in a text, reading is more of a productive process where the reader creates meaning, the ultimate goal being comprehension, hence a more complex process that involves phonemic awareness, identifying words, being fluent, mastering the use of vocabulary, and understanding the reading material (Tompkins, 2010, p. 42).

Balanced Literacy: Based on a view of scaffolded instruction or gradual release of responsibility where teachers provide varying levels of support based on children’s needs, balanced literacy instructional practices are often enacted through the use of specific instructional routines such as guided reading, shared reading, interactive writing, literacy centers and independent reading and writing. (Bingham & Hall-Kenyon, 2013)

Guided Reading: A small-group instructional context in which a teacher supports each reader’s development of system of strategic actions for processing new texts at increasingly challenging levels of difficulty. Students in the group are similar (although not exactly the same) in their development of a reading process, so it is appropriate, efficient, and productive for them to read the same impact … The ultimate goal of instruction is to enable readers to work their way through a text independently, so all teaching is directed toward helping the individuals within the group build systems of strategic actions that they initiate and control for themselves. Guided reading leads to the independent reading that builds the process; it is the heart of an effective literacy program. (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017, pp. 12-13)

Reading Comprehension: A process of making meaning from texts. It implies that readers do not make meaning from the printed words which are set directly in essays or paragraphs, but they build meaning from pieces of information, from whole sentences that are correlated to each other in those essays. (Muliawati, 2017, p. 94)

Zone of Proximal Development: The zone of proximal development refers to that with the backing of another person with better capabilities, the learner has an increased chance of doing better than they could individually (Vygotsky, 1978).

Summary and Organization of the Remainder of the Study

This chapter addressed a brief discussion of implementing guided reading in early grades. Through well-organized guided reading sessions, such students have a better opportunity for learning how to read effectively as well as putting the knowledge gained into use in various situations, thus having the ability to solve real-world problems (Fisher, 2008). This is considering that effective reading involves both the ability to decode information as well as to comprehend whatever is being read. Based on the Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, guided reading assumes that learners are born different in both background and abilities, hence the need to form small groups in classrooms where the learners showing similar reading behaviors and with same instructional needs are exposed to reading at about the same book level with active involvement and support of their teacher (Fountas & Pinnell, 2001; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017).

Nonetheless, because teachers have various perspectives on the implementation of guided reading in early grades on reading comprehension, which forms the major purpose of this research, a basic qualitative research design was suffice in answering the study’s research questions. Through semi-structured interview questions, the research brought into perspective the teachers’ describing of the impact of implementing guided reading in early grades on reading comprehension, the advantages/disadvantages of guided reading in early grades, and how teachers describe their practices of guided reading strategies. The justification for the use of basic qualitative approach was because the study was primarily interested in the discovering the manner in which meaning is constructed by the participants (Merriam, 2009).

The second chapter of the study focuses on the current literature relevant to this study. The third chapter presents the methodology as well as the procedures that will be utilized in the inquiry.

Chapter Two: Literature Review

Introduction to the Chapter

This study aimed at exploring teachers’ perspectives of the impact of implementing guided reading on reading comprehension among early graders. This study, therefore, explored how teachers describe their practices of guided reading in early grades when teaching reading comprehension, and determine the advantages and disadvantages of implementing guided reading in early grades. Using a number of peer-reviewed articles and scholarly books, this chapter has reviewed existing literature to offer a comprehensive analysis of the guided reading strategy of learning and teaching, in accordance to the study’s theoretical framework.

First, the analysis entailed an overview of the theoretical framework followed by a discussion of teachers’ knowledge of comprehension instruction and its implementation. Second, it examined the literature on guided reading and reading comprehension. Third, the analysis entailed a historical context of guided reading including a discussion of the origin of guided reading, its definition, modern scope, and teacher’s knowledge of guided reading. Fourth, it included a detailed understanding of the guided reading approach, the structure of a guided reading lesson, and the grouping in guided reading sessions. Fifth, it looked at some of the significant underpinning theories. Finally, it addressed literature on the teachers’ perspectives on the use of guided reading.

Theoretical Framework

In reference to the theory of guided reading, Young (2018) stated that:

In theory, it seems that guided reading should work. Most prominently, it has roots in social constructivism. Firstly, students are able to learn by interacting with the teacher and their peers. Thus, the social aspect is obvious in this context. Furthermore, the framework certainly resembles social constructivist learning theory. (p. 1)

Accordingly, the theoretical framework of the proposed study is social constructivism of Lev Vygotsky, particularly Vygotsky’s notion of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). In fact, Vygotsky (1978) defined ZPD as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86). Learning is thus perceived as a constructive and active process occurring in social contexts, which to a considerable extent characterizes the guided reading approach as well. In guided reading, the teacher offers varying levels of support during the instructional activities, all aimed at scaffolding the control of each learner (Gaffner, Johnson, Torres-Elias, & Dryden, 2014; Marchard-Martella et al., 2015). Consequently, the amalgamation of events enables a gradual move within the student’s zone of proximal development (ZPD), “what the individual learners can do with the involvement of the teacher, to full and independent control” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). In guided reading instruction, the teacher usually organizes the teaching or learning collaboration thoughtfully while considering the make-up of the small groups as well as text selection.

Social constructivism has greatly influenced past research that primarily focused on literacy and language learning and teaching (Powell & Kalina, 2009). Besides, social constructivism has also contributed immensely to the underpinnings of the guided reading as it illuminates the significance of social context and its effect on the learning process. Moreover, the notion of reading comprehension to be explored in this research often encompasses and is influenced by social constructivism, whereby the students interact, think, share their perception, read to construct meaning, and respond to the text with reference to their real life experiences (Fisher, 2008).

The proposed research will utilize a basic qualitative methodology as the researcher is interested more in the actual outer-world content of her questions (the actual opinions themselves, the participants’ reflections themselves) and less on the inner organization and structure of the participants’ experiencing processes (Percy, Kostere & Kostere, 2015). Consequently, the research will be approached through a social constructivism lens in general and through the ZPD in particular. According to Mensah, (2015), social constructivism “provides a frame that shifts emphasis from the individual construction of knowledge to a view of collectively constructed meaning” (p. 3). In accordance with Creswell (2013), people construct subjective meanings and interpretations of their experiences in the effort to understand their world. Such subjective meanings are often mediated historically and socially. Utilizing this theoretical framework, therefore, will heavily rely on the interaction processes of the teacher participants. In obtaining an in-depth understanding of the teachers’ subjective experiences in the implementation of the guided reading approach, the social constructivism will be effective in creating close relations with the teacher participants. The aim of this research will be to understand how elementary school teachers make sense of their teaching experiences using the guided reading approach.

The current research will rely on the early grade teachers’ views on the effects of guided reading on reading comprehension. Accordingly, the questions for the semi-structured interviews will be general and broad to enable the participants to construct meanings of various situations attained through their interactions when implementing guided reading. Generally, social constructivism will assist in designing the basic qualitative inquiry, ensuring that the questions will be more open-ended so that the researcher can listen keenly for what the participants do and say about their experiences (Creswell, 2013).

Teachers’ Knowledge of Comprehension Instruction and its Implementation

Reading comprehension is essential in learning, understanding, and knowing language as a medium of communication. It is the motive behind reading whereby effective reading only occurs when the reader is able to understand the text rather than only decoding the words (Bria, 2018; Kuşdemir & Bulut, 2018). Reading comprehension can be defined as the process by which meaning is constructed from texts. Therefore, rather than constructing meaning from printed words found directly in paragraphs and essays, meaning is constructed from pieces of information gathered from and scattered across correlating whole sentences within the essay or text (Muliawati, 2017). Effective reading comprehension requires the reader to have cognitive skills. Reading comprehension also requires the reader to rely on prior knowledge on the subject covered in the text, prior experience as listeners and readers, using their vocabulary, knowledge of syntax, the text structure, and cognitive strategies to make sense of the text being read.

Additionally, various skills are required of the reader for him/her to accurately comprehend texts. These skills include having a purpose for reading and being active during reading; ability to analyze text while making predictions prior to the actual reading; eliciting meanings of the words used in the text and the context in which they are used; leveraging in previous knowledge; ability to reconstruct meaning; ability to summarize both events and characters in fictional texts (Bulut, 2017). According to Bulut (2017), reading comprehension is, therefore, a complicated process that necessitates a combination of the reader’s previous knowledge and vocabulary, interacting with the text, and the ability to use reading comprehension strategies.

Various literature provide different classifications and titles for comprehension strategies. On major classification of comprehension strategies was suggested by Taraban, Kerr, and Rynearson (2004) who classified comprehension strategies into pragmatic and analytical reading strategies. Taraban et al., (2004) defined analytical reading strategies as those that necessitate the reader to evaluate, contemplate on how they can later utilize what they acquire from the text, deduce meanings from titles by relating to the content in the text, and making inferences. It also requires the readers to review, make inferences, make guesses and check whether such guesses are correct, visualize the text, identify relevant information, and identify the text’s difficulty level (Taraban et al, 2004). On the other hand, pragmatic reading strategies are those that assist readers in remembering what they read through the use of various actions that include highlighting major points, note taking, re-reading, and using the margin to take notes (Asikcan, Pilten, & Kuralbayeva 2018; Taraban et al, 2004).

Another major classification of reading comprehension strategies makes use of the order in which the strategies are utilized during reading processes. These include pre-reading strategies; during/while-reading strategies, post-reading strategies, and strategies used throughout the entire reading process (Asikcan et al., 2018; Bulut, 2017). Pre-reading strategies include the preparation of reading plans, making predictions based on the main title, sub-titles, and visual presentations, determination of the reading speed, activation of prior knowledge, creation of pre-teaching vocabulary, selecting texts and guiding students to selects texts according to the stipulated criteria, and constructing word pools (Asikcan et al., 2018; Bulut, 2017).

During/while-reading strategies focus on the objectives of the pre-reading strategies (Asikcan et al., 2018; Bulut, 2017). During reading strategies include absorbing and fluent reading, utilizing study guides and drafts for informative texts, use of flow diagrams and timelines, note taking, visualizing narrative texts, definition of vocabulary, answering and creating new questions, connecting information obtained from different paragraph, and utilizing textual clues (Asikcan et al., 2018; Bulut, 2017).

Post-reading strategies on the other hand are aimed at synthesizing and strengthening knowledge obtained during the pre-reading and during-reading strategies (Asikcan et al., 2018; Bulut, 2017). Common post reading strategies include summarizing texts, answering questions, relating answers from different questions, analyzing and evaluating new information, reflective thinking, identifying the major idea of the text, discussion with peers, and checking for the validity of predictions made during pre-reading process (Asikcan et al., 2018; Bulut, 2017).

In addition to the above strategies are general strategies used throughout the reading process for different purposes. These include strategic note-taking, “the SQ4R (survey, question, read, recite, relate, review), SQ3R (survey, question, read, recite, review), KWL (Know, want to know, learned), POSSE (predicting, organizing, searching, summarizing, and evaluating), DRA (directed reading activity), and Coop-DIS-Q (Cooperative discussion and questioning)” (Bulut, 2017, p. 24).

Numerous studies indicate that readers who have challenges in reading and comprehension can be guided to overcome such challenges more effectively if they are taught the afore-discussed comprehension strategies explicitly. (Antoniu & Souvignier, 2007; Asikcan et al., 2018; Bulut, 2017; Eilers & Pinkley, 2006; Scarlach, 2008). Comprehension is thus important for readers to deepen and expand their understanding of a text and enable them to react critically to a text. Comprehension is the reason behind reading with an aim of attaining meaning from a particular text.

Despite the abundance of research-based evidence supporting instruction using reading comprehension approaches, studies conducted in the U.S.A, Ireland, and Australia (Concannon-Gibney & Murphy, 2011; Ness, 2009; Pilonieta, 2010; Platterson et al., 2018) have indicated that most teachers do not implement reading comprehension instruction while teaching. For instance, Ness (2009) reported that in his study examining the level to which teachers implement reading comprehension instruction in adolescent classrooms, none of the high school learners’ study time was dedicated to reading comprehension instruction (Ness, 2009). Haager and Vaugn (2013) maintain that irrespective of the certainty assured through research that comprehension is an essential element of reading instruction, past studies indicate the absence of comprehension instruction within classrooms (Klingner, Urbach, Golos, Brownell, & Menon, 2010). There exist numerous evidence-based comprehension instruction strategies (Boardman et al., 2016; Dexter & Hughes, 2011), nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly difficult to implement such effective practices to classrooms (Landrum, Cook, Tankersley, & Fitzgerald, 2007; Platterson et al., 2018).

A major reason cited by most teachers for not implementing reading comprehension instruction in their classrooms is the lack of training in comprehension instruction (Mehigan, 2005; Ness, 2016; Platterson et al., 2018). In Ness’ (2016) study aimed at examining the frequency at which reading comprehension was used in both middle and high school science and social studies classroom contexts, teacher participants claimed they lacked training and professional knowledge in reading comprehension instruction, which acted as the major barrier to their implementation of this instructional approach. Consequently, some teachers felt unqualified and never comfortable implementing reading comprehension instruction claiming they had not received such training (Ness, 2016).

Another reason as to why comprehension instruction is unpopular in classrooms, especially elementary classrooms is the teachers’ lack of understanding and knowledge in the active elements of reading that form the basis of reading comprehension (Ness, 2011; Platterson et al., 2018; Pressley, 2006). Additionally, most teachers lack the knowledge and skills needed to teach comprehension strategies as these strategies are often complicated, especially as they entail challenges in delicately balancing the appropriate comprehension strategy and the text’s content and challenges in identifying ideal texts (Block & Lacina, 2009). The mental modeling necessary for the effectiveness of comprehension instruction could also be challenging for most teachers considering that it takes an average of one year for a teacher to be proficient in implementing comprehension instruction (Pressley & El-Dinary, 1997, Ness; 2011).

Despite the issues that teachers claim to have related to the implementation of comprehension instruction, a review of past research indicates that most of these issues are not mainly based on the teacher’s knowledge or their perceptions and attitudes but rather on their confidence on their ability to implement comprehension instruction continuously (Silver & Png, 2015). Landrum et al., (2007) suggested that teachers fail to use research based instructional approaches such as comprehension instruction as they are not presented in a manner that they can be readily applied. In addition, Platterson et al. (2018) proposed that teachers are likely to adopt and respond more positively to descriptions by other teachers on instructional approaches that have worked in their classrooms. Consequently, Landrum et al., (2007) suggested that most teacher pre-service preparation services equip most teachers with the knowledge of different comprehension instructional approaches, however, testimonies of the effectiveness of such a teaching approach could foster implicit endorsement of implementation and usability when such sentiments come from fellow teachers. Consequently, adequate and effective training and professional development in a narrow number of content-specific comprehension instructional strategies rather than a wide-variety of strategies integrated to research based testimonials from fellow teachers could assist in improving the knowledge base and the resultant implementation and uptake of such an approach (Kissau & Hiller, 2013; Landrum et al., 2007; Nurie, 2017).

Since the above research findings indicate that teachers are either unaware or not confident in teaching comprehension, the next sections explore guided reading as an approach to teaching comprehension and its effect on reading comprehension in early grades.

Guided Reading and Reading Comprehension

Nayak and Sylva (2013) argued that about 10 to 15 percent of learners show low-level reading comprehension abilities despite being ranked highly in decoding skills. According to Muliawati (2017), reading comprehension is:

A process of making meaning from texts. It implies that readers do not make meaning from the printed words which are set directly in essays or paragraphs, but they build meaning from pieces of information, from whole sentences that are correlated to each other in those essays. (p. 94)

Over the recent past, there has been a growing interest in research on reading comprehension, especially in Canada and the USA (Nayak & Sylva, 2013). This has necessitated research on instructional strategies and materials capable of nurturing reading comprehension to address the needs of students facing reading challenges. (Nayak & Sylva, 2013).

However, according to Denton et al. (2014), there is limited experimental research that examines instructional interventions and strategies that implement the guided reading strategy. Moreover, only a few studies have explored the impact of guided reading on reading comprehension (Denton et al., 2014; Ferguson & Wilson, 2009; Nayak & Sylva, 2013; Scull, 2010; Tobin & Calhoon, 2009). Their findings have indicated mixed conclusions and concerns over the impact of guided reading on reading comprehension.

Nayak and Sylva (2013) experimentally assessed the guided reading strategy as a supplementary English reading strategy for ESLs in Hong Kong against reading a similar text from e-books without teacher-led guidance. Their findings, though suggestive rather than conclusive, indicated that students in the guided reading setting outperformed their counterparts in reading comprehension and accuracy. This was despite the fact that there were no major differences between the two interventions. The findings suggested a need for teacher guidance on interaction and comprehension strategies to assist in negotiating the meaning in groups.

Ferguson and Wilson (2009) also reported that teachers across four Texas schools who reported using guided reading in the classroom had students with greater reading comprehension and fluency. In fact, teachers noted that students who were exposed to guided reading would often independently draw upon the guided reading strategies to improve their reading comprehension and fluency (Ferguson & Wilson, 2009). Similar results were also discovered in a comparative study that was done by Whitehead and de Jonge’s (2013-14). Their findings indicated that guided reading fostered the students’ engagement levels and their comprehension of science texts. Scull’s (2010) report showed that modeling reading strategies, guidance fostered by thoughtful motivation, careful questioning, and the introduction of clear and ideal comprehension and processing strategies supported young students in processing and comprehending text at higher levels. Scull’s findings were significant as these teaching strategies are the most utilized by teachers of guided reading.

On the other hand, Tobin and Calhoon’s (2009) comparison of the impact of the guided reading strategy against an extremely explicit intervention that offered direct instruction in comprehension and phonics strategies reported trivial differences in their effects on the students’ reading and learning outcomes. Denton et al. (2014), though supporting guided reading suggested that using a more explicit instructional strategy has a greater impact on the students’ text reading comprehension, fluency, and phonemic decoding. The authors emphasized that students encountering learning challenges could develop a greater reading comprehension from a more structured, explicit, and sequential instructional approach. Another study by Savage, Abrami, Hipps, and Deault (2009) compared the impacts of a balanced literacy approach that used guided reading against two computerized phonics-oriented reading strategies. Their findings indicated that the computerized strategy had significantly better and superior outcomes on listening comprehension, reading comprehension, phonemic awareness, and reading fluency compared to the balanced literacy approach that used guided reading. Fisher (2008) also observed a similar scenario in the small-scale research where she reported the absence of evaluative comprehension and the lack of the transfer of inferential comprehension skills to the students in the sessions that she observed.

There are several studies which have revealed that reading comprehension required teacher scaffolding strategies to improve the students’ problem-solving skills, ability of inquiry, and efficacy (Fisher, 2008; Denton et al., 2014; Ferguson & Wilson, 2009). Based on this literature review, it is evident that few studies have examined the effects of implementing guided reading on reading comprehension using experimental or quasi-experimental research designs. Moreover, there are even fewer studies which have directly studied the effect of guided reading on reading comprehension for early graders from the teachers’ perspective.

The Historical Context of Guided Reading

Though the works of several scholars such as Tierney and Readence (2000) and Tyner (2004) have linked the foundation of guided reading to Fountas and Pinnell (1996), guided reading, as an educational concept is not as recent as many may think (Piercey, 2009). Historically, guided reading has its origins in New Zealand schools whereby its use in giving guidance and direction to students, particularly by nurturing reading, has been utilized since the 1940s after the establishment of Bett’s (1946), “Directed Reading Activity” (Ford & Opitz, 2011, p. 226). As highlighted by Ford and Optiz (2011), the term ‘guided reading’ based on Betts’s concept of teacher-directed teaching, was later on used by educators such as Dora Reese and Lilian Gray in their teaching practice for lessons and classes designed to facilitate young student’s reading development. From this, several other subsequent scholars such as Manzo (1975) would contribute to the idea of guided reading (Piercey, 2009).

Manzo (1975) stated that guided reading procedure is designed to “improve reading comprehension by stressing attitudinal factors- accuracy in comprehension, self-correction, and awareness of implicit questions, as well as cognitive factors, unaided recall and organizational skills” (p. 291). According to Piercey (2009), “in 1975, Manzo described a ‘guided reading procedure’ that, despite its rigid structure, bears some similarities to the current model of guided reading described by Fountas and Pinnell” (p. 7).

Before the work of Fountas and Pinnell (1996), Mooney (1990) had also addressed the concept of guided reading in her book Reading to, with, and Children. Later on, after the publication of Guided Reading: Good first Teaching for All Children (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996), “guided reading has become a common term used among educators in Canada and the United States” (Piercey, 2009, p. 7). Fountas and Pinnell (1996) contributed to the field of guided reading by arguing this approach is at the heart of a balanced literacy program.

Despite the inadequate number of studies focusing solely on guided reading, most recent studies seem to agree on the definition of the approach as an element of a balanced literacy intervention (Ford & Optiz, 2008). Fountas and Pinnell (2017) provided one standard definition for the guided reading strategy from 1996 until 2017 as:

A small-group instructional context in which a teacher supports each reader’s development of system of strategic actions for processing new texts at increasingly challenging levels of difficulty. Students in the group are similar (although not exactly the same) in their development of a reading process, so it is appropriate, efficient, and productive for them to read the same impact. The ultimate goal of instruction is to enable readers to work their way through a text independently, so all teaching is directed toward helping the individuals within the group build systems of strategic actions that they initiate and control for themselves. Guided reading leads to the independent reading that builds the process; it is the heart of an effective literacy program. (pp. 12-13)

Mooney (1990) also defined guided reading as an instructional approach implemented in classrooms to help the students become “independent readers who question, consider alternatives, and make informed decisions as they seek the meaning” (p. 47).

The main goal of guided reading is to enable the students to synthesize and process texts by becoming effective and efficient independent silent readers (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012). As a literacy program in the classroom context, research on guided reading emphasizes the significant role it plays as an integral part of balanced and quality literacy intervention (Ford & Optiz, 2011; Fountas & Pinnell, 2012). To enable the students to develop into strategic readers, teachers have the role of guiding them to nurture reading behaviors. This can only happen if the educators themselves acknowledge and are aware of the efficient reading behaviors to assist in identifying the required amount of support (Denton et al., 2014; Hulan, 2010). According to Denton et al. (2014), teachers are often guided by explicit objectives aimed at offering direct justifications and modeling various skills, concepts, while creating chances for both independent and guided practice to prompt overt educative and progressive feedback. This is reiterated by Ford and Optiz (2008), who asserted that the success of the guided reading approach, particularly in the achievement of the desired outcomes, is dependent on the teacher’s know-how on the needed elements and its implementation.

The teachers identify and utilize the needs of the struggling readers with an aim of designing instructional practices capable of attaining accelerated and intensive instruction, numerous reading opportunities, and promoting authentic discussions based on the reading (Allington, 2013; Hulan, 2010; Peterson & Taylor, 2012). Guided reading groups are an essential part of guided reading sessions whereby the teacher is expected to thoughtfully construct groups and introduce a leveled book to the students who, in turn, are required to read simultaneously and independently with the teacher acting as the coach and following up with specific interruptive discussions (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012). In accordance with (Ford & Optiz, 2008), these student groupings ought to be flexible and fluid in nature and as backed by Morgan et al. (2013), founded on the needs of the individual students with respect to their specific reading abilities and experiences. The students are then expected to read at almost the same level while using a common and leveled text, but guided by an effective instruction to support them in reading texts that could be on the edge of their reading and learning abilities (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012). The implementation and design of guided reading groups based on the students’ needs and continuous reliable assessment data enables the teachers to effectively and efficiently address the dynamic needs and varying learning paths of the students (Ford & Optiz, 2008; Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Morgan et al., 2013).

Teacher’s Knowledge of Guided Reading

Effective implementation of the guided reading approach necessitates comprehensive knowledge of this instructional approach, the choice of quality and appropriate tests, the process of reading development, and the reading process, which often demands time, professional development, and/or support from a coach (Fountas & Pinnel, 2012; Fountas & Pinnel, 2017). Additionally, past studies exploring the perceptions of teachers on the elements of guided reading indicated that most teachers perceived some elements of the approach to be more difficult demanding more time for them to attain skills and knowledge needed to implement the guided reading approach effectively (Fountas & Pinnel, 2012; Fountas & Pinnel, 2017). Research indicates that the process of selecting the ideal text is perceived to be the least challenging whereas targeted teaching to address the immediate needs of the learners and the process of establishing quality discussions and interactions about the text after independent reading was perceived to be the most challenging features of the guided reading approach by most teacher participants (Fountas & Pinnel, 2012; Fountas & Pinnel, 2017).

Such findings could have severe implications for educators and curriculum and instruction leaders considering that other studies report a relation between teachers’ knowledge of the guided reading approach and the degree to which guided reading impacts the students’ reading development. Past research has also reported that the lack of articulate and sufficient knowledge on the implementation of the guided reading approach often makes teachers to lack confidence and feel uncertain with respect to the implementation of the approach in their classrooms. Such low levels of confidence and insufficient knowledge adversely affect the effective implementation of the guided reading approach. For instance, the research by Ferguson and Wilson (2009) examining the guided reading approach in schools in Texas reported a distinct relation between teachers’ knowledge of the guided reading strategy, teachers’ confidence level, and the degree of impact that the approach had on the students’ reading development. Teachers who had prior training in the approach portrayed sound knowledge of the approach supported by an effective implementation of guided reading with much confidence (Ferguson & Wilson, 2009). These teacher participants were also found to be more willing to support the students’ reading development in comparison to teacher participants who had little knowledge and confidence in the guided reading approach (Ferguson & Wilson, 2009). The research findings also indicated that the benefits of the guided reading approach were only cited by the teacher participants who had sufficient knowledge in the approach and thus were able to implement it effectively (Ferguson & Wilson, 2009). Consequently, Ferguson & Wilson concluded that “if we want teachers to implement guided reading in ways conducive to the growth of student reading capabilities, they need a deeper understanding of what guided reading means as well as the procedural framework involved” (p. 303). Teachers’, therefore, should be coached and mentored in the approach and offered administrative support until they are confident in its implementation (Ferguson & Wilson, 2009).

Kruizinga and Nathanson (2010) also made similar conclusions informed by a study that examined the implementation of the guided reading approach in three primary schools in Cape Town, South Africa by teachers of grade one and grade two classes. Kruizinga and Nathanson claimed found out that the participants were struggling with the implementation of the approach mainly due to the absence of detailed and explicit guideline in the country’s literacy policy on guided reading and its implementation, the absence of professional development initiatives to assist teachers in developing an understanding and knowledge of the guided reading approach, and insufficient quality guided reading resources including leveled texts (Kruizinga & Nathanson, 2010). Based on their research findings, the researchers suggested that the absence of practical and systemic support for the teachers such as via training, providing high-quality of guided reading resources, and professional development, made the effective implementation of the guide reading approach in South African classes very challenging.

Though the findings by Kruizinga and Nathanson (2010) ought to be deliberated tentatively due to the small-scale nature of their study, their conclusions are consistent with those of Fountas and Pinnell (2012) on the need for in-depth and expert knowledge and skills to facilitate the success of the approach. Hanke (2013) also shared similar conclusions by arguing that the little studies examining the implementation of guided reading since it was introduced in the United Kingdom education setting in 1999, proposes the existence of insufficient and clear guidelines that adversely affects the teachers’ understanding of the guided reading approach. Hanke (2013) suggested that the absence of sufficient and clear guidance results to the prevalence of challenges in the interpretation of the policies surrounding the guided reading approach and its implementation.

Another research by Wall (2014) emphasized the value of the guided reading approach but also argued that the approach could transform into a learning setting whereby teachers predominantly focus on independent reading, a situation that limits the learners from having sufficient time to read continuous text. This poses a potential risk as teachers could become complacent and fail to completely address the needs of their students in guided reading sessions as they tend to emphasize similar skills with different student groups (Wall, 2014). Such a classroom situation and practice could be caused by the absence of clarity and sufficient knowledge on the guided reading approach, highlighting the need for in-depth knowledge and training of teachers in the guided reading approach to facilitate its effective uptake and implementation. The next paragraphs will explain in details the structure of a guided reading lesson.

Structure of a Guided Reading Lesson

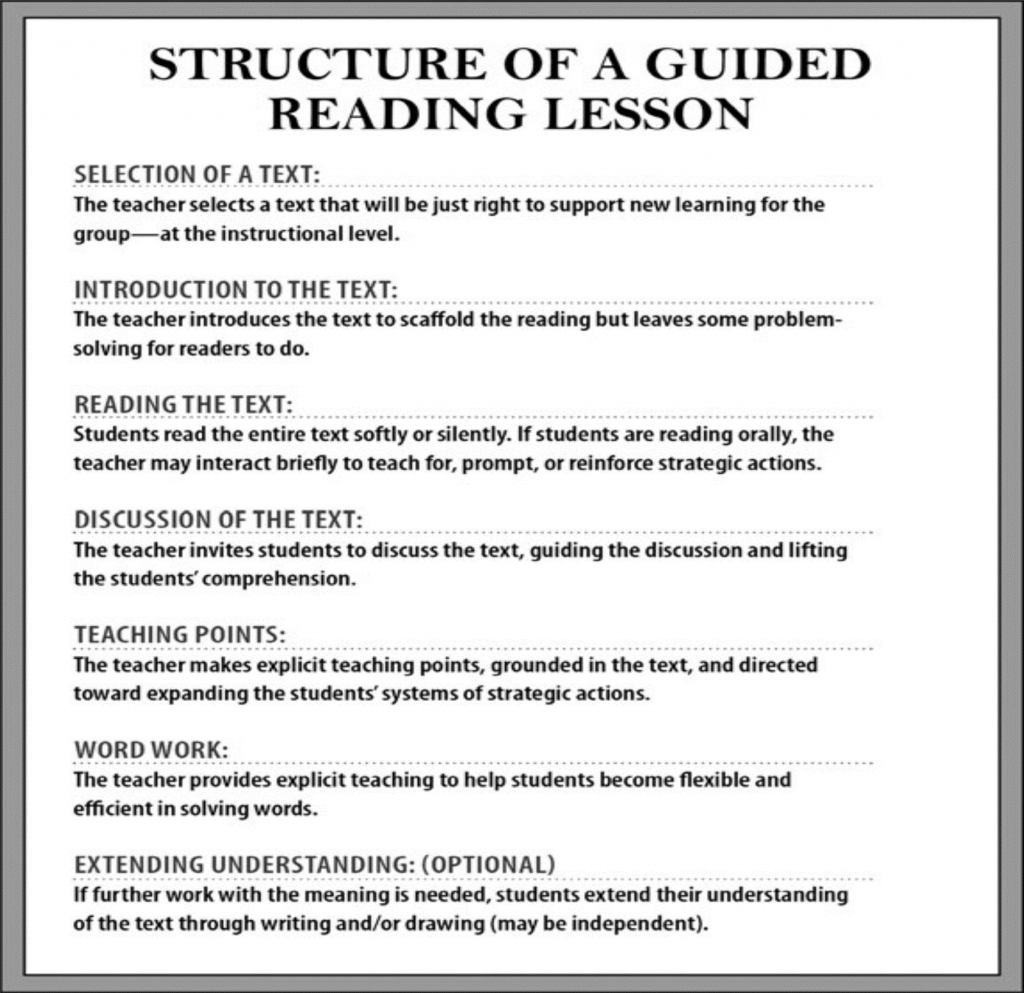

The following components are the structure of a guided reading lesson: selection of text, introduction to the text, reading the text, discussion of the text, teaching points, word work, and extending understanding (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996; Fountas & Pinnell, 2010; Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). These components work together to “form a unified whole and create a solid base from which to build comprehension” (Iaquinta, 2006, p. 417). The following figure 1 explains these structures.

Figure 1. Fountas and Pinnell Structure of Guided Reading Lesson. Fountas and Pinnell (2011).

Selection of a text or selection of leveled books. In preparation for a guided reading lesson, the teachers first identify the purpose and focus of the session dependent on the common needs of the target students (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). The next element revolves around the identification and selection of a leveled text, which should be matched to the student’s reading ability and, which comprises of slightly challenging text features with an aim of exposing the learners to texts and structure they would rather not choose if given the choice (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017; Hanke, 2014). Lipp and Helfrich (2016) stress that text comprising of slightly challenging features enables the students to read most of it independently while expecting to meet occasional challenges for which the teacher ought to offer the appropriate support. This also creates an opportunity for the students to apply their developed reading processing techniques to the new texts, read it independently and successfully, and overcome any challenges with the appropriate support from the teacher (Lipp & Helfrich, 2016). In addition to offering more challenging and sophisticated features, “the text selected should also be an unknown text to give the readers the opportunity to apply familiar reading processing strategies to unfamiliar texts” (Ciuffetelli, 2018, p.5)

Fountas and Pinnell (2012) stated that:

One of the most important changes related to guided reading is in the type of books used and the way they are used. Teachers have learned to collect short texts at the levels they need and to use the levels as a guide for putting the right book in the hands of students. The term level has become a household word; teachers use the gradient of texts to organize collections of books for instruction. (pp. 269-270)

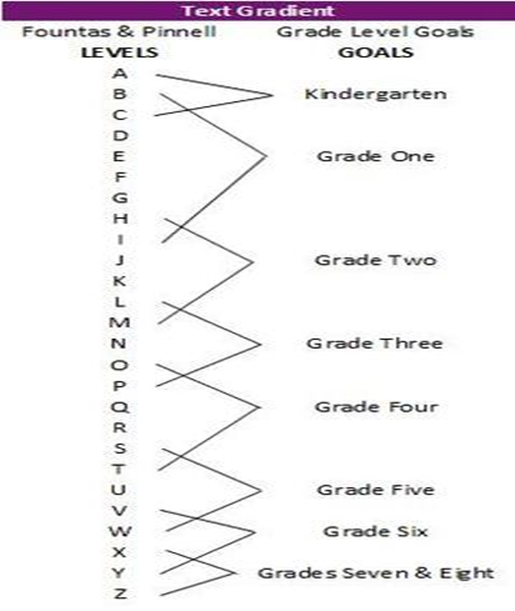

According to Lyons and Thompson (2011), leveled book refers to “reading materials that are ordered from simpler to more complex tasks according to a specific set of criteria” (p. 159). Criteria used by Fountas and Pinnell (2001) include: book and print features (e.g., length, layout, graphic features), vocabulary, sentence complexity, content, text structure (e.g., fiction/nonfiction), language and literacy features (e.g., literary/figurative language, dialogue),

and themes and ideas. Figure 2 is the text gradient according to Fountas and Pinnell (2011):

Figure 2. Fountas and Pinnell Text Gradient Levels. Fountas and Pinnell (2012).

Introduction to the text. In this component, the teacher introduces the text by prompting a discussion on the new text emphasizing on the intended purpose and arousing the learner’s interest in the reading by trying to reflect on previously encountered concepts and knowledge gathered in previous readings and trying to connect them to the current text (Scull, 2010; Morgan et al., 2013). Such discussions enable the teacher to activate and build on previous knowledge and model effective prediction and link approaches that the learners can adopt and use independently (Scull, 2010; Lyons & Thompson, 2011). Fountas and Pinnell (2012) claim that teachers’ instructions that effectively introduce the students to potentially challenging features of a new text prior to the actual reading prompt meaning-making practices. These researchers also seem to agree with Stahl (2009) who reported that the introduction to the texts results to statistically significant impacts, particularly regarding comprehension and the acquisition of scientific content. The introductions should be brief and vary according to the readers’ strengths and needs as well as the characteristics of the text. Teachers might discuss the title of the book and provide an overall sense of what the book is about and how it “works” to provide enough support for the students to read the text successfully (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017).

Reading the text. In regards to this component, the students are required to read the text independently within a designated period dependent on its length and complexity (Morgan et al., 2013). The teacher occasionally checks for understanding and requests the non-fluent readers to read quietly under the teacher’s observation and his/her short, focused, appropriately timed interventions (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012) enabling the readers to become problem solvers themselves. The teacher either partly or exclusively guides a student on reading dependent on the student’s needs, but the student can later opt to read independently at his/her own pace if he/she is able to overcome the expected challenges in the reading.

Discussion of the text. After the independent reading, the teacher engages the readers in a discussion pertained to the after reading strategies (Lyons & Thompson, 2011). The after reading discussion session is a significant part of guided reading whose aim is based on the readers’ competency or fluency in reading. Fountas and Pinnell (2012), concurred in their recommendation that after reading discussions helps in establishing opportunities for the readers to summarize content, synthesize, establish links and relate them to their lives and experiences, and help them in expanding their vocabulary in the aim of attaining continued growth in text processing strategies. This step is followed by a response to the text independently to assist the students further develop their comprehension from various perspectives before the teacher finally intervening and revisiting the previous purpose of the reading including how the new understandings could be related and applied to real-life contexts (Morgan et al., 2013).

Teaching points. Here, the teachers have the opportunity to interact with the students to do some teaching for strategic actions. The teaching points must be very specific and focus on some aspect of reading (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). According to Fountas and Pinnell (2017), “the teaching point can be directed toward any of the systems of strategic actions; selection of the point is based on your knowledge of the readers and what they need to learn how to do it” (p. 15). For example, teachers might engage students in “close reading” or call attention to an example of successful problem solving (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017).

Word work. In this component, teachers have a chance to help the students develop a flexible range of strategies for solving words and to use them with ease to develop flexibility and fluency (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). For example, as Fountas and Pinnell (2017) suggested, teachers might ask the students who are just learning how words work to put words that are alike together.

Extending understanding. In this optional component of a guided reading lesson, students reflect on their thinking about the text in any of variety of ways to write about the reading. For example, students can do charts, summarizing, character sketches, lists of interesting words. By doing so, students can extend their understanding of the text (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017).

However, many teachers still experience considerable challenges in implementing guided reading (Firmender, Reis, & Sweeny, 2013; Ford & Opitz, 2008; Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017; Hanke, 2014; Robertson, 2013; Parr & McNaughton, 2014; Saunders-Smith, 2009; Wilson, McNeil, & Gillon, 2015). According to their study, the various concerns by teachers include being unsure of how to conduct guided reading sessions, having difficulties choosing the correct texts, having problems evaluating students’ participation in the guided reading groups, and most importantly, being unsure of how to form and constitute student groups. Thus, it is vital to assess how teachers perceive the formation and constitution of small groups in guided reading sessions.

Grouping in Guided Reading Sessions

According to Fountas & Pinnell (1996), grouping for guided reading sessions is a contentious practice that has remained one of the most thought-provoking features of guided reading processes. This is considering that in every classroom, teachers often encounter a wide range of levels that make it hard to teach general-class lessons or even heterogeneous groupings effectively and if not grouped appropriately, then this means higher likelihoods of getting adverse outcomes (McCallister, 2010; Maine & Hofmann, 2016; Oostdam, Blok, Boendermaker, 2015). For example, there is no guarantee that grouping the students based on their abilities will produce positive results for every student, as argued by Fountas and Pinnell (1996).

Fountas and Pinnell (1996) argued that ability grouping does not improve performance because most students allocated to a group do not advance to an advanced group, the high- and low-grouped learners get varied instruction, and the low-grouped learners’ self-assurance and esteem are adversely affected. Nonetheless, various studies show that grouping learners into smaller groups with heterogeneous grouping may encourage success on several occasions (Hallinan, 2003). However, Fountas and Pinnell (1996; 2017) proposed dynamic grouping, a compromise between heterogeneous and homogenous grouping. Such a grouping strategy was inspired by three key features of a typical classroom: children exhibit a broad range of past awareness, know-how, skills, and intellectual capacity; learners vary in their knowledge and skills; and students learn at different rates (Iaquinta, 2006).

Accordingly, unlike heterogeneous or homogeneous grouping, dynamic groups offer the teachers a better way of grouping the students effectively, hence affording every learner in a group a better opportunity to acquire knowledge (McCallister, 2010). Thus, Fountas and Pinnell (1996) defined dynamic grouping to mean the process through which teachers combine flexible ability grouping with a broad array of heterogeneous grouping within a class setting. Through such a process, teachers get the chance to conduct guided reading sessions in a small group situation where the learners are reading at their level and can move within the groups as abilities change and grow (Iaquinta, 2006). Thus, dynamic grouping allows the learners to read at their respective levels while at the same time preventing the usual adverse impacts evident in typical ability groupings (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). Every teacher should, therefore, strive to form such groups if guided reading instruction is intended to impact the learners in their reading positively.

Underpinning Theories

Like many other initiatives in various fields that have proven hard to implement practically but works well in theory, guided reading is theoretically intended to operate well (Young, 2018). Powell and Kalina (2009), stated that “an effective classroom, where teachers and students are communicating optimally, is dependent on using constructivist strategies, tools, and practices” (p. 241). Constructivism is categorized into a cognitive theory which is primarily attributable to Piaget (Piaget’s Theory) and social constructivism founded by a Russian psychologist, Lev Vygotsky (Vygotsky’s Theory) (Powell & Kalina, 2009). The guided reading strategy is aligned to Vygotsky’s (1978) perception of learning through the creation of an effective and meaningful social instruction setting (Young, 2018).

According to Powell and Kalina (2009), the ideas under Vygotsky’s social constructivism are often constructed socially when a student interacts with colleagues or with the teacher. Such interaction during the discussion periods and the small group sessions are a foundational element of the guided reading approach (Ford & Optiz, 2008; Fountas & Pinnell, 2012). When the students interact with clear ideas from the text, then the discussion, the learning process, and their comprehension abilities become more constructive. Vygotsky, through his learning concept known as the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), argued that with the backing of another person with better capabilities, the learner has an increased chance of doing better than they could individually (Fountas & Pinnell, 2001; Vygotsky, 1978). In fact, Vygotsky (1978) defined ZPD to mean “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86). Simply put, the ZPD is the difference between what a student can accomplish without help and what they can accomplish when adequately guided and encouraged by a more qualified person. Theoretically, it makes sense that a guided student will experience greater accomplishments than an unguided learner based on Vygotsky’s ZPD (Young, 2018).

One of the vital practices that characterize a well-structured guided reading is that a teacher typically opts for an instructional level text (Young, 2018). This, according to Fountas and Pinnell (2001) and Young (2018), means keeping the students in the ZPD since the primary objective of guided reading is to ensure that the learners can productively read and understand a challenging comprehension with the help of their teacher. For a teacher, therefore, teaching in the ZPD means recognizing the learners’ level of development and using the information to modify the instructions somewhat past the development level. Other than offering the necessary instructional activity to advance the development of certain concepts being studied, the teacher also mediates and “scaffolds” the performance of the learners until such a point that they can effectively function independently (Shabani, Khatib, & Ebadi, 2010). This is considering that according to Vygotsky, learning and development are not just a ‘you either know or you don’t’ situation, but an activity where the learner is learning within a ZPD and that once the learner gets appropriate instruction, they will be able to use the learned concept independently and without the need for assistance (Shabani et al., 2010). The guided reading group strategy itself provides the students with the chance to obtain instruction and learn through a scaffolded manner.

Teachers’ Perspective on the Use of Guided Reading

Many scholars and educators have placed the teacher at the center of all guided reading discourses reading (Fisher, 2008; Denton et al., 2014). However, studies exploring guided reading and its impact in the classroom report mixed reactions from those who have participated in guided reading. Through a qualitative study on guided reading using both students’ and teachers’ perspective, Hulan (2010) examined student-led and teacher-led guided reading contexts. Hulan found that student-led discussion groups were more effective when students with a superior understanding of the subject matter led discussions better than those with scant knowledge about the subject. On the other hand, teacher-led discussions revealed that all students irrespective of their cognitive and intelligence levels used diverse reader response strategies. This clearly shows that the teacher takes a central role in successful guided reading discussion groups. However, Hulan’s study did not take into account the influence of the structure, content of the text, and the nature of the intervention by the teacher.

Whitehead and de Jonge’s (2013-14) comparative study in the context of Grade 5 learners in New Zealand using the perspective of teachers outlined the benefits of guided reading to students. The findings of this study indicated the benefits of the strategy in fostering confidence, metacognitive growth, increased understanding, effectiveness, and awareness of various features in texts. However, the study had been small-scale in nature hence could not be generalized to larger populations. Scull (2010) sought teachers’ insights on the benefits of the guided reading approach and identified some as the activation of student’s prior knowledge, enables students to connect the current text with previous understandings, and the facilitation of clearer understanding through thoughtful interactions.

In Swain’s (2010) study, teachers also stressed that guided reading provides a supportive learning and teaching setting. Swain confirmed the potential significance that guided learning has when treated as an integral part of comprehensive reading interventions. The study also revealed that small group instructions assist the teachers of guided teaching in addressing various students’ needs. Swain raised concerns over the integral structures of power within the guided reading approach by believing that these structures instill distrust on the efficacy of the approach, particularly in promoting independent critical thinking. Fletcher, Greenwood, Grimley, Parkhill, and Davis’s (2012) study reinforced Swain’s (2010) belief through their research findings which teachers reported that, irrespective of the pedagogical differences in different grade levels and schools, teachers were found to dominate sideline discussions limiting interactions among learners in guided reading settings.

Through his interviews with teachers, Hanke’s (2014) study indicated that teachers often encountered frustration, especially with the requirement of grouping the learners according to similar needs. The student participants in Hanke’s study actually echoed this sentiment in their perceptions that were depicted in their drawings. Several studies have also examined guided reading within the context of early education and reported unending concerns pertaining to the interpretation of guided reading (Fisher, 2008; Hanke, 2014). Fisher’s (2008) research reported problems within the teacher’s interpretation of guided reading. Through the lens of teachers, Fisher’s research on three classes, indicated challenges in the interpretation of guided reading and the teacher’s reluctance to use guided reading due to lack of clarity on how to implement it in the classroom. Hanke (2014) reported that most teachers were unclear on what they were trying to achieve in the use of guided reading and how to achieve it. In addition to problems related to the quality of discussion within the classrooms as highlighted by Hanke (2014), Fisher (2008) identified the absence of assessment strategies to accompany the strategy and students’ lack of the opportunity to engage collaboratively in discussions as major challenges. Fisher also identified the insufficient understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of the approach among the teachers and the absence of opportunities for meaningful discussions in the sessions that she observed. Ferguson and Wilson’s (2009) research also found that insufficient time and pressures from curriculum expectations and demands greatly impacted the ability of the teachers’ participation the implementation of the approach in class. Some teachers also quoted insufficient resources, especially quality texts as the major contributing factor to the limited use of guided reading.

Some gaps do seem to exist and can actually be identified in past literature relating to the teachers’ perspectives on the use of guided reading. For instance, Denton et al. (2014) claimed that the majority of the previous reading interventions studied show that guided reading settings have precise guidelines. However, the prevalence of limited experimental studies on classroom interventions, which implement the guided reading strategy, is evident when one tries to conduct a search through various databases (Denton et al., 2014; Tobin & Calhoon, 2009).

The ultimate goal of guided reading is to enhance effective independent learning. According to Denton et al. (2014), guided reading is undoubtedly a widely adopted strategy, though its research base is limited. As highlighted in the previous sections of this literature review, research does show several effects of the approach on various tenets of reading, particularly on fluency and comprehension (Oostdam et al., 2015). Some of these empirical studies also have proved that guided reading has either similar impacts or inferior impacts when compared to other small group instruction interventions (Nayak & Sylva, 2013; Tobin & Calhoon, 2009; Walpole, McKenna, Amendum, Pasquarella, & Strong, 2017; Young, 2018). Regardless of the numerous empirical and descriptive studies that focus on guided reading (Fisher, 2008; Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Hanke, 2014; Morgan et al., 2013) and those that study the perspectives of teachers on guided reading (Ferguson & Wilson, 2009; Ford & Opitz, 2008), it is evident that there is a need for more empirical studies to explore the dynamics of guided reading, particularly exploring its impact on reading comprehension from the early grade teachers’ perspectives.

Summary and Integration

From the aforementioned discussions, the effectiveness of guided reading is highly dependent on reading comprehension. In the discussion, reading comprehension is defined as the process by which meaning is constructed from texts, whereby rather than constructing meaning from printed words found directly in paragraphs and essays, meaning is constructed from pieces of information gathered from and scattered across correlating whole sentences within the essay or text (Muliawati, 2017). Challenges in reading and comprehension can be successfully overcome by teaching readers afore-discussed comprehension strategies including the pre-reading, during reading, post-reading, and throughout/general reading strategies. The review of literature also indicates that most teachers are either unaware or not confident in teaching comprehension despite the fact that comprehension is the main reason behind reading aimed at assisting individuals to attain meaning from a particular text and react to the text critically. Children learn how to comprehend by simultaneously engaging in activities and processes that enable them extract and construct meanings by interacting and actively engaging with texts. There is, however, an overall understanding of the importance of implementing various reading strategies. In early grades, reading text more effectively is not the only important aspect of developing reading skills, but ensuring that students gain a good understanding or comprehension of what they are reading is equally important (Fisher, 2008). As discussed, scholars and academic researchers have tried to establish the role of guided reading as a tool for classroom instruction from the teachers’ perspective and outlined several benefits and challenges. However, there are few empirical studies that examine the effects of implementing guided reading on reading comprehension on early grade students using the viewpoint of classroom teachers.

Within reading comprehension spectrum, studies such as that by Nayak and Sylva (2013) have revealed that learners in the guided reading programs outperform their counterparts in other reading comprehension programs. While possible benefits brought forth by guided reading to the students and teachers have been highlighted, possible issues and challenges that could undermine the implementation and success of guided reading or its misinterpretation in the class by teachers have been highlighted. In addition, elements crucial for a guided reading session have been identified to assist teachers reaping the best outcomes from the implementation of the approach.

Guided reading teachers ought to facilitate quality and effective interactions within the class to create opportunities for the students to analyze texts, think critically, negotiate meanings, and solve identified problems by leveraging on their past knowledge to nurture profound comprehension and fluency levels. The success of guided reading has also been identified to be dependent on the availability of the needed resources, time, and knowledge of the selected text. In light of the above findings from past literature, this literature review argues strongly that there is a need to study teachers’ perspectives on the use of guided reading in early grades, particularly pertaining to its influence on reading comprehension. This will greatly assist in identifying plausible interventions that could be effective in promoting successful implementation of the guided reading approach. Chapter 3 outlines this study’s research methodology.

Chapter 3: Methodology

Introduction

This study was to explore teachers’ perspective of implementing guided reading in early grades on reading comprehension. Previous research has shown that teachers in primary school have continuing concerns about the interpretation and implementation of guided reading in early grades. In fact, some teachers were even uncertain about what they were attempting to achieve with guided reading, let alone how they should go about achieving it (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012; Fountas & Pinnell, 2017; Hanke, 2014; Marchard-Martella, Martella, & Lambert, 2015; Shang, 2015). The research questions identified for the present study are: how do elementary school teachers describe their experiences with guided reading strategies? what are teachers’ perspectives of the impact of guided reading on reading comprehension in early grades? how do teachers describe advantages and disadvantages of utilizing guided reading in early grades? This chapter outlines the methodology that will be utilized in a qualitative study using a basic qualitative study (BQS) approach. 15 teachers from public schools were selected to explore their perspectives of implementing guided reading in early grades on reading comprehension. Semi-structured interviews and artifacts in the form of teachers’ lesson plan were considered as data sources in this study. The collected data was analyzed thematically using inductive analysis method.